Based on improvisational jams with a Buchla synth at Stockholm’s EMS studios, Irish producer Eomac teamed up with Japanese artist Kyoka to create the new, collaborative project, known as Lena Andersson.

Operating from Berlin and Tokyo, Kyoka works as a musician and composer, and is best-known for her chaotic approach to sound design, in addition to creating broken pop and experimental, yet danceable rhythms. Renowned for his critically acclaimed album Spectre, Dublin-based Eomac is a producer, DJ, label owner and one half of the distinctive techno duo Lakker.

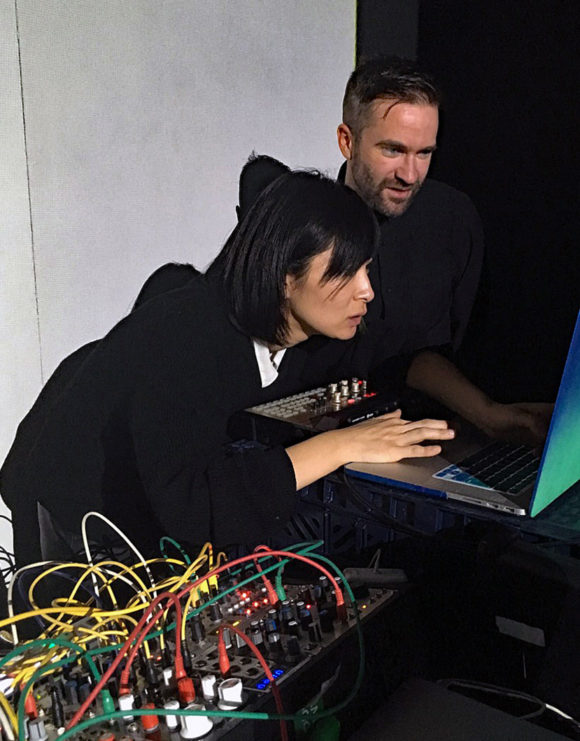

After Kyoka remixed Lakker’s ‘Three Songs’ in 2015, the two producers teamed up to create Lena Andersson, a project that was the basis for the debut album on raster, söder mälarstrand. Having teamed up after a collaborative Buchla jam at Stockholm’s EMS studios, the duo fused source material from Kyoka’s field recording collection with Eomac’s punishingly sophisticated sound design aesthetic. Both artists used Native Instruments tools during production, notably REAKTOR, FM8, and TRAKTOR.

When did you first begin experimenting with computers and software, and how did they help you to broaden your experiments in sound?

Eomac: It was around 2000/2001 I think. I‘d been in a band making electronic music before that but was mainly playing keyboards and not working within the computer realm. Around 2001, I got a laptop and a copy of Reason, which opened up a whole new world. The ability to build and shape everything myself — the whole DIY aspect — was huge for me.

Kyoka, you played piano before purchasing any electronic music hardware. Explain how this developed your interest in music making?

Kyoka: Playing piano could have been a big joy if the scorebook for my practice had allowed me to play the high notes on the keyboard, but I have to say I was proud of myself because only through seeing my improvisations did my parents give me piano lessons. Hearing sound was not so important to me at that stage, I was more interested in the system of recording and would ping-pong sounds by recording between two or three tape recorders. Before I got any hardware, I’d only use a metronome and my voice. After that, I found I could use a variety of sounds and would challenge myself by making drum patterns that a real human couldn’t play. Step recording was also a new way of recording that I got addicted to, and around 2003 the ability to see and edit sound waves saved a lot of time, I loved it.

You not only study how sounds are put together, but sound itself. How important is the use of field recordings to your working process?

Kyoka: Sound is just sound. I care about phase, clearness, atmosphere and action in a space, and field recordings provide me with unexpected panning, phase and atmosphere. To feel this in my daily life inspires me a lot. Daily life soundscapes, or music via field recordings can be like movie scene sculptures. I go to the forest or street early in the morning, listen to cars, bikes or train traffic, or go to where there are street performances going on. I record using either a Roland R-44 recorder or a microphone plugged into my mobile phone and some binaural tools.

Eomac: Kyoka has an amazing collection of field recordings that she’s been recording for years, from musicians playing instruments to ambient noise, conversations, her singing and lots of other interesting material. When working together, we use this to augment the synthesis material. It provides extra depth, texture and, sometimes, a more personal touch. Sound design has always been a huge aspect of electronic music for me. I love sounds and want to hear things I’ve never heard before, and try to achieve that in my own music.

How did you meet and what made you think a collaboration would be interesting?

Eomac: I was a fan, basically. Kyoka did a remix for Lakker and I thought it would be interesting to collaborate because there’s a fascinating mix of elegance and rawness to her music – a refined wildness. I really liked that and felt it was somewhat similar to my own music. About a year later, we talked about collaborating to see what would happen. It turned out well, we had a lot of fun making the tracks and Lena was born!

Kyoka: One midnight, my computer started to play a performance on YouTube. I don’t know why, maybe I clicked it just by chance, but I enjoyed the performance a lot and only later recognised Eomac was the same guy I’d had a coffee with a few days earlier. I feel my way of manipulating sound is a bit wild, but I also felt his sound is wild. I was happy to find a wild, manipulating sound friend and I enjoy the double-powered wildness of manipulating sound via Lena Andersson.

Why the fictional name Lena Andersson?

Eomac: There is a story behind it, but it’s Kyoka’s story, so I’ll let her explain.

Kyoka: It was my nickname in Stockholm.

