“Do you know what?” Darren White exclaims. “Trying to cook and answer questions is the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever done!” Even so, the drum and bass veteran better known as dBridge has handled the multitasking pretty well. Speaking from his Antwerp home, he’s prepared himself dinner whilst detailing his studio setup and musing on social media. But now he’s trying to bake while tackling a particularly tricky query about how things have changed over his 25-year career, and the dough has ended up on the kitchen floor.

Still, there’s something appropriate about White mixing his domestic and musical life in this way. His second album, A Love I Can’t Explain, is influenced by personal changes—marriage, kids, leaving the UK for Belgium—as much as musical ones. Stylistically, it covers the ranges from the drum and bass sound he’s long been at the forefront of, whether in the group Bad Company, as part of the Autonomic movement, or at the head of his label, Exit Records. Creepingly slow and colored with subtle soul, the album evokes quiet, homely spaces rather than the fury of a peaktime rave. Native Instruments caught up with White to hear about the album, and his longterm love affair with MASCHINE, with which he recently made a breakbeat-heavy Expansion, DECODED FORMS, alongside collaborator Kabuki.

I understand that a shift in your personal life influenced the album. Could you explain?

Yeah, these big things happened in my life. Leaving my home at the time, the UK. Getting married, having a kid. So I was using those experiences to guide my album. I’ve usually got a miserable side, but it’s a very happy stage in my life. So I was having to use positive influences rather than negative, shall we say [laughs]. But I managed to get some negative ones in there, [about] the state of the world we live in.

The spoken word bit in “Broadcast Pain” seems to have an anti social-media message: it tells this story about someone being in distress at a rave, and people filming rather than helping them.

It’s hard work, this whole social media thing. Having to be your own PR machine. I think a lot of people struggle with that, but maybe more people my age. I’ve come from a time where we paid people to do that. We used companies to get us into magazines and get people talking about us. Sometimes I get wound up by the lengths people go to get their name out there. There doesn’t seem to be a line that won’t be crossed any more. I think that’s been proven in the state of our politics now. The Overton Window has shifted, so what used to be really extreme isn’t any more. It feels like what people will do to get themselves noticed is getting more and more ridiculous. I have my standards of what part of myself I’m willing to give to the audience. But then it’s the struggle of: I may only be willing to give so much, but everyone else is willing to give so much more. And you can see that they’re getting a response from it. [On] “Broadcast Pain”, it was Damon [Kid Drama of Instra:Mental] telling the story. That’s the world we live in: rather than help someone, people would just broadcast it on Facebook Live. I’m not totally comfortable with it, but I suppose it’s no longer my world to be comfortable with, in some respects.

You’ve explored slower tempos, but often under other names, and not as extensively as on the album. What made you go down that path? And do you worry about it jeopardising your income as a drum and bass DJ?

I’ve always made music at different tempos. What I purposefully did with this album was [put it out] out under the name dBridge. This is something I wanted to do, and I felt that, if ever I was going to do it, now was the time. I wanted to write an album that reflects all the things that I’m into.

I’m going through a change at the minute that will potentially impact on my income. I’m lucky that I’ve got a family around me who are OK with exploring these avenues. There are risks, but I think my wife can see that I’m not truly happy. I’ve had this a few times in my career—I had it in Bad Company—where I’m earning great money but I’m not enjoying it. And I’ve felt that feeling creeping back again. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy playing DnB, but I want to bring in line ‘me’ the producer, with ‘me’ the DJ. I want to be able to play the music I make and play to an audience who will hopefully take it on board and be open-minded. Drum and bass [audiences], they want a certain thing, and that’s cool. And me, I want a certain thing. So am I going to carry on playing my stuff to an audience that doesn’t want to hear it? Or try and find the audience somewhere that does? Fingers crossed the bookings don’t totally dry out. I could quite easily roll out DnB bookings for however long and then become a nostalgia DJ or something. But that’s not something that inspires or excites me. I need a challenge and I’ve been putting off this challenge for too long.

From Bad Company through to Autonomic, it seems like the studio you’re working in has been a big influence on your output. Could you talk me through your studio setup at the moment?

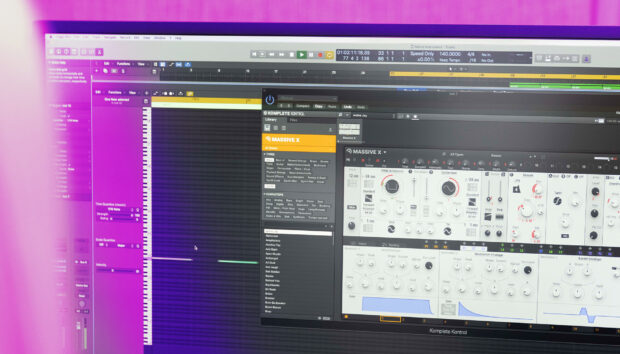

Well, Bad Company was hardware. Then we went through the whole in-the-box vibe: we embraced technology. We were letting go of our E-mu, letting go of outboard synths. Then in 2009, when I linked up with Instra:mental, the fact that they were still using hardware: it came full circle. It was a comfortable feeling. [Now] it’s about trying to find the best of both worlds. I like jacking things in, sticking things into guitar pedals. I like physically turning dials and switches. At the minute I’ve got the Mackie 32-8 desk. Elektron: Digitakt, Analog Four, Rytm—basically all of them. Guitar pedals, and a lot of synths: Prophet OB-6, Minimoog Model D, [Sequential Circuits] Pro One, the Dreadbox stuff. I use a mixture of Logic and Bitwig. Bitwig I’m transitioning to, I really like the flow of it. I find it’s a great addition in terms of working alongside the hardware. The album is me exploring all of my outboard gear, passing it through guitar pedals and recording it in. Because of the way the Elektron stuff works, a lot of it is almost live mixes: a lot of live tweaks. Which you can do in software, but it wouldn’t have the same subtleties or nuances.

Talk about how MASCHINE fits into your studio. You’ve been using one almost since its release, right?

For a long time it was my go-to machine for beat-making. It made me re-explore my sample collection, stuff I’d been collecting since 1999, early 2000. It made me look at [it] in a different way, which I really liked. The ease of dropping a sample in and manipulating it. I was able to look at a long sample from vinyl and skip through it quite easily, find these points and do these manipulations really quickly without having to think about it. That’s where MASCHINE excelled for me, this ease of manipulation and getting these ideas down really quickly.

You recently made an expansion pack for the MASCHINE, DECODED FORMS. Talk about how you ended up doing that, and the process of putting it together.

That was really cool. I’ve been doing New Forms with Jan [Kabuki]. We were doing a night at Watergate, and we were using Red Bull Studios. Native Instruments were really supportive of the project, got involved, lent us equipment, came down and streamed it. The offer came in, would we be up for creating an Expansion pack? For me, it was a new thing: creating sounds for other people to use wasn’t something I’d done before. The whole process of putting them together, using my hardware as a basis. And getting to use the macros—I hadn’t really used them before. So it was a great learning process, learning to use MASCHINE in an imaginative and creative way. I’ve used sounds from that expansion pack, ‘cos it’s pretty sick!