In this new series, producer, DJ, label head, and mix engineer, Kevin McHugh – who you may already know as Ambivalent – sets out to explore some of the less obvious ways in which music producers can turn their existing skills towards a fulfilling career. Along the way, he’ll speak to successful figures from each field, diluting their wealth of combined experience into practical advice for aspiring music makers. First up, Kevin is diving into the glitzy world of film and TV composition.

For many musicians, there comes a moment where they contemplate completely centering their life around music. Inevitably, they’ll then face the question of how to do so while still taking care of life’s necessities. While the reality is that very few of us will ever live like Prince, David Bowie, or Aretha Franklin, there are many musicians who nevertheless do use their skills and instruments to express themselves and simultaneously make a living.

The team at the Native Instruments Blog have invited me to talk about the different ways that musicians and music producers are keeping music at the center of their lives while finding a means of survival that doesn’t necessarily put them directly in the spotlight. As someone who’s been fortunate to survive as a performer and creator, and who’s now using those skills to survive outside the touring life, I’ll share real talk and honest perspective. I’ll also speak to artists I know and admire, who’ve tapped their creativity in interesting ways. Some are colleagues in areas in which I work, and some are working in areas I barely know. We’ll share the unvarnished truth about how challenging some of these pursuits can be – life as a musician isn’t easy, after all, nor is it for everyone. But hopefully these features will contain wisdom and inspiration you can put towards your own efforts, and maybe you’ll have a chance to visualize ways that the tools and ideas you already use in the studio can eventually become the basis of a music-making career.

This first entry is all about composing music for the things we watch when we’re not in the studio. Chances are, if you’re a music maker, you probably pay particular attention to the music in movies and television. We’ve assembled a stellar cast of the people behind some of that music – they are each accomplished producers and musicians who’ve succeeded in branching out into successful careers composing for film, television, commercials, and theater.

We asked them a series of questions ranging from how they work to how they got into the industry, and what they’d recommend for anyone looking to follow in their footsteps. First, some introductions:

