Having worked with several East African creative initiatives over the past 12 months, Native Instruments highlights the work and sounds of these production outfits, looking at how these pioneering organisations are shaping the area’s contemporary musical narrative.

Electronic music makers from across the African continent are attracting larger and larger international audiences. Yet in the words of one of the East African creatives profiled below, Western-gaze attempts to shorthand the emergence of African electronic music(s) as “the next Cinderella story, the new frontier, the ‘Africa Rising’ narrative,” deserve little credibility.

As the popularity of Gqom, Electro Chaabi, Kwaito, Azonto, Kuduro and Tekno kintueni music have demonstrated, each African electronic scene is irrevocably rooted in its context; every rich tapestry of tone and rhythm is woven through with national, regional and tribal perspectives, collisions of class and politics, and intersections where language, history and musicological tradition meet.

East Africa is no exception, although it has lacked the attention shone on the other points of the compass until recent years. It’s no coincidence then that the most prominent names – Kenyan/Tanzanian initiative Santuri, Uganda’s Nyege Nyege Festival and Femme Electronic music education program, Kenyan DJ/artist crew EA Wave – are at the leading edge of the region’s community-driven music enterprises. The sundowner bars, nightclubs, waterfronts and rave warehouses of Nairobi, Kigali, Kampala, Dar es Salaam, and Jinja are their domain, as they navigate the highs and lows of hybridising glocal sounds, growing communities, and redefining the parameters of success.

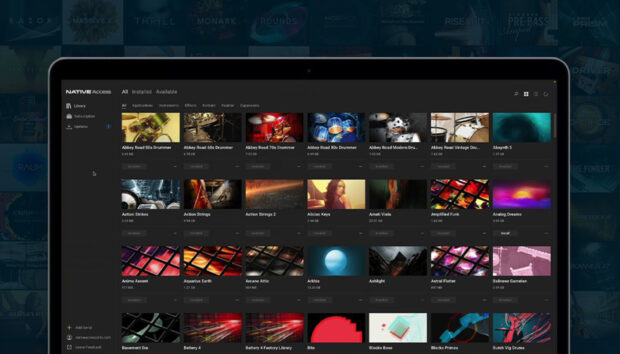

All four of these outfits have partnered with the Native Instruments Outreach project which provides communities, creative platforms, crews and individuals with access to production and performance gear used for training, workshops and events that otherwise might normally be unobtainable due to cost or location. We invited them to share their stories and unique perspectives.

The social engineer

Gregg Mwendwa

Although he is now also a DJ in his own right, Gregg Mwendwa, co-founder of the Santuri platform, prefers to emphasise his behind-the-scenes nature. “I’m just a guy who loves to go to the club and listen to great music,” he offers. “I think I’m just a social innovator, or a social engineer, in not so many words.”

It’s an apt if understated way to describe both his work for Santuri, and his 15 years of experience in development projects throughout East Africa. Many facets of the latter – fostering individual enterprise, community fortification, youth outreach, media and communications strategies – meant that by the time he began taking a personal interest in the electronic music nightlife scene of his hometown Nairobi around 2011, Mwendwa was uniquely placed to apply it through a critical structural lens.

“So much of what I’ve done in development work has been to identify certain gaps, and then work around means and mechanisms to get that gap filled,” he explains. “Something came in my mind like, ‘How about what is happening in East Africa at the moment?’ There is this whole renaissance of electronic music especially from South Africa and West Africa, but then when you come to Kenya or East Africa you find that we we have nothing.” Which isn’t to say that there was no pool of local talent, moreso that Kenyan producers and DJs were taking their musical cues from the south and west. “There was nothing locally homegrown coming out of East Africa that uniquely identified it,” says Mwendwa.

After having identified the absence, what Mwendwa didn’t account for was the mood of resistance he encountered in conversation with Kenyan artists. “Producers told me, ‘I’m already on my path, I can’t go back,’” he says. “With music production especially, once you have that formula then you’re in a safe zone. You just need to churn out hit after hit after hit. These people were pretty much unbothered by the situation, it was just me feeling it.”

