TesseracT sits at the frontier of the djent movement, a sub-genre of progressive metal that incorporates atypical rhythm structures, polyphonic grooves and leftfield conceptual arrangements. Guitarist Acle Kahney and co-producer Aidan O’Brien are central to the band’s disorientating sound; dissected and reassembled using a range of Native Instruments tools.

When nu-metal arrived in the mid-‘90s, the likes of Korn and Linkin Park introduced elements of grunge, hip hop and alternative rock and integrated electronic music technology into the production process. The English five-piece band TesseracT have evolved the genre further still, dragging it kicking and screaming into the 21st century. The forward-thinking collective ripped up the rulebook on their debut album, One, particularly on tracks such as the 27-minute ‘Concealing Fate’ – a conceptual six-part apocalypse of divergent sounds and styles.

A decade later and the band are still busy modelling metal’s conceptual borders, toying with a mixture of harsh and clean vocals, dense melodic passages and subtle backgrounds, influenced by polar opposite tones and atmospheres more readily found in ambient music. Modern technology has become a huge driver of TesseracT‘s production process, with Native Instruments enabling a seamless interplay of sounds from which to cultivate a sonic multi-dimensionality that the metal genre has rarely conceived of until now.

Were you influenced by the early metal bands like Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath or nu-metal artists like Korn or Slipknot?

Acle: I was brought up on Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and The Doors, but in terms of modern metal music, Meshuggah has been a big influence. Other members of the band are more into the likes of Pantera and Slayer, but we also like listening to music that isn’t metal, like Jeff Buckley and an electronic guy called Lorn.

Aidan: I’m in a weird position because I’m not really much of a metal fan. I work with TesseracT as a writer, producer and sound engineer. I knew a couple of the guys and got pulled into the whole metal world. That means my influences are not very metal-based, but more electronic and ambient. But I still love what TesseracT does.

Were there certain generic tropes that you deliberately wanted to avoid?

Acle: Early on, I hated things like blast beats – I’ve never been a fan of those constant snare drums. We’ve always tried to avoid cheese metal, and I suppose we’ve always tried to keep the groove element pretty strong. The new album, Sonder, is a mixture of what we’ve previously released but with lighter, more ambient touches. It’s a lot more melodic and dynamic too. We’ve touched on that in the past, but now it doesn’t feel so forced, so we’ve been able to go to town on that element of the production.

Are the ambient moments employed to add emotional complexity or as a tool to give those louder periods more impact?

Aidan: Quiet verses followed by loud choruses are an easy trick I suppose. There’s that phrase that says ‘sound is only as loud as the silence that proceeds it’. It’s good to play around with that because if someone is listening to something from a neutral point of view, then when a riff follows something that’s ambient, calming and soft, it’s going to have a bigger impact. That can be tricky though; we wanted to try to bleed those elements together with the electronic elements in the background.

You worked in several studios; 4D Sounds, Celestial Sounds and Project Studios. What was that dictated by?

Acle: Essentially, 4D Sounds is my home studio. A lot of the instrumentation was done there and we tracked all the guitars and did all the mixing and mastering there too. Celestial Sounds is Dan Tomkin’s studio, where he tracked all the vocals.

Aidan: I also have a home setup, but the whole album was pretty much done remotely. The band was very rarely in the same room over the course of its creation. I’d work on something, send it to Acle to rework it and Dan would add vocal ideas. We’d bounce files online from our separate studios, so the production was collaborative, but the mixing was all done by Acle.

Does the writing process start in the traditional way, with guitar riffs etc., or in the box?

Acle: It’s hard to pin down. Sometimes I might have a riff and add drums to that, or I might work backwards. Other times, Aidan will bring melody or song ideas, so it’s quite a varied process.

Aidan: Recording this album was quite different. It’s fair to say that in the past it’s been Acle who’s written all the initial ideas, but we opened it right up with this album with the whole band throwing around riffs and song structures and swapping around chord progressions, melodies and grooves. None of it was done in a traditional way, like a band jamming in a room.

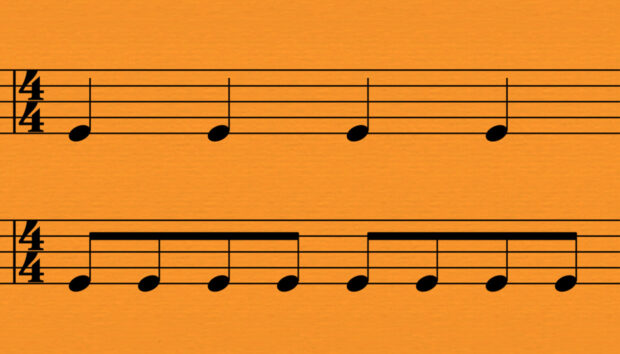

Typically, we’d imagine a metal band uses live drums, how do you tend to process them?

Acle: Due to time constraints and deadlines, all the drums on Sonder were programmed. Basically, we didn’t really have time to learn the songs and go into the studio and track them a way that would do them justice. We used a combination of Toontrack’s Drumkits From Hell and some samples that, together with drummer Jay Postones, were made at Middle Farm Studios in Devon.

Are there certain techniques you need to employ to create a very natural sounding drum kit?

Acle: We tried not to make them sound programmed. Implementing as many room mics as you possibly can usually lend an element of realness to it. You can also add little touches of realism using ghost notes. We’ll typically use Kontakt for drum sampling. The samples were taken from Jay’s kit a while ago and I made my own instrument NKI patches and used Kontakt’s KSP scripting. It took a while to learn all the round-robins and make all the kicks, snares and drums, but we used those techniques quite a lot on the third album Polaris and Sonder.

