Jlin is one of electronic music’s most unique voices. The Indiana-based producer’s explosive debut album Dark Energy is a tense affair that challenges listeners and defies easy categorization. The album received unanimous praise in the music press, earning top spots on album of the year lists from The Quietus and The Wire. Opening up about her intuition, production setups, and the creative processes that lead to her distinctive sound, the Komplete Sketches artist discusses her philosophies on music-making, and building a collection of gear.

What is your production setup?

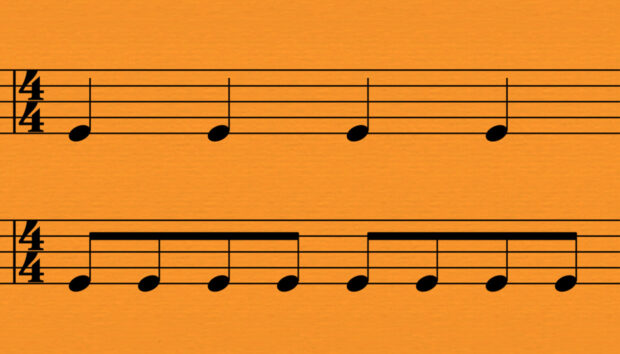

My production setup changes constantly. I usually take stuff away, not add to it. Most people would think the opposite. I own a Maschine MK2, which was my first bit of music equipment, and also an AKAI MPC Studio controller. I’ve also got some low-budget JBL speakers. Here’s the funny part: most people think, “The more expensive, the better,” but these speakers—which I use to mixdown my tracks—only cost 139 U.S. dollars a pair. I’m definitely a “whatever works” kind of person. My main DAW is FL Studio—a friend introduced me to it when I was first starting out. But sometimes I use REASON as well. There’s no set way that I do anything. When I first started out around 2007, I thought I wanted to make footwork tracks. That’s what I intended to do. But after a while, my music turned into something very different. I wasn’t getting the sound that I wanted, so I had a love-hate relationship with FL Studio at the start. But ultimately I loved the challenge. Every day I was stepping a little closer to what I thought I wanted to do. By early 2010, I had really gotten somewhere; I’d developed a lot of my skills by that point.

How did you get into using Native Instruments gear?

My first introduction was through Razor. And it’s crazy because I recently met the guy who made it, Errorsmith. I was playing CTM Festival this year, and as soon as I walked into Berghain, I got lost and couldn’t find the backstage area. He was the first person I ran into, and he helped me find where I was supposed to go. I was so excited to meet him in person because I love RAZOR. It turns out he had been following my work for the last three years and was a big fan. Honestly, outside of RAZOR and Massive, I wasn’t receptive to other synths at all, so meeting him was a BIG deal. I met RAZOR!

How do you usually start a track?

It completely depends on my mood. Everything I do starts out as a blank sheet of paper. I’m very abstract in that respect; there’s no blueprint. When people ask me what my method is, I’m like, “What method?” I think if you always take the same approach it becomes stagnant after a while. You can depend on that approach too much and it makes you less innovative. Having no set method definitely makes the whole process more challenging and ultimately more rewarding for me.

Does the final version of your track always resemble the first sketch? Or is it unrecognizable by the time you’re finished?

Sometimes the final version may end up sounding similar to my first draft. But most times the track is completely unrecognizable by the time it’s finished. The only thing I might keep from an initial idea would be a set of hi-hats or something like that.

How do you know when the track is finished?

I would say it comes down to experience. When it’s done, there is just a sense. It’s almost like your body aligning with your spirit; your physical aligning with your spiritual.

Do you ask for feedback from other producers or friends when you’re working on something?

My mom and also my best friend give me feedback and are very honest. My mom usually bothers me when I’m in the middle of the track. She’s on pins and needles until I walk into her room and tell her I’m done. She’s always the first to listen to all of my tracks. She comes in my room and sits on the end of my bed and I play the track to her.

You mentioned that you don’t play any traditional instrument proficiently. Do you find that your lack of music training liberates you while making music? Or would you like to know more about things like music theory?

