With world leaders becoming increasingly unstable and billionaires bent on building Mars colonies, composer Annie Gosfield’s operatic adaptation of legendary radio drama War of the Worlds couldn’t have come at a more appropriate time. Put together by The Industry, an artist-driven production company known for its experimental opera productions, the performance was artistic director Yuval Sharon’s vision for recreating the classic radio drama, simulcast across Downtown Los Angeles.

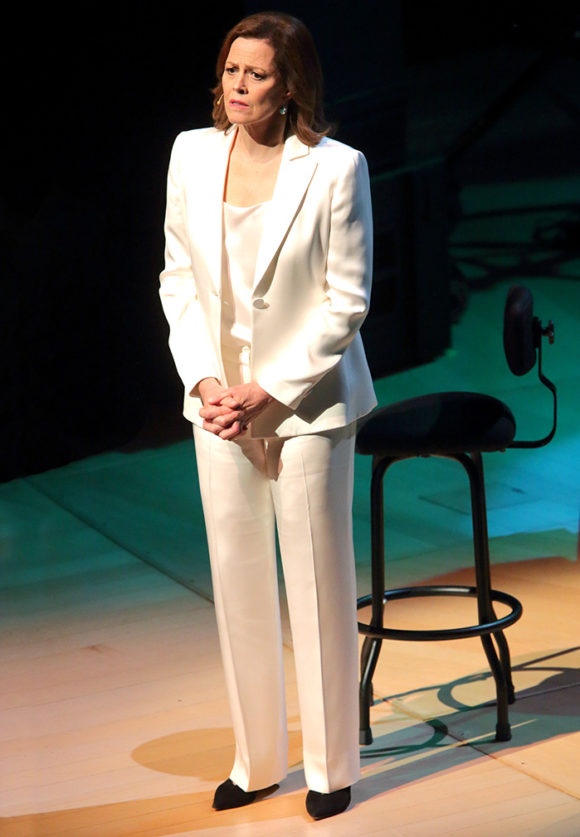

At the center of the performance, based on Orson Welles’ 1938 fake radio news broadcast about a Martian invasion of Earth, were refurbished WWII-era air raid sirens. Placed at three outdoor performance sites and parking lots in downtown Los Angeles, these sirens transmitted the otherworldly sounds of aliens — along with instrumental music and news reports back to the Walt Disney Concert Hall, broadcast to a live audience. The opera was performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group, and narrated by Sigourney Weaver at the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

This sounds like a pretty multi-faceted production, both from a creative perspective as well as for the audience.

Yeah. Each person got a different point of view of what was going on at Walt Disney Concert Hall. You would see the orchestra, you would see Sigourney Weaver, and you would hear the reports of the eyes and ears of the city. Basically, at each of the sites you would see a performer and there would be some staging, and you would hear everything except, say, this one person being interviewed by a meteorologist as an eye witness. So each of the experiences was quite different.

When were you hired onto the production?

I was brought into the project a little bit later than what might be normal for an opera. The project was started by somebody who just was very interested in these air raid sirens, and being able to use them for public art. He contacted Yuval Sharon, who was the director, and Yuval was just starting a residence at the Los Angeles Philharmonic. I was just about to have a premiere of a piece for two pianos and electronics, which were created with Kontakt. So they said, “How about Annie Gosfield?”

Given your background, it must have seemed like a great opportunity.

One of the reasons why they were interested in me for this project was because I’ve done a lot of work with radio sounds. It was a daunting project to say the least, there’s a small orchestra in Walt Disney Concert Hall, and we wanted to represent the Martian sound with a separate, isolated group.

So we had a subset trio of a soprano, who was singing wild, unearthly sounds I worked on with her, a keyboard player who played Kontakt, as well as celesta and theremin, and a whole battery of percussion instruments — some of which were enhanced by recordings I had made of the same percussionist that are played back on Kontakt.

The trio was in an isolated plexiglass box that was suspended high in Walt Disney Concert Hall, we called them “La Sirena ensemble”, and they were broadcast directly to the air raid sirens. They represented the composite sound of the Martians. It’s a performance about the Martians attacking Earth, so the Martians play a large role.