What first alerted you to Native Instruments products and how they could be beneficial to your production process?

Acle: Probably about 10 years ago. The first thing I used was Absynth; either version two or three. That was my first entry-level synth, and I thought it had some very cool sounds. It wasn’t long before I was playing with and implementing them into the TesseracT demos. I also used the first ever Drumkit From Hell, which was based on Native Instruments Battery, but nowadays we mainly use Kontakt because we love all the libraries you can get for it.

Aidan: I also started out using Absynth; then I got involved with Kontakt because it’s completely ubiquitous if you want to use any reputable sample library. Going through and learning more about programming in Kontakt, it’s been an awesome tool for creating a lot of my own ambient instruments. Just before I started this album, I got the Komplete Ultimate 11 bundle, so I had a whole new array of toys to play with, which has been amazing. I’ve gone back to Absynth as a sound design tool, learned Massive from the ground up, and I’m using Battery in quite a non-traditional way – not as a drum instrument as such. I love loading in a whole song and cutting it up using different instances of the same song via different triggers, chopping them up in interesting ways and programming choppy film sample rhythms and quartet-type stuff. All of that is central to how I write.

You mentioned that you’d don’t come from a metal background, so do you tend to find Native Instruments fits a multitude of genres?

Aidan: I think so. The lines between genres are becoming increasingly blurred. If you’re trying to create something that sounds like Pantera, software might not be as straight-up useful, because you’d want everything to sound as if it was created in one room. But in terms of modern music, Native Instruments has such an amazing set of tools that you can use in all kinds of interesting ways. Even if you’re not making electronic music per se, you can use Massive to layer bass parts to fill out the low end and get a decent sub bass or as a mixing tool rather than what you might expect to get from a soft synth. That’s the great thing about using Native Instruments stuff, you get a complete arsenal of tools and you’ll always be able to find an interesting way to use them for any kind of music.

What about GUITAR RIG? You wouldn’t imagine a metal band would need to use software for that element of the production?

Aidan: Funnily enough, I use Guitar Rig all the time, but I don’t think I’ve ever used it on a guitar. I do very little guitar recording, but I love it as a sound design tool, usually playing preset roulette and putting a piano or electric piano sound through it. It’s an incredibly versatile tool.

You’re a guitar player Acle, so will you use pedals for effects, turn to software or use a combination of both?

Acle: Some of the guitar melodies were intertwined with the amazing synth sounds that Aidan makes, but for the latest album, Sonder, the guitar effects were all running through Kemper amps. We did use a few plugins for delay and reverb, mostly Soundtoys’ EchoBoy and the Valhalla Shimmer DSP.

Aidan, I know you used some of the more exotic NI software like Una Corda and The Giant?

Aidan: I used Native Instruments’ Una Corda, which is the Nils Frahm piano sample library where each piano only has one string per note. Usually, you’ll have three or four strings per note, which all have to be in tune, but the Una Corda makes for this really amazing stubbed piano sound. It’s awesome because Nils Frahm and Olafur Arnald’s piano sounds have been so popular over the last few years, so it’s great to find a sample library that’s completely aimed at playing the instrument as softly as possible. The Una Cordea was pretty much our go-to piano sound on the album. I love how you can mix in all the different levels of imperfection, whether it’s the piano player in the room or the thump of the keys or pedals, and you can cite exactly how much of that you can let through. Nobody would have any idea that you’re not listening to a real recorded piano. The Giant, again, is a really versatile piano. You can get soft sounds out of it, big, heavy, clangy piano sounds or bright pop sounds.

Do you use DAMAGE for adding distortion, or do you not need too much processing considering you’re also using traditional instruments?

Aidan: Damage really interests me. We created a lot of programmed sounds and tried to use more cinematic percussion because we found that to be a very interesting mix. When I’m arranging stuff, I have to try to remember that I’m producing for a metal band, so I don’t want to do anything that will take over or create a whole new sound world. Damage is really good for that because it doesn’t necessarily sound like some big Hans Zimmer percussion section; you can vary it and make it sound really electronic.

I understand you turned to social media to get some of the more gritty samples?

Aidan: We used Facebook to ask people from around the world to submit field recordings. The idea was to get recordings from everyday life and weave them into the album in different ways, so we’d use Damage to create these unimaginable sounds. At one point, someone sent in a recording of a power drill, which is really unmusical, but by stretching it out, treating it and dragging it into Kontakt, we could map it out across a keyboard and create this weird ambient pad.

Acle, you do the mastering too, which is quite rare to find in any band?

Acle: Well I’ve got quite a lot of outboard gear in the studio, lots of EQs and compressors. About halfway through the mixing process, I’ll start to tinker with the mastering side of things and try to figure out how it will sound through a mastering chain. For processing, I won’t use a mixing desk, I’ll use a Manley Passive EQ, Clariphonic Parallel EQ, API 200, which is my go-to stereo compressor, and a Neve Master Buss Processor for mastering. I’ve also got a small summing desk, but it’s been reduced to a glorified plugin knob. Apart from that, I’ll just use a couple of distressors and an Avalon preamp.

The TesseracT album, Sonder, is available to buy through Kscope Music.

photo credits: Joseph Branston

MASSIVE was designed and developed entirely by Native Instruments GmbH. Solely the name Massive is a registered trademark of Massive Audio Inc, USA.