After getting his start as a tape op for CBS Studios, Steve Levine’s career has seen him working with The Clash, The Beach Boys, The Honey, and producing Culture Club’s seminal albums. Not only that, he’s a Director of PRS for Music, has been on the executive board of The Music Producer’s Guild, and he’s often heard and co-presenting BBC Radio 2’s The Record Producers with Richard Allinson.

In terms of production advice, then, Steve Levine is a font of wisdom – and his collection contains some truly classic drum machines. “Here in the studio I’ve got my original [Roland] CR-78, my original Simmons [SDS-V] and my original Linn [LM-1],” Steve says as he casts around the room to scan his collection of vintage kit. “Dave Simmons himself put an interface on the back of my Linn so that I could use it to trigger the Simmons. That CR-78 and that Linn have been on many of my famous songs.”

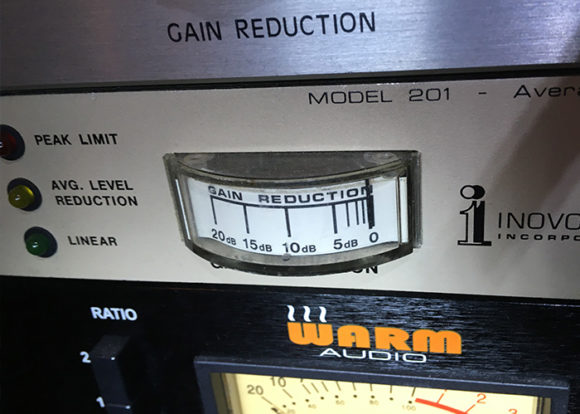

Those classics and others take centre-stage in Steve’s new sound pack. Alternative 80s sees him meticulously sampling hits and loops from his impressive collection through his Neve 1073 preamp, via his unique spring reverb unit, and then onto tape.

But Alternative 80s isn’t solely for the purists, is it?

Exactly. For a modern twist, I’ve also used brand new things like the [Analogue Solutions] Mr Hyde, a Watkins Copicat… that’s why it’s alternative! If you want raw, clean, 80s sounds, those are available, but if you want some more experimental loops put through messed up filters for unusual tones, you have that as well.

There are lots of single shots too – on the Linn you can tune each drum, so I’ve done lots of different tunings. In the case of my CR-78, I’ve got MIDI on it so I was able to do separate kick, snare and so on.

It’s quite a line-up already, but what other sought-after bits of gear are included?

I’ve also got a Roland Rhythm 330, the precursor to the CR-78, which is quite a rare one. Technically speaking, it’s a 70s drum machine, as is the Korg MiniPops [7], which hasn’t even got ‘Korg’ on the back – it has ‘Keio’. It works really, really well messing around with the speed control. There’s a few classic late 70s and early 80s songs that have those. I won’t say what they are, but it’ll be obvious when you hear them.

I’ve taken out some of the drum sounds from my Ensoniq [ESQ-M], which are quite interesting as well. I also discovered in my archive my original alternative sounds for the Linn Drum. Believe it or not, those are on cassette, but they sounded so crusty that they sounded really good. I transferred that at high fidelity including tape hiss, and then I denoised them for the purists that don’t want the noise.

What is it about these classic boxes that’s carried them through the ages? Are they objectively great pieces of kit, or have they just featured in influential music?

I think it’s both those things. In the case of the Linn, the younger generation will recognize those sounds because they’ve been on so many classic songs, from Prince to Don Henley. That rimshot is the sound of “Boys of Summer”… and if you want the handclaps from “When Doves Cry”, that’s the one. Culture Club, “Karma Chameleon” … those songs are snapshots of that period. And those songs are absolutely ingrained in you – whether you’re 60 or 16, you probably know those songs.

Secondly, I was always trying to push the envelope on fidelity. We now know that the sounds on the Linn are not full quality; they’re as good as they were for the time. I would always want to replace the sounds, add things or tweak them in a certain way… and yet over the years, I’ve got to learn – as we’ve increased fidelity – that they have a unique place in a track.

And is the method behind getting up there and actually using a hardware drum machine responsible for unique outcomes as well?

What’s very interesting with the Linn particularly is that it forces you to program in a certain way, and therefore arrange the song in a certain way. I would really encourage those who have Maschine to program in that way – don’t just copy and drag in the computer. You wouldn’t just drag and drop on a Linn, you would copy but listen.

You get much more focused on the arrangements – you delineate it in a way that you don’t do when you just drag and drop. You don’t delineate subtleties between bar four and bar five in the intense way that you’re forced to do with an actual drum machine.