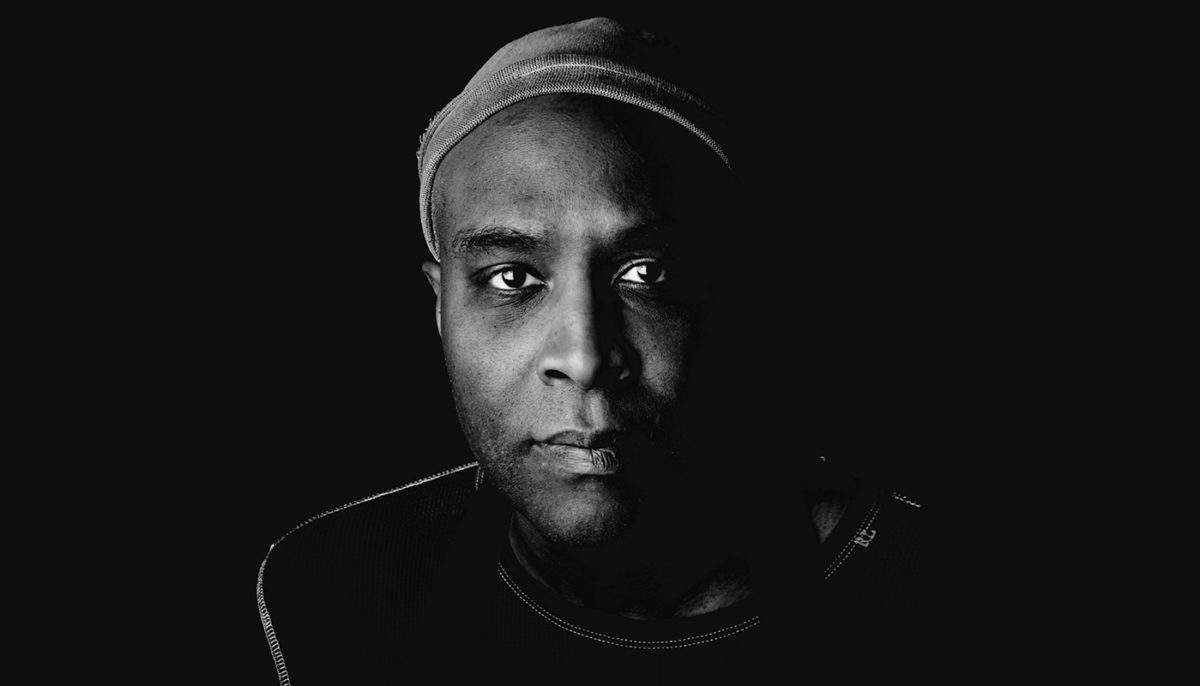

King Britt is a critically acclaimed producer, DJ, composer and educator. He has produced under his own name as well as aliases including Sylk130, Fhloston Paradigm, and Scuba. He co-founded Ovum Recordings with Josh Wink, toured with Digable Planets, and composed music for numerous movies and television productions. His compositions have been included in Miami Vice (2006) and True Blood (HBO) as well as numerous tv commercials.

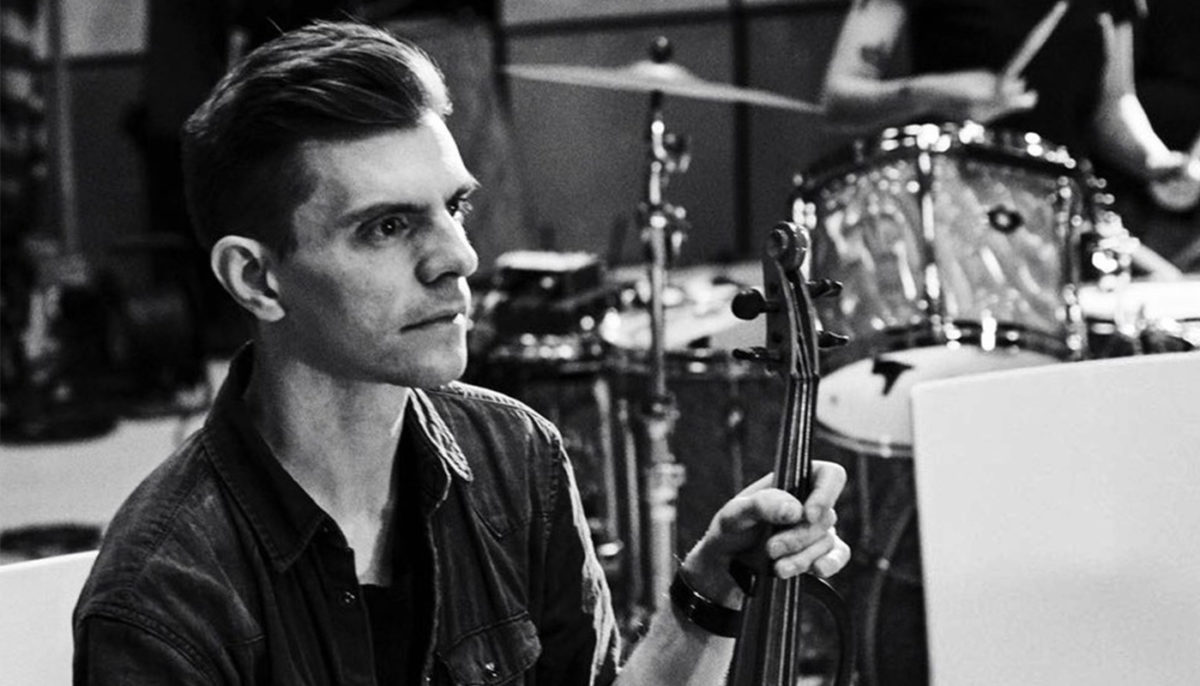

Chad Clark is a Washington D.C. based composer, engineer, and producer best known for his work in the bands Smart Went Crazy and Beauty Pill, whose album Beauty Pill Describes Things As They Are was named one of the “Best of the Decade” by TIME Magazine. His engineering work has included mastering and producing for the influential Washington DC music scene and the Dischord label. He has scored numerous live theater productions, performances and television including themes for PBS.