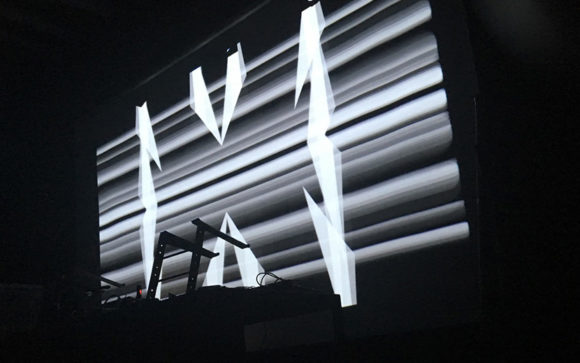

Explain the recording process on the new album söder mälarstrand. It’s based, I understand, on jamming with a Buchla synth at EMS?

Eomac: It started with the Buchla then we sampled it and brought the sounds into the digital arena to process and arranged them further. After that, we’d record the material back through an analog mixing desk ready for more processing.

Kyoka: We picked up on the most interesting and inspiring sounds from the Buchla recordings and kept adding more elements and constructing it. To keep the physical analogue texture, we tried various ways of recording, rendering and cable connections. For me, making the bumpy shape of sound in front of my face is always important.

The technology is old but the sound is brand new?

Eomac: Nice way to put it! We used a mixture of old and new technologies.

Kyoka: A lot of old technology was not made for mass production. I tend to trust the quality of that gear because it’s carefully created by passionate people who are pioneers in their field.

How was the album pieced together following those initial jams?

Kyoka: Eomac has a special talent for finding interesting materials for a new song and also unique and good grooves. That meant I could keep working with him without getting tired. It was really fun, and the album was completed without blinking. I soon realised we could work and make decisions much faster because we could be objective with each other about the music.

When did you discover Native Instruments technology?

Eomac: I first came across Reaktor around 2001 via an Irish electronic musician called Skkatter who released a track called Hate You on V/VM Test Records. The track is basically a cut-up of a Madonna track with lots of DSP effects. I was fascinated by how he made it and heard he’d used Reaktor. It totally confused me at the start, but the same year I got a copy of Kontakt and started using that heavily. I actually started using Reaktor a bit later.

How do you use it?

Eomac: When I use Reaktor, it’s usually as a synthesiser – especially for the more whacked-out, glitchy and textured sounds. I’m not a programmer and don’t build huge patches, but prefer to use the modules that are there and create my sounds from scratch. Reaktor features a lot in Lakker and we’ve been using Reaktor Blocks quite a bit recently. In the short time I’ve been using software, things have become ridiculously sophisticated. The trick is to find what works best for you, but what I think NI does really well is to cover such a wide range of working methods and provide sophisticated tools for each. From in-depth programming in Reaktor or finger drumming in Maschine to digital DJing, there’s a lot covered and the sound is very high quality.

Do you find NI’s software libraries give you the sounds you’re looking for?

Eomac: Sometimes, but what I like about the libraries is finding sounds I don’t know I’m looking for. I don’t normally use them if I’m looking for a particular sound because that’s not really the way I work. I usually build tracks from sounds I’m inspired by, either from recordings I’ve made, synthesis sessions or samples I’ve processed.

What do you use to supplement your use of the software?

Kyoka: I will use anything spontaneously, from tape recorders to wood, stone, water, hardware, fire, air, electricity, wind, musical instruments, turntables and mixers. All of these tools express sound equally, and Ableton is really nice software that widely covers everything from beginner to professional.

Eomac: It also made a lot of sense for us to use the same DAW so we could share and work on project files quickly and easily. Having common setups kept us in the flow of the tracks.

I read you’re a big fan of FM8 software for drum programming?

Eomac: I love FM synthesis and FM8 is quite simple to use and sounds great. It’s easy to shape sounds and I love its noise oscillator and filter for texture. I don’t usually look for complexity while making sounds; I prefer the sounds themselves to sound complex and interesting and keep the method of creation simple. FM8 has this for me because it has complex FM sound design but is also very useable. Usually I try to get the sound into the track as quickly as possible to keep some momentum and flow then I’ll tweak it from there.

I gather you’re both fans of TRAKTOR and used it a lot during your collaboration?

Eomac: We used TRAKTOR as a sound design tool. It was actually Kyoka’s idea and it worked really well when we loaded samples in and resampled them back out of TRAKTOR using FX and time stretching. It gave the sounds a totally different feel from the usual FX processing within Ableton or other units.

Kyoka: I discovered TRAKTOR when I bought the Hercules DJ controller. Since then I started to enjoy playing my demos on TRAKTOR. I like its audio engine and it helps me to be objective when judging a demo that’s still in progress. Actually, I was maybe the only person to project TRAKTOR onto a big screen for Ableton Loop 2017 while speaking at a studio session lecture.

Eomac, you’ve done some sessions for Native Instruments. Why did you want to get involved and do you plan to do more?

Eomac: I think it’s important to show how powerful the most basic tools of electronic music can be. Like the drum synthesis session I did using FM8, which showed some basic sound design tips for drums. I was making music for years before I knew how to synthesise a kick, and I remember how mind-blowing it was when finally I learned how easy it was. It was like drawing back a curtain and I found the more I knew about sound and how it’s constructed, the more I could demystify the process and the more interesting I could make my own sounds. I want to share with people how easy it is to do that, and I’m up for doing more.

The Lena Andersson album söder mälarstrand is out on June 28 via Raster-Artistic. For more information, please visit http://www.raster-media.net/detail/index/sArticle/1145.