Mwendwa eventually found the shared enthusiasm he needed across the border in Tanzania. “I ended up meeting David Tinning by way of Rebecca Corey, who used to manage Sauti za Busara festival,“ he says. “They had also gone through the same problems in Tanzania where the music on radio and in the club and in the buses was all the same, Afropop with a heavy inclination to West Africa. We knew that below the surface there exists rich cultural music textures from across East Africa that had not been exploited or explored by all means.”

Mwendwa and Tinning co-founded Santuri, and set out to organise a music making workshop in Zanzibar alongside the forthcoming edition of Sauti za Busara. “David was on the ground trying to find resources and partners that we could work,” he recalls, “and I was connecting the dots with the artists. With partnerships secured, a pop-up studio constructed and artists bound for Zanzibar, all the elements were finally in place to realise this project. “We were looking for something that had an East African texture, but crossed with more exposed electronic music. A global touch with ethno and folk instrumentalists.”

However after those first sessions wrapped, the recordings fell short of the aim. “The sound that came out ended up sounding like it could come from everywhere else, but not East Africa,” says Mwendwa, “I mean we had a Nigerian musician, we had another guy from Madagascar. It didn’t have that touch of East Africa.” After going back to the drawing board, a second workshop recording session was planned in Uganda. This second pass was a home run. “We invited more local instrumentalists, especially on stringed instruments and percussion. This is what we looking for.”

Santuri has since grown into a multifaceted platform that comprises of music releases, community workshops, studio services, the Santuri Sample Bank resource, events, and a partnership with Uganda’s DJ Rachael on her Femme Electronic program. Still, given his proclivity towards discovering further opportunities, Mwendwa is is keen to widen the scope of Santuri to include further uncharted territory. “We were like that matchstick that was waiting for the fuel or lighter,” he says. “We’ve been able to bridge this gap. So what next?”

Riding the crest of ‘Nu Nairobi’

EA Wave

There is much within the dynamic of speaking of Jacob Solomon, aka DJ/producer Jinku, that contains the universal hallmarks of interviewing a twenty-something DJ whose career is on a serious uptick. When we connect over Skype, his Nairobi morning finds him arriving home on zero sleep after an all-night gig. He eats cereal as we talk, and will presumably sleep off a good part of the day afterwards, as per the DJ’s nocturnal lifestyle.

Yet while his story of discovering electronic music, learning to DJ, finding local like-minds online and forming a real life production and DJ crew – EA Wave – is not unusual, some of the feedback EA Wave receive is. “We had one fan who was surprised that we are black, like ‘just black kids’,” he recalls. “Like, c’mon. Really?”

“The thing is,” he continues, “we are not in a bubble. We have internet and listen to artists from outside Africa. The fact that’s in our music is because we are connected.” EA Wave’s sound has earned comparisons to Bonobo and Four Tet, yet bundled in with their borderless sound is a willingness to challenge preconceptions of what EA (=East African) music ought to be. “Does it have to be African vocals and percussion and things like that?” he asks. “I come from the school of, if I make that music, and I’m African, then by virtue the music should be African.”

This fresh take on the boundaries between music and identity exemplifies the umbrella term for the sounds coming out of EA Wave’s home base: ‘Nu Nairobi’. “I think having that name is what made everything start falling into place,” says Solomon, “there’s now a much bigger variety of events in Nairobi, like now you have reggae, live music, acoustic musicians, electronic DJs, very many producers. It’s a scene now.” He also credits one Nairobi venue in particular as an instrumental force in cultivating these budding communities. “The Alchemist was the first venue that booked us and allowed us to do what we do,” he says, “It’s a venue that is synonymous with alternative music. It has a studio behind, a tattoo parlour, a comic book and record shop, food trucks, different restaurants. When you have all those spaces bringing in new people then you help them listen to alternative music and see what’s happening in the scene. It’s just really helped a lot.”

Another crucial meeting spot is Creatives Garage, a multi-disciplinary arts space that offered the crew free studio time soon after they decided to create a production and DJ team together. The weekly sessions bled into their #WaveyWednesdays project, wherein one new production is uploaded to their Soundcloud page each week, featuring every possible constellation of its six core members and guests. #WaveyWednesdays showcases the complete EA Wave sound palette that Solomon describes as “fucking broad.”