For me, music theory is more of a hindrance. At one point I was trying to learn how to finger drum, so I decided to take piano lessons to strengthen my fingers. I actually had a professional piano player who studied at Juilliard, a prestigious music school in New York, tell me that she could not teach me. I wanted her to show me some basic things on the piano and played her some of my music. After hearing some tracks, she said there was no point in teaching me because I already had everything I need. Then she recommended another teacher to me who had mentored under her. I went to his house, played him some of my music once again, and after some sessions he said the same thing: he couldn’t teach me because he would be undoing what I already know. He said my innovation might be undone by learning this instrument. So I got turned down twice and realized that I’m never going to learn how to finger drum.

Do you think it helps to have a lot of gear at your disposal?

Not at all. It’s not about the music equipment; it’s about you. You can have the best of the best gear, but your production can still be poor. I say to people who have absolutely nothing, “Make it sound like you just came out of a grade-A studio.” Everything comes through you, the person. I’ve heard guys working with buckets and sticks make better-sounding drums than some fancy drum set.

For me, music theory is more of a hindrance

Do you think it helps to gain knowledge from watching hours of YouTube music production tutorials?

Watching too many tutorials reduces your creativity, your imagination and your innovation. That’s why we have—and I hate to say it—so many imitations now. It’s okay to say about an artist, “I like his or her sound.” But like my mom said to me when I first started making music: “What do you sound like?” A lot of people don’t want to do that because that means you have to step out of your comfort zone. I would say that the main aspect of finding your sound is 98 percent non-music-related, but about actually figuring out who you are as a person.

Is there a moment when you usually get stuck while making a track? How do you deal with that?

I usually just start hating everybody around me when that happens. I hate them until something comes along, and then I’m fine again. Usually when I get stuck, I just stop. If I don’t hear it, it means I’m not supposed to hear it right now. But when you’re a creative person, it’s hard to step away and take breaks. Taking breaks is essential, though, because your mind needs to rest, your heart needs to rest—all your senses need to rest. Taking a break does not mean that you’ve given up. I was in a rut when I came back from playing in Europe recently. I couldn’t focus; it was terrible. You have those days. We all have some vice that affects our creativity. There are definitely times when I ask myself, “Why on earth am I doing this thing that causes me so much anxiety—on purpose?” On the track “Black Origami”, I experienced that in a big way. The track was basically done; I just needed an ending, so basically the last 24 bars had to be done. It took me three days to get through those last 24 bars.

Where is your studio?

My studio is at home in my bedroom. To me, studio means, “Roll out of bed and get to work.”

You’ve quit your day job now, right?

Yes. Until recently I was working in a steel mill doing 12-to-16 hour shifts a day. Physically, it was extremely taxing on my body. I’d basically work for four days straight and then have three or four days off. But on my days off it would take me at least a day and a half to recuperate before I could start making music again. And God forbid I would be in a creative rut during that time. Then I’d feel like my time was being wasted. Some people tell me that my music sounds very industrial—perhaps that’s because of the steel mill. But honestly, I don’t hear it. For me, music was an escape from that place. Now that I’ve quit that job, I’ve found that my music has actually turned a sharp left from where it was before. It’s really moving in another direction compared to my last album. That’s important to me: to keep moving. I could easily make another album that sounds like Dark Energy, but I don’t want to do that. I’m over that album now. It’s time to move on.

Do you enjoy collaborating?

Honestly, not so much. But there have been collaborations, like the one with Holly Herndon for my track ‘Expand’ on Dark Energy, which felt very in sync. We were having the time of our lives working on that. Holly had heard my track ‘Erotic Heat’ and wrote to me saying how much she loved it. After that, we just kept talking, and it escalated into us collaborating on my track ‘Expand’. When we released it, it totally blew up and we ended up being featured in the New York Times. We’re both really proud of each other.

Is there anything you learned inside the studio that you can apply to life outside the studio?

Yes. Take simplicity and make it complex.

Your music is played in clubs. Do you enjoy clubbing yourself?

I hate it. In fact, when I turned 21, I ditched my own party at a club so I could watch a National Geographic documentary about the wooly mammoth. It was a two-hour special, and there was no way I was going to miss that. I also really like the History Channel, but it’s not as good as it used to be.

This article was originally published at Electronic Beats.