Award-winning composer and pianist Dustin O’Halloran is a master of minimalism who has honed his intimate sound with his groups, Dévics and A Winged Victory for the Sullen, along with his own albums, Piano Solos 1 & 2, Vorleben, and Lumiere. O’Halloran’s talents have attracted the attention of film directors across the world. To date, O’Halloran has scored for films such as Sofia Coppola’s “Marie Antoinette”, received an Oscar nomination for his collaboration with Hauschka for “Lion” as well as having soundtracked Nike’s powerful Colin Kaepernick ad. From his Berlin studio he spoke about his musical beginnings, blurring the lines between the analog and digital worlds, and the challenges he faces when composing for film.

You have had a very diverse musical career. Which musicians or composers have inspired you throughout your life?

My very first musical interaction was with classical music. When I was first learning the piano it was Chopin, Debussy, Mozart, Bach, Beethoven – you know, the classics. They have always stayed with me in some way. I’m pretty much a self-taught pianist. I picked things up much later in my life and started studying on my own, that’s when I started to get serious with the piano. The piano was my first interaction with music and it was always my first love. As you get into composition, the whole orchestra is represented by the piano. It’s such a great instrument for writing music.

When I started to discover bands in my early teens, I was listening to a lot of music coming out of the UK – a lot of 4AD’s music, Joy Division, and The Cure. One of my biggest influences growing up were Cocteau Twins. Ironically, many years later when I had my band Devics, with Sara Lov, we ended up signing with their label, Bella Union. That was like a full circle of musical inspiration. I’ll never forget, Simon Raymonde from the Cocteau Twins played bass with us on a couple shows in Italy and we played some of their tracks. As your musical journey continues, you’re always keeping bits and fragments of the things that have influenced you.

How does your creative and recording process work?

I’ve always built my own studios and collected a lot of analog gear and microphones. I love taking analog sounds that I’ve recorded and shaping them in the digital domain. A lot of my process is a hybrid of both these worlds.

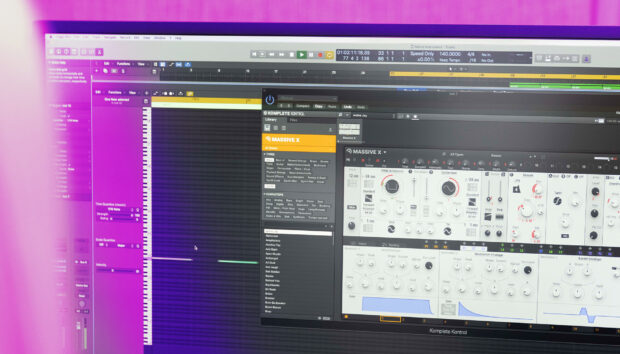

When Hauschka and I were working on Lion, he was sending me files and I was working on a lot of the melodic structures. At the time, Hauschka was working in Logic and I was working in Pro Tools. Hauschka actually started learning Pro Tools for me, which worked out really well because he was recording so many piano parts. I’m now also working a lot in Ableton, and that’s such a different creative process.

I’m more and more creating my own library of sounds and my own KONTAKT instruments. The ability to create your own libraries is a really great way to have your own sonic identity. If the digital process gets really complicated, I lose it a little bit. I like to work and create ideas quickly. I find Kontakt so immediate and the sound is great.

What kinds of instruments are you creating?

On the last film I did, I worked with Francesco Donadello, who’s been a collaborator of mine for a long time. What I was able to do with KONTAKT is create entire libraries and entirely new instruments all from the material we generated. Modular synth is a bit of a journey because you can never really go back, you can never really save anything, you have to capture things as they go. That’s how I like combining these worlds, taking the time to really get great analog sounds and then take advantage of the digital side: Building instruments, creating things, making changes. With film, you’re always having to adjust things.

One of the instruments that we built a few years ago with KONTAKT was a bowed piano library. We used different materials to bow the strings and different velocities too, so that as you play it, the sound changes depending on how you play the instrument. That was really effective and came out really nice.

How do you use KOMPLETE KONTROL S88 during your writing process?

For me, KOMPLETE KONTROL S88 is unique, in the sense that I am probably different than most piano players; I’m not looking for big dynamics, I’m actually working in the lower dynamics. I’m always trying to play the piano as soft as I can and record it as intimately as I can. There’s something really beautiful about having the mics turned up really loud, getting every single detail. You’re able to play very evenly and with a really soft touch. This way you can get a really unique, rounded recording. I find that this controller gives me that dynamic in the lower register really beautifully, and I’m able to reproduce it much better. I’m able to emulate a lot of the touch that I’m able to get with a real piano. It’s probably the first time I’ve been able to get it so well.