It’s all about the personality and the subtleties of the inaccuracies, then…

In the case of the Linn, and the CR-78 particularly, we all know now that their timing accuracy wasn’t mathematically perfect, but it lent a certain shape to those songs. When we put the Linn down live, I would program the drums and I might run the CR-78 in time with it and use the Clock Out at the back of the CR-78 to trigger, let’s say, the Jupiter-8’s arpeggiator, and have the musicians play chords through it.

Duran Duran uses that kind of effect – the machine is timing it, but the human is doing the chords. When everything else is overdubbed live, you end up with these ‘interactive fields’, which I think is great. You don’t get that if everyone just quantizes everything to everything.

You’ve been using these machines since they were made, and you’ve been combining them with every technology that’s come along since then. Which facets of modern music technology do you appreciate the most?

I think the modern restoration and repair tools are fantastic. I’ve used iZotope RX a lot to clean up the ones with the tape hiss on, although I’ve left everything that went through the Watkins [Copicat] with the hiss on.

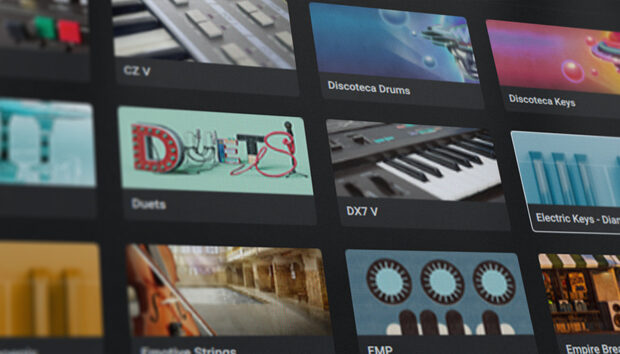

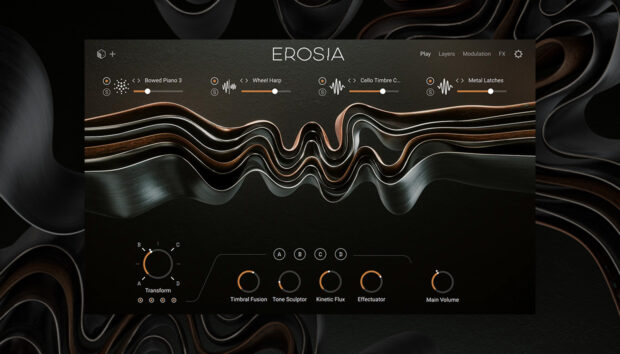

I like the emulations of all the Roland plugins, the Korg plugins, but then I also love Native Instruments’ creative plugins – especially those that use random modules and things like that, they’re very musical and very creative. I love Kontakt – it’s my main sampler. I like the compressors and the de-essers… there’s not really many plugins I don’t like; it’s just a question of how you use them!

You’ve used a lot of your homemade secret boxes to create the pack too. Do these stem from your electronic engineering background?

Yes, and I’m still fascinated by it to this day – even if I’m just soldering a cable! There’s an immense amount of satisfaction when you build your own stuff and it works, or even if it doesn’t work on the first go…

Back in my Culture Club days – on “Do You Really Want To Hurt Me”, the guitar sound [in the post chorus] – that “wah-wah-wah-waaah” came from a kit that I’d bought. It was supposed to be a noise gate. I don’t know what I did wrong, but instead of gating it, it sort of chopped off the front off the signal.

…and when Roy [Hay, Guitarist] was doing that part, I just said, “I’ve got an idea Roy…” That could be the earliest of my homemade items.

That’s probably something that we miss today – although it’s possible for things like that to happen in the digital world. Do you have any general wisdom for today’s producers, based on what you see and hear these days?

Record properly, get a decent mic – one that’s appropriate for the job. Don’t be afraid to re-amp something. Even if you’re just in a flat and you’ve got a tiny, tiny room, you’ll be amazed at the difference that makes. For the Roland 330 samples, I’ve recorded them in stereo. It’s got a speaker in it, so one side is the miked speaker and the other side is the DI.

Check the phase of your sounds. A lot of people have 15 kick drums all cancelling each other out. Decide what the hell you want, then of course choose appropriate sounds and don’t be frightened to EQ out what you don’t want.

A lot of people don’t listen loud enough, and they’re pushing the levels on input so that everything’s clipping like nonsense… or conversely listening so loud that their ears are so tired, and they’re EQing everything. Listen on headphones for some time – you can hear the positioning.

Consider not just additive EQ – EQs work both ways: plus and minus, and you can do some very, very good tone sculpting by taking away what you don’t want, not just boosting everything. Those can be instant ways of using the samples, just be creative with them!