To complicate matters a little more, each of the three sirens sites had performers: one had a singer with three percussionists, one had a cellist and an actor, and one had a bass player and violinist and two singers. So I had to figure out a way to put it all together. Sometimes the individual performers would be performing with the musicians at Walt Disney Concert Hall, sometimes they would be performing with the La Sirena ensemble, and sometimes everyone would be performing at once. I had to find a way to have them perform effectively both by themselves, and together with other performers in other locations.

How did the fact that this was being transmitted in realtime across multiple locations affect the composition process?

It was a little tricky because we had a very high-end company doing the electronic communication, the sound relays, but it took them a very long time to actually confirm how long our latency would be. So I had to prepare a piece that could have a fair amount of latency. In the end they got it very tight, so there was a happy ending, but I had to write music that could be a beat or two off if necessary, or be this kind of floaty, ambient, atmospheric situation where things could be rhythmically forgiving.

And you know, when something is this complicated logistically, you have to mentally prepare for things going wrong, and create a situation where the show can go on if things aren’t perfect. Amazingly, things wound up being pretty perfect; logistically, it was like a magic trick. The latency was almost imperceptible. We actually had more of a problem with latency because we had some singers following the conductor inside Walt Disney Concert Hall, but hidden so they were using a video monitor, and they set them up with a digital monitor which has a certain amount of delay, no matter what — in concert halls we usually use all analog monitors. So the irony was that the latency problems we had were within the hall itself.

Where did the creative process start for you?

The initial idea and inspiration was radio, and dealing with a radio drama. I have a pretty large library of sounds I made myself of shortwave sounds — some broken shortwave radios, with a lot of tube noise and funky radios not tuned in, and radio interference. I’ve done a lot of research into jammed radio signals. I used these sounds a lot when we changed locations — like the radio dials being turned. The radio sounds had a changing role:,sometimes it was the foreground, and sometimes the background. The samples were played by two keyboardists; one was a member of La Sirena ensemble and in this plexiglass box and broadcast directly to the air raid sirens, and one was a member of the orchestra onstage at Walt Disney Concert Hall. So in some sections of the piece, there’d be dueling radios sounds.

The other important sound source for me was sampled recordings of the soprano, because I had to build the sound of an imaginary heat ray weapon that’s used to kill humans and destroy the Earth. I used a lot of layering of very high, unearthly, wordless vocalizations by the singer.

I used a lot of delay effects by slightly detuning a few instances of a sample, and then repeating it like a tremolo or a trill. The soprano would sing over a bed of layers of her own voice. So it was similar to a delay, but it was played live, and it could be reactive with the singer.

What was your technical team like?

We had two keyboardists playing Kontakt. We had somebody who was in the ensemble with the singer, and somebody who was onstage at Walt Disney Concert Hall. And we had a third electronics person who played some sound effects, because there were times when we had to be careful — if we overdubbed the heat ray sound too many times, it could stress the processor or create distortion because of the level got too high.

What was it like working with electronic instruments alongside orchestral musicians in this capacity?

When I initially met with the soprano, I played her a lot of sounds; air raid sirens and radio noises, just to see how she would respond, so the piece could really be built around voice and what the singer could do. It was an incredibly demanding vocal part, and we actually changed singers midway through the production. But we found our perfect Martian, a coloratura soprano named Hila Plittman. We could enhance these incredible things she could do vocally with sampled recordings of her voice, layering and detuning them to to create a really rich bed of Martian, so to speak.

Sometimes the vocal part was halfway between a voice and a theremin, and the sound wasn’t always recognizable as a voice. So being able to enhance it with layering and sampling and a little bit of detuning brought it into this very unearthly realm. Sampling the voice also allowed me to see how it would sound with different instrumentations. Being able to record and sample the singer in advance was a very important part of the compositional process.

What role did KONTAKT play in all of this?

Kontakt served two different functions. One was as a live instrument for the performance of the piece, which was very important; for that I used vocal sources as I just described, and a lot of radio sounds which were altered, detuned, layered — things that are really fun, and things that Kontakt lends itself to. The functions in Kontakt turn the audio sources into something really malleable, so in essence the radio sounds function as another instrument, using a keyboard MIDI controller. So a keyboard player who doesn’t necessarily know that much about electronics can follow a conductor, and bring in the sounds in on-cue, and bring them in in a musical way. I perform myself; I spend a lot more time composing for ensembles and orchestras these days, but this is a very important part of my musical development, working with samples and working with these unusual sounds in a musical and instrumental way. And the great thing about Kontakt is that I can build an instrument and have somebody perform it who doesn’t know about much about electronics, notated in a completely conventional way.

