Award-winning film and television composer Jacob Yoffee explains how he got started in scoring, plus gives a full rundown of the KOMPLETE instruments and effects at the heart of his Los Angeles studio.

Born in North Carolina, concert and film composer Jacob Yoffee studied piano and saxophone from a young age, and majored in classical composition at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Maryland. It was here that Yoffee ventured into the world of modern jazz, which would become the perfect schooling for a residency at New York University to study film score programming.

Yoffee relocated to Los Angeles for his first film score assignment, Dimension Films’ Children of the Corn reboot. This was later followed by TV series projects for Blue, The PET Squad files, and Finding Carter, and trailer music for huge movie franchises including Star Wars, The Hobbit and X-Men. As a feature film composer, Yoffee has scored over twenty movies. He is currently working on Disney Channel’s American sitcom, Andy Mack.

Music School

I knew when I was eight-years old that I was really interested in film music because I always loved orchestral music. The power of music and the moving image was just so enticing. Many people are turned off by a dissonant orchestral texture. If you match it up perfectly to a horror film, people will enjoy it and won’t be fazed at all, but once you take away the image, suddenly the music’s not palatable. I always thought it was really cool that when you watched Star Wars you’re listening to a big orchestral symphonic work that most people wouldn’t pay to listen to, but when you match it to the right image people get it.

Studying at New York University

Studying the first year was like composer boot camp. I remember going into my first private lesson and my mentor saying, ‘this isn’t going to work at all, and that I was way too much of a jazz musician – the way I dressed was too casual, and no one was going to trust me with a large contract for a film. I was not only learning how I could handle a feature film score technically and logistically, but the social etiquette of the film industry in general.

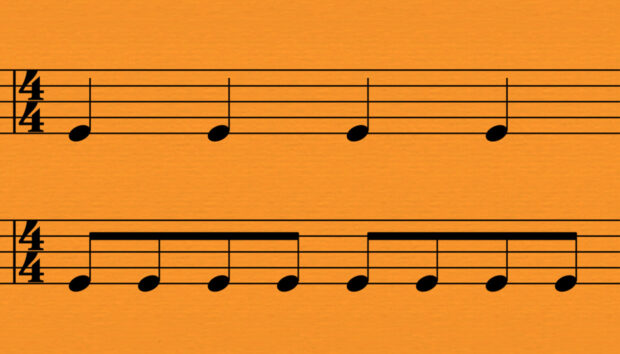

One of the most difficult transitions for me was that I’d come from the conservatory world where everything was done by hand. When I composed, I would sit at a piano with score paper and pencil and write the ‘old-fashioned’ way. I’d never worked with sequencers in any real sense or on music production, and wasn’t familiar with Pro Tools.

It was quite painful learning how to compose within Logic, and be creative within a computer environment without writing anything down. You can get projects where you’re allowed more time, but for a television series I might only have 20 minutes to write and prepare a cue that needs to be emailed off. I was working in the computer to create the music and using the MIDI information to transfer it into Finale or Sibelius to prepare parts to record the orchestra. Then I would bring that audio information back into my DAW to mix.

First Assignment

My first real assignment was the Children of the Corn sequel for the Weinstein Company. There was no way in hell I was going to drop the ball on that project. I spent almost a month on it and would usually do three composing shifts a day. At that point, I was well on my way with sample libraries and all the equipment, but was still balancing how to work with samples and the few musicians I was hiring to record live. I was trying to mix those two things and send music to the music supervisor and director to get it approved. It was definitely like ripping the band aid off – I think I had to write something like 90 minutes of music.

Writing for film trailers

Writing for trailers has changed, and I consider it the Olympics of film scoring because you can spend months working on them. A lot of the larger trailer music houses will record albums of trailer music with 20-40 tracks, and release them several times a year. They’ll be licensed, so the stems will be sent to the trailer house by request and get chopped up. There may be some customisation, but largely the track is what was already recorded. The other side is where they call you in and say they need a track that is custom-designed for them. You may or may not get to see the trailer, and you go back and forth as many times as it takes until it’s ‘finished’ and the client is happy.

I was called in early November to score the latest Pirates of the Caribbean trailer, but we didn’t finish it until it was released at the end of March. When it comes down to it, it’s about marketing – and they care a lot. Every note and second is analysed and judged. You have to make sure that it sounds huge, exciting, current and fresh. So it’s quite intense and stressful in a lot of ways, but super-exciting too… and the pay is great because it comes out of the advertising budget.