Craig Wedren is a musician and composer based in Los Angeles. His career began with the influential post-hardcore band Shudder to Think. He has since gone on to compose music for feature films including High Art, School of Rock, Velvet Goldmine, Wet Hot American Summer, and Laurel Canyon, as well as television shows Hung, GLOW, Shrill, New Amsterdam and more.

Kate Simko is a Chicago-born producer and DJ, now based in London. Her electronic productions have been released on influential labels including Ghostly, Get Physical and No. 19. She received a Masters degree in Composition for Screen from the Royal College of Music, and has composed for films including 20 Weeks, We Believe in Dinosaurs and the BBC Bitesize series.

Alexander Parsons is a British composer and musician based in London and a founding member of the Miro Shot collective. His composing work for television includes the landmark BBC 1 series Stephen: The Murder That Changed a Nation; the award-winning six-part BBC3 documentary series American High School and the BAFTA-nominated Channel 4 documentaries Muslim Drag Queens and Grayson Perry’s Dream House. Alexander has most recently composed scores to feature documentaries Rockfield: The Studio on the Farm and The Real Michael Jackson.

When you have a story to score, how do you approach the first steps of finding what you want it to be? Do you follow it in a linear path, writing scene-by-scene, or is there a thematic concept that you apply across the story?

King Britt: In my experience it’s a fine balance between what the director wants and keeping your sound signature. I was lucky when I worked with Michael Mann on underscoring Miami Vice. He initially licensed a song that I had done (w Tim Motzer) for the Sister Gertrude Morgan project. He liked the sound so much he asked us to create similar vibes through the movie. So half the battle was done.

Chad Clark: I tend to start with a concept of the sonic diegesis of the narrative. What I mean by “diegesis” is the sonic world of the narrative. When and where does the story take place? Does the music need to feel culturally appropriate to the setting of story? Once the diegesis has been established, yes, I begin to look at the script (or early footage if possible) and find the moments when music would feel needed or welcome. And I go from there. Scene by scene.

Craig Wedren: A few thoughts come to mind:

- is it a ‘genre’ thing? If so, there may be precedent and even expectations on the part of the creators and audience as to musical style.

- did anything pop into my head (like an insistent ear-worm) while reading the script or watching a rough cut? That might be a hint, a ‘way in’. This could be a sound, an instrument, a word, another piece of music, a color, almost anything..

- does it feel like like the ‘interior’ (i.e. relationships, characters, thought and emotion) needs support or clarification, or is it more the general World of the story that wants music? In other words, are we creating a musical frame/environment within which the characters interact, or are we filling out the characters themselves with the help of music.

- pinpoint a key scene or two (I personally feel a tugging at the gut – like a fishhook in my solar plexus – when one of these scenes rolls by), find a tempo that helps you really HEAR the dialogue in those scenes, then build from there, either with or without picture at that point.

- watch the cut or read the script, then free-write (music, not words), don’t think. See what comes up.

Kate Simko: The first part of my process is researching and creating a palette for the score. I start by getting into the story and characters as much as possible. I always make a lot of notes on the first cut and have a long spotting session with the director (and producer, depending) with a bunch of adjectives that I think describe the emotions scene-by-scene and also first intuition musical ideas.

Alexander Parsons: I often find the initial steps quite intimidating. Finding the sound of a film or individual scene can be tough. I try to start initial sketches really early into, or even before the edit if this is possible within the schedule. When a specific melody or instrument works, it is such a magical moment! From here, I’ll start writing directly to picture. As the cut is constantly being developed and shaped, it’s very rare that I’ll score in a linear way, as I tend to receive individual scenes (or reels) to work with, rather than a full cut of the film.

Can you talk a little bit about the process of collaborating with a director, and how you find the overlap between their vision for the story, and your ideas of how to treat the music? Do you share a mood board and concepts, or is it a process of hearing their ideas first and seeing a rough cut? Have you ever written a score to something that wasn’t finished enough for you to see?