In preproduction, because I was collaborating with a director, it was really important to be able to give him MIDI mockups in advance. The other aspect of using Kontakt for me was as a plugin with a DAW: I would create MIDI representations in Cubase, and work in developing the piece with the director. It’s hard because, no matter what, the MIDI is never going to be as good as the actual people playing — well, I would say it will never really represent how it’s going to sound — but with Kontakt instruments, it actually sounded so much better than most MIDI mockups. A lot of composers don’t work in a DAW, and work in a notation program instead, and those MIDI reps can sound really bad. Working with Kontakt instruments made it sound much closer to what our final product was.

Would you say this was a pretty intimidating project?

I wouldn’t say intimidating but at times overwhelming, because we had to figure out how we were going to incorporate three outdoor “street theater” sites with a large group at Walt Disney Concert Hall, along with the subset of the “La Sirena” ensemble. What got me through it was that it was a very exciting project, and it broke down into individual pieces. I had to write quickly – I had a much shorter time than usual to actually deliver the finished score. Working with samples gave the piece a really individual character. The first sound heard in the opera is a sample that I made years ago of an old Serge modular analog synth. It starts with a wild, buzzing, repeating sound that’s echoed by the orchestra, which creates a funny juxtaposition of electronic sound and 1938-era era brass music. It was played by hand by the keyboard player — she’s a trained pianist and organist, but because of the nature of Kontakt and using it as an instrument with a MIDI controller, she could just read it and perform it very effectively.

Was tuning an issue?

It sounds wildly out of tune sometimes, but it just sounds kind of…wild. Pitch correction is something I’ve always had to deal with with samples so, you know, it’s not my favorite part of the job, but it’s part of the job. And sometimes you wind up with samples that can’t really be tuned conventionally. I’ve worked with a lot of factory and industrial sounds, and sometimes things just have very odd harmonics and it’s part of the sound — it’s part of their beauty.

One thing that’s been really important for me in working with Kontakt is that I can tweak the sample, so that it’s not difficult for the person playing it — I can hand them the finished product and they can perform it. In chamber music, I always try to write some kind of representation of what the sample is actually playing. That helps, but the people in the L.A. Phil were pretty remarkable — they didn’t have any problem with the electronics, and I think as long as you’re well-prepared and presenting something that is easy to play… it works out.

Were you happy with the final performances?

I was working with great singers and musicians who really brought the opera to life. All of the pieces within the overall structure came together really beautifully, and it touches on a lot of my own personal musical history, which made it a really fun project and a really great opportunity.

The beginning of the piece is ostensibly inspired by Gustav Holst’s The Planets, just because we needed a pretense to start the concert before the aliens attacked — just the way in the original War of the Worlds there was a series of performances from different ballrooms in New York City. So this was really a blast for me because I was taking my inspiration from dance music — largely from these old fashioned dance orchestras of the 1930s. So it’s drawn from popular music, with creative instrumentation and orchestration. It’s rhythmic, it’s for people dancing in ballrooms, and for people listening at home, so I could play with more vernacular pop culture references, and also incorporate electronics.

Sounds like quite a lot to incorporate into a single piece.

It was like having the big box of crayons with all the colors. It touched on everything from more abstract, improvised electronic music through more popular forms and songwriting, to traditionally-notated orchestral music. So there were a lot of references, but I think we all put together something that was extremely coherent and cohesive, and it goes from a kind of lighthearted but somewhat menacing beginning, and picks up pace with the radio sounds themselves, kind of like the radio play from 1938.

It seems that something this conceptually unique rarely comes to exist on such a large scale.

The actual project is hard to define. As I was writing it, people would say, “Oh what are you doing?” And I would tell them, and then at some point they would look like they didn’t believe me. And I asked the director Yuval, and he said, “Oh yeah, I’ve been getting blank stares like that for years!”

Title photo: Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times

“War of the Worlds” at Walt Disney Concert Hall photos by Craig T. Mathew, Los Angeles Philharmonic