“We are six people,” he explains. “I’m more driven by African percussion and instrumentation, then you have Sichangi who does future bass, and Ukweli who does afrobeat and R&B. Nu fvnk does boom-bap hip hop, then you have Hiribae who does jazz instrumentation and trap, Mvroe who does trap. It’s crazy when we collaborate with each other. We bring all of that so it becomes like a fusion of each other’s sound.”

Alongside each individual’s personal projects, collaborations, and a rash of EPs and albums due for release through the rest of 2018, EA Wave live is also on the cards. “We’re building a really wicked live set, it’s sounding really good,” says Solomon, “once we’re done with that we want to translate our set into an EA Wave EP or album.” Further into the future, EA Wave’s spirit of Afro-centred collaboration continues for Solomon into fantasy league territory, “Baaba Maal. Or Youssou N’Dour. Or Femi Kuti,” he says, listing his dream collaborators. “They do world music. I hate the term ‘World Music’. African powerhouses. The only times you hear them in electronic music is in songs have been remixed, but making a song from scratch…. Yeah. That would be fucking mental.”

Not just a festival, not just a destination

Nyege Nyege festival

When I spoke with Nyege Nyege’s co-founders, Arlen Dilsizian and Derek Debru, they were in the middle of a very busy period which sounded like it wouldn’t be letting up anytime soon. The lineup for the 2018 edition of their festival was in the process of being finalised, they had just announced a three-year sponsorship deal with major telecommunications carrier MTN Uganda, and after being kicked out of their studio space they were in the process of moving to another location in their base city Jinja, Uganda.

Dilsizian describes the festival’s setting, the Nile Discovery Beach Resort in Jinja as, “A not-quite abandoned resort that never kind of happened, that’s kind of semi-built. Surrounded by acres of jungle. With its own beach and folies and wavering pathways. It’s a beautiful site.” This year will mark the third edition of a festival which has gathered word-of-mouth praise and worldwide press inches at a dizzying rate, but Nyege Nyege’s founders are keen to distance it from the wanderlusting ‘destination festival’ category. After all, In the same spirit of their totemic half-finished festival location, Nyege Nyege’s branching multidisciplinary project has also taken root and unexpectedly bloomed out of the rubble of other failed plans.

Dilsizian is of Armenian heritage and Greek upbringing, and he arrived in Uganda eight years ago to take a lectureship position at the Kampala Film School. The flaws of Uganda’s public institutions soon became apparent to the academic. “Higher education in Uganda is a very sad story,” he says, “because most of these institutions have been hollowed out over the last 20 years with the lost decade of the 1980s and structural adjustment. I don’t think any of these the institutions have really recovered to their former glory.”

The frustrations of the bureaucratic process – like remaining unpaid by the school for one year – engendered a kind of guerilla style self sufficiency when Dilsizian and Debru, a Belgian film and and music buff, met at the film school, and the initial concept for Nyege Nyege began to take shape. “It was just us and the community around us,” says Dilsizian, “and it all developed really organically. We never really decided to do any of the things that we do, they kind of just happened. We started doing parties and then the festival came off the crazy whim of an idea that was developed in four weeks before the event. We lost $40,000, 800 people showed up, it rained for three days. Everyone loved it.”

Everyone continues to love it. Nyege Nyege currently encompasses film projects, studio production and music archiving, however as migrants to Uganda its founders are thoughtful about defining the cultural heart and messaging of the most visible part of the project – the festival. “It’s sometimes paradoxical here,” says Debru. “Some Ugandans are like, ‘We don’t want Ugandan musicians to come, we only want international musicians.’ Others are like, ‘No, we can’t lose our culture.’ I would say for a certain type of middle class Ugandan they are excited about foreigners and not so excited about us making it more inclusive. So we’re trying to find that middle ground.”