King Britt: When doing a commercial – like I did Rolex for Michael and for Working Title – Michael gave me free reign to come up with a vibe to a written storyboard then he took that as temp music while shooting. Then I refined the song to fit the edits.

Chad Clark: I do often start with a “mood board” mindset with the director. (I’ve never used an actual mood board, but I like the general concept). I usually try to get a sense of the feel and rhythm of the script and then I hit the director with a couple of starter pieces. One or two short compositional sketches to see if the textures are appealing. If the director finds these sketches appealing, then we move forward.

Budget permitting, I always prefer to get involved with a project as early as possible. If it’s a play, I like to quietly go to rehearsals where actors are just beginning to run lines. If it’s a narrative film or documentary, I like seeing raw footage even before it’s been edited.

Craig Wedren: Some of my favorite experiences with directors that have led to the most fruitful, creative and memorable collaborations have been far more personal than technical or even strictly ‘productive’, at least at the beginning. Just hanging out, having a drink and playing music for each other is the best – like what we naturally do with our friends. That way, I know what they love (or hate) when I start my bit.

A lot of composers will write themes, sketches and suites, before seeing picture. I enjoy the freedom afforded there, but am also a very visual guy, so I get a LOT from picture – rhythm, style, color, the director’s intention.

Kate Simko: When I’m scoring a film I look at it as my job to compose music that helps the director achieve their vision. I really try not to be precious about what I want to do because directing a film is a massive project and the composer is coming into it at the tail end of the project. That said, if a director loves a piece of temp music that I don’t think fits exactly, I’ll peel the onion to figure out what elements they love, and write something new that hits those points and feels right for me too.

Alexander Parsons: I love this part of the process. The initial conversations are the most inspiring, as it’s often the first time you will really find out why the story is being told and what the intentions are. I prefer to talk in a non-musical way at this point, as it is a great way to get to the heart of the story, without thinking too much about whether the main character should be accompanied by a kazoo or a viola. Playlists can be a great musical starting point too, particularly when working with directors for the first time.

Are there instruments or sounds that you find yourself grabbing for every score? If so, are those sounds you use regularly use in your non-scoring compositions? Can you talk about some of the tools/instruments/sounds you use the most and why?

King Britt: I’ve always been approached for a certain sound that I have brought to the table but I’ve done quite a bit of remix live re scoring of films in clubs.

When doing Brother from Another Planet, I put a band together to truly bring Afrofuturism to the forefront of the sound. So keeping Herbie Hancock and my heroes in mind when choosing sounds as a homage to that vibe. So Moogs, Rhodes etc. When re-scoring Sun Ra’s Space is the Place, we approached it as more of an experimental mash up of samples from Ra and our layer of wildness while the film is being remixed in real time as well. I used Absynth a lot actually for this and Maschine.

Chad Clark: I like simplicity. I’m not a Richard Devine-type with an elaborate studio of exotic, modular eurorack instruments, etc. I start with pretty simple, econo tools. I use a pawnshop nylon-string acoustic guitar, a vintage Critter and Guitarri Pocket Piano and Bolsa Bass. And an Akai MPC. Those elements are often the starting tools in getting a sketch together. Nothing fancy. I have a love affair with Reaktor. I’ve been talking about it for years and years.

The interesting thing about me and Reaktor is I don’t quite understand it. I just jump into it and experiment, trial-and-error. My advice with Reaktor is don’t be intimidated by the complexity of it. Just jump into it like a kid jumping in a sandbox. I like to access the breathtaking array of imaginative Reaktor ensembles in the User Library and I just go… exploring. And I keep the record light on in my DAW, just in case I accidentally capture some cool sounds I didn’t expect.

My relationship to Reaktor is almost exactly like Mickey Mouse with the sorcerer’s hat in Fantasia. It’s easy for me to get into trouble, but it’s also a source of a lot of magic. You know? I think Reaktor is an element in almost every project I do, to a greater and lesser degrees. And it’s often as mysterious to me as it is to the listener. And I like it that way.