Can you tell us about An Ending, A Beginning?

An Ending, A Beginning was a piece of music that took a little while to finish. When I came to Berlin, Peter Broderick was one of the first people that I met, and he added the strings to this piece. He has such a beautiful way of playing violin, a really delicate touch. It was a piece of music that didn’t have a home, it didn’t have a record. I wasn’t working on a record at the time, and I ended up putting it on a compilation. It was a record that Fat Cat made, which was my label at the time. It was from a tour that I did with Hauschka and Jóhann Jóhannsson. Then it began a second life after being used as the opening track on the Late Night Tales compilation curated by Bonobo. This piece of music has always stayed with me.

For the performance, I played the piece with the new KOMPLETE KONTROL S88. I don’t think I could have recreated it without this new touch that this keyboard has. I find the S88 much more precise, in the detail and especially with the action. It gives me the most return, but also the most definition in the lower registers, which hasn’t really existed before.

You have lived and worked in many different locations over the years. Do the places you live influence your compositions?

I can’t imagine that any of my records would have come out the way that they had if I hadn’t lived in these places. When I lived in Italy, I was very isolated in a small village and all I had was a piano. Moving to Berlin was a huge shift for me because I went from being isolated to being connected to a lot of great musicians. When I first moved here, I met Nils Frahm, Jóhann Jóhannsson, Adam Wiltzie, Hildur Guðnadóttir – a lot of amazing people that I got a chance to collaborate with. Berlin has been a really big part of my musical journey.

I grew up in Los Angeles: it’s home, but it’s a strange city to call home. A lot of people find LA very intimidating and you can get lost in this endless landscape of city – but strangely for me, it makes sense. When I’m going between LA and Berlin, there’s a little bit of recalibrating your rhythm. Berlin has a really unique rhythm as a city, and it’s very different than Los Angeles. Berlin is just such a cultural mix and there’s so many great creative people here. I just did the People Festival and that was a week of collaborating with 150 different artists. That kind of experience never happens in Los Angeles; where you get this insane, crazy, collaborative experience.

Did you always want to compose music for film?

When you grow up in LA, the film industry is always there. To be working in it doesn’t feel so strange because you’re always around it in some way. I grew up in the birthplace of film itself, Culver City. Culver Studios was one of the first film studios ever in existence and they did all the early silent films. I lived very close to that. I think that when you’re raised in a place where there’s that kind of history, it feels kind of natural.

The next movie that’s coming out in October is called The Hate U Give. It’s all modular and orchestral, plus a little bit of percussion. KONTAKT was a big part of that. I don’t think I could have created a lot of these sounds and pieces without it.

This was my first time recording at Fox Studios. We recorded in the 21st Century Fox Studio with a 40-piece string orchestra. That room has such an iconic sound. You hear it and it just sounds like a film score. The orchestra was amazing, I was really lucky to have great players and a really great conductor. There was a lot of extended techniques that we captured because I wanted a lot of the sound of the bow. I love to hear some of the imperfections. We used the classic Decca Tree to capture the main sound of the orchestra, but then we used a lot of ribbon mics to get the close-mic sound of the orchestra. That was great because if they’re playing very soft or if they’re doing textural stuff, when you hear the sound of the bow, which you might not capture so well with the Decca Tree, it just adds a lot of character and tension. The film gets pretty tense so I needed to hear that more intimate, human element.

Do you arrange all of the strings yourself or do you have an arranger do that?

I’ll arrange everything myself and then I’ll have an arranger come in just to help me balance some things and make sure that it’s notated in the right way. In The Hate U Give in particular, I created a lot of drones with modular, and then we emulated the drones and doubled it with the orchestra. It was very detailed because we were creating harmonics that are coming in and out. I had Mark Graham, who’s been an orchestrator for John Williams for a long time, help with this project. He was amazing.

Collaboration is a huge part of what you do. Do you find it hard to separate yourself from your art when you’re working with others?

Film work is always a very big collaboration. You’re collaborating with a script, you’re collaborating with actors, you’re collaborating with the director. It’s the biggest collaboration you’ll ever do. There’s always some compromise in that kind of collaboration. If you’re lucky, you work with a director, producers, and people who really want all of your ideas – who are willing to be open to how you view the music.

There’s always compromise as you get into the process and navigating this is always tricky – trying to maintain your own sensibility while trying to understand what the film needs. You can think about what you want, but sometimes the film speaks louder than that and you have to find a way to make that work. I think that’s the challenge of being a film composer. When I’m working on my own material, it’s a blank canvas and you’re not fighting with anything. The challenge there is you’re starting from zero so you really have to pull everything from yourself. There is no script. There’s no storyline. You have to create your own imagery.