Much in the same way that the idea of Santuri was sparked from the desire to encourage more local and regional music experimentation, Nyege Nyege’s founders also aim to provide a counterpoint to the ubiquitous presence of mainstream music from other African regions. “It’s more about building the local market in terms of fighting off the mainstream and creating new niches that develop over time,” explains Debru. “Mainstream music and radio and TV are still controlling 90% of what’s being made and heard here. That really affects the economics of music and the potential opportunities that come with being involved with the arts. For example the artists that we promote that are going international. They’re not known here. It’s not for lack of trying. There’s two projects happening here, one is to showcase what is happening here to the rest of the world, because we fear that there’s a big interest in it and that ‘new frontier’ element, and then the other part is to create some dents into the local industry here and encourage more people to take up DJing, to do sort of outsider productions and get interested in their own roots and own traditional cultures.”

The 20-year overnight sensation

DJ Rachael

While Uganda’s highest profile DJ, DJ Racheal, is clearly linked to all of the people referenced above (she’s co-produced a track with EA Wave members, she runs the Femme Electronic programme in partnership with Santuri, and has been a lynchpin of all Nyege Nyege Festival lineups), she also represents the potential outcomes of individual tenacity.

2017 was Rachael Kungu’s celebrated breakout year; she featured alongside The Black Madonna in the Smirnoff sponsored film Equalizing Music, she travelled to TBM’s native Chicago on invitation to DJ at Smart Bar, she began to earn international recognition for her Femme Electronic initiative, she presented a TED talk, and traveled to Europe to play a set of gigs. Yet this was all the result of two decades as a stalwart figure of Kampala’s nightlife, and not without challenges.

Displaying a proclivity for music in childhood, Rachael’s upbringing in the Kamocha district was limited to what was freely available to her: watching music videos, and participating in school musical productions. With no active encouragement from family or teachers to pursue studying music, her first true outlet became freestyle rapping. “One time I went to this club with a friend of mine and my uncle,” Kungu recalls, “and I told them to give me the microphone so I could rhyme to some songs. They liked it. I was still in school, but it was during the holidays. They encouraged me to stay on and every night I would come in.”

Rapping neatly dovetailed into DJing, and the same nightclub also served as an incubator for her mixing and programming style for two years. She was poached by another club which offered a more harmonious fit with her freewheeling blends of house music, Afropop, traditional music, hip hop and R&B. During her residency which lasted eight years, Kungu realised her true focus was DJing, and she developed into one of Kampala’s most revered selectors. “Then when I was still high up there,” she recalls, “they laid me off. I heard a story that there was a DJ who took competition too far. They influenced the boss, made me leave the club. So I left and I went on an adventure of my own.”

The severing of her residency in the mid-2000s turned out to be a blessed curse; as a freelance DJ without a home club, and being a rarely-encountered female DJ on the circuit allowed Rachael to catapult herself further ahead, while many other freelance DJs were tied to the all-male mobile disco DJ circuit. “The good thing is that I had developed my name at this club I left,” she says, “so people sought after me. I had gigs and corporate events and festivals, bars and private parties. I would go to Nairobi, Dar Es Salaam, Kigali. Of course there was a lull within some of those years but people sought me out and kept me going.”

With her independent career thriving, Kungu began to examine the absence of female peers on the circuit she trafficked. “There were no girls DJs coming up,” she says. “I would see the odd female somewhere, you’d see them play one time then you wouldn’t hear about them anymore. I was wondering, ‘What is going on?’ I developed this idea to teach girls how to DJ. I didn’t start on it straight away, It was a thought.”

Around 2015, with the support of Santuri, Kungu took her idea the head of the Goethe Institute in Kampala as a proposal. “I developed the name Femme Electronic as a project that teaches girls how to DJ and produce music,” she says, “but of course it can be extended into other other sectors within the creative industries.” The first free entry one-day workshop was held in Kungu’s home, as have the subsequent workshops which convene roughly every month – or as close to that as her more-packed-than-ever packed schedule will allow.

Nyege Nyege and Kampire photos: Darlyne Komukama

Gregg Mwendwa, EA Wave and DJ Rachael photos: Jude Clark

Additional festival photos courtesy of Nyege Nyege Festival