But software and sampling and electronica are only a portion of my process. I have a band — Beauty Pill is an excellent band of people who play conventional rock instruments (bass, guitar, drums) and I try to blend electronic/software processes with, you know, people in a room playing into microphones in real time.

Craig Wedren: I know I speak for many composers when I say we TRY to keep it fresh, experimental and discovery-rich when moving from score to score. I personally like everything I do to have a distinct (and hopefully unique) character. That said, there are plenty of well-worn sonic tropes (pizzicato strings for comedy and mischief, acoustic guitar for certain types of Indie films) and, again, expectations that directors, producers and audiences alike may have for certain types of stories. Given that most score is meant to be felt rather than explicitly HEARD, part of the fun is composing music that transcends genre and expectation without drawing too much attention to itself.

Kate Simko: I use pad sounds and ambient sounds a lot more in film composition than my own music. Especially under dialogue you often need slowly-morphing beds. I use Spectrasonics Omnisphere quite a bit. There’s a lot of layers so you can mute a few to get a more sparse cinematic sound. I also use Spitfire Albion, Cakewalk Rapture, and most recently used a lot of Arturia Pigments and Hive on a documentary about women in electronic music called “Underplayed.”

Alexander Parsons: I’m a violinist originally, so tend to start compositional ideas with this, alongside a range of sampled instruments, hosted mostly in Native Instruments’ Kontakt sampler. I have a library of instruments I’ve sampled myself (pianos, synths etc.) so will gravitate towards these, as well as some of the more unusual Spitfire Audio libraries that are available. Towards the end of the edit, I’ll usually bring in an ensemble of players, who will replace some of the samples and bring their own years of experience to the score. If it’s a more electronic score, I’ll turn to my hardware synths first – either my Prophet 6 or JP4 for more melodic parts, or the modular, if it’s something a little more abstract.

Scoring is a markedly competitive field to get into. What would you say are the biggest assets that help a musician find their way into work with film and tv?

Chad Clark: It was never my intention or ambition to get into scoring. Scoring kind of found me. My band released a song called “Ann The Word.” The accidentally cinematic sound led a few people in the arts to become interested in collaborating with me as a composer. Indie filmmakers, podcast producers, theater directors. I was kind of drafted into the DC theater scene and later into film/documentary.

I don’t know that I can give specific advice. But my general advice is to always try to do striking and memorable work, regardless of where you’re starting. Don’t be afraid of risks and don’t worry about your “brand.” People will notice the quality of your work and it will become your brand. “Ann The Word,” a song I initially regarded as a hopelessly weird/melancholic/obscure piece of music changed my life!

I was recently commissioned to write the theme for PBS’ 50th anniversary campaign. They found me because of Beauty Pill’s music. We’re not a famous band but we have cultivated respect. And respect pays.

King Britt: Well it’s funny I came into it through the director’s love of my work, but then there were a few jobs that I was like “this isn’t for me.” At the time I wasn’t really ready to be in the scoring world. I only want to be in it if the creative balance is there – not work for a director who wants to be a composer too. I will say a publishing company is vital in helping to get you scoring work and there are scoring managers but they have all said to me, we are all full. It is a very unbalanced world in terms of race as well.

Kate Simko: It’s all about delivering quality work and being easy to work with. There will always be a bump in the road during high pressure post production but just always remember you are there to use your passion and skills to achieve the director’s vision. If you keep thinking in that way then you deliver a score that lifts the film, and create lasting relationships and a good reputation.

Alexander Parsons: Firstly, knowing as much as you can about the area you aspire to work in is so useful – directors and editors you admire, as well as other crafts involved. There are so many ways to do this. BAFTA Guru is a great hub for career advice. Also ScreenSkills and WFTV (specifically for Women in the industry). Any knowledge you can take with you when networking is invaluable.

Secondly, the importance of having your own musical voice. Whether it be incorporating your own instrumental performances, or production techniques, having a unique sound is a great way to stand out. Where you compose unique material using Ableton and Push, a modular system or an acoustic guitar, use this to bring your own personality to your scores.