Directors do get involved in the trailer, but I don’t ever meet them. If there are music notes, you get them through several degrees of separation. You might get notes back saying they want the music to be less intense and more magical, or less orchestral and more hybrid-sounding. I remember one comment saying: “Can we up the percentage of emotion?”

Writing for trailers is the Olympics of film scoring

Kompleting the package

I consider Logic to be the workstation; that’s where I do all my creative stuff. I use Pro Tools to prepare my deliveries to the mix stage, because when I’m delivering the stems and the final music for any project, it’s always best to bring everything in, synch it up and have it prepared in a session so they can just import the data into their workstation.

When I first started, I used the East West/Quantum Leap Symphonic Orchestra, and Omnisphere by Spectrasonics. Everyone kept saying I needed to use Massive, Reaktor, and FM8 because they were fantastic for sci-fi projects, and I could design my own sounds really quickly.

KONTAKT

Kontakt is great in my setup, because I have quite large templates. The Pirates trailer had well over 300 individual tracks and instruments, and KONTAKT is able to handle all of that without any slowdown in my DAW. I like to work remotely with musicians who can record themselves. I have a guitarist, drummer, bass player and someone for horns on retainer. They can record stuff and send me tracks, but obviously need to know what to record. With Komplete 11 Ultimate, I can use the MIDI to play in what I want them to do, and give a little representation of what it’s going to sound like. For example, I’ll use a guitar effect to give the guitarist an idea of what I’m going for and then I can bounce out the audio stems and send them to him so he can email me back audio tracks.

When it comes down to it, everybody’s really keen on getting original sounds; you want to move away from using presets as soon as you can. What I love about the Native Instruments stuff is that it’s so easily tweaked that you can really bend sounds to what you need them to be.

BATTERY

I’ve used Battery quite a bit and really like it because you can sculpt every single sound that you have in there, in addition to importing your own samples. For instance, I did the score for a feature-length documentary about painkiller addiction called Dr. Feelgood: Dealer or Healer? and had an idea where all the drum sounds you heard were sampled from prescription pill bottles. So I’d take the pills and pour them onto a desk and the sound of them hitting the desk would be a splash cymbal or a hi-hat. Or, if I hit the bottle with my open palm, that would be the kick drum. I’d just pitch them down, make different morphs and distortions, and bring all of that into BATTERY so I could assign the sounds and play them like a kit on my keyboard.

Effects and hardware

For effects, I have an Apollo Interface, and use some UAD plugins. I use a ton of the Native Instruments effects, especially when it comes to distortion, guitars and the pop cues that I need to do. I’ll use the EQ and compressors and mix and match between all of the effects I have, because with every project you want a little bit of a different sound. I also have an iPad and use a Touch OSC graphic interface that is IO-designed to work with some of the Spitfire Audio libraries to control vibrato and volume for a lot of the orchestral patches.

I’ve got two synths, the DSI Prophet 12 and a Roland Fantom-X, and a Doepfer piano MIDI controller. I worked entirely in the box for a long time, but also wanted to touch and turn knobs to get as near to the real analogue sound as possible. I use the Prophet 12 a lot, because you come across some really happy accidents that way. When you blend a real instrument with soft synths it gives everything more credibility, and I’ll run all the outboard gear through a BigSky Strymon Pedal to get great reverb washes.

But for me, every project comes down to time. When I’m working with hardware, it just takes longer. It’s slower and you’ve got to work on recording and getting the right sound tweaked properly, but there’s so much control with soft synths. I can recall old sessions and everything sounds exactly the same as I left it, so I end up using the soft synths more as a result.

How to get into the film industry

I would say that whatever kind of music you envision writing for film, you need to produce those tracks now. It’s a cart-before-the-horse situation; you’re not going to get hired to do something until you can already prove you can do that kind of music. If you want to do orchestral music, get some synth libraries and start writing, or save some money and record live. If you want to do electronic music, write stuff that’s similar to what you’re hearing in films and build a portfolio.

There are people that don’t read music. I think Hans Zimmer has got to be one of the most famous examples. As far as I understand, he doesn’t read music and is doing quite well. There’s Trent Reznor too. So there are definitely people doing it without understanding musical notation. Everyone comes into the industry with different strengths and weakness, and I think there’s room for every type of musician.

photo credits: Priscilla Jimenez