Deconstructing art and profiting from your efforts now go in hand. Why sell the cake when you can sell the cake mix too? Native Instruments provides the ultimate guide to putting together your own sounds and sample pack, ready for retail.

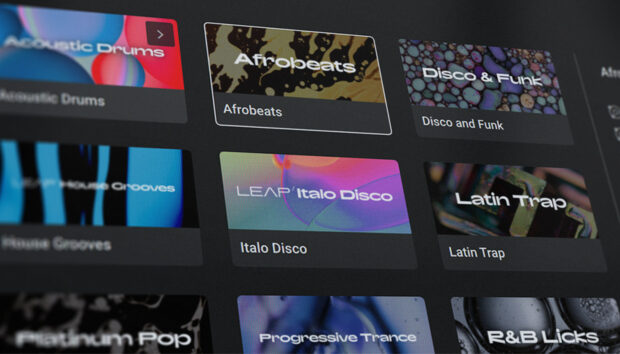

While the sample market has traditionally been driven by a select handful of sound design studios, newer platforms like Sounds.com afford increasing opportunity for highly talented producers, musicians, engineers, artists, sound designers, and labels to create inspiring sound inventory.

Spanning beats and basslines, to vocal hooks and weird modular bleeps, the most memorable sample collections are far more than simply a “musical skeleton” for building tracks upon. Many have proven intriguing masterworks in their own right, their sonic DNA giving rise to entire genres.

Successful sample-pack production is a combination of effective workflow, process and curation, and while each sound designer has their own approach, there are some universally enduring conventions.

Interested in joining the ranks of the sample-making glitterati? Read on to find out how.

Guidelines, conventions and standards

Before you begin the process of sample-pack creation, it’s crucial to be familiar with production standards and conventions.

When a producer begins to make a sample pack, they will first be supplied with guidelines that specify exactly what the company expects to receive. These guidelines remain fairly consistent between resellers.

Here are some fundamentals you will need to know:

1. All sounds used in creation of loops and hits for sale should be 100% royalty-free. Selling a retooled James Brown breakbeat, for example, is legally dubious. If in doubt, leave it out.

2. Loops and one-shots (e.g., percussion hits, synth stabs, FX sounds) are usually supplied in 44.1kHz 24-bit WAV or AIFF format. Even if creating a deliberately lo-fi sound, the finished samples must be in these formats, so that end users have access to broadcast-standard loops.

3. Loop duration is generally two bars. On occasion, four-bar loops are acceptable, but only if warranted (e.g., a chordal progression that lasts four bars). Anything beyond four bars would rarely be acceptable for rhythmic loops. However, certain non-tempo-dependent elements (noises, textures, environmental recordings, etc) can be of any length.

4. ALL elements should be normalised to 0dB! For audio engineers, this part of the process may well be deemed a cardinal sin, as the combined output level of multiple normalised loops could exceed 0dB, creating digital overload. However, all samples in a collection should peak at 0dB, or as close as possible. This helps maintain reasonably consistent volume throughout the pack; it also allows easy integration of elements into DJ sets or mixes in which mastered (i.e., peaking at 0dB) tracks are incorporated.

5. All loop points must be checked to ensure they use zero crossings. If they don’t, undesirable digital clicks can occur, rendering the samples of limited use. Test all loops by looping them in your audio editor – if you hear clicking at the loop points, add short fades (5-10ms) or crossfades (adjust by ear) to correct this.

6. File-naming conventions must be adhered to, though they can differ between providers. Sample filenames typically include title, tempo and key information, to help producers easily slot them into their tracks. Let’s take a look at a few examples of how this works.

The Analogue Ghettotech Tools Vol.1 pack on Sounds.com contains a loop labeled “Trxgt Bass126 90s Organ Cmin”. This can be decoded thus:

- Trxgt – An abbreviation of the sample pack’s name and the company who made it: TRX Machinemusic’s “Analogue Ghettotech”

- Bass – The sound type/category.

- 126 – The tempo of the loop in beats per minute.

- 90s Organ – A given title for the sound. In this case, the title is highly descriptive, telling the user exactly what to expect, although titles can be abstract too.

- Cmin – The musical key of the sound – this one is in C minor.

“Trxgt Hat126 Raw Tekjakk” from the same collection follows the same naming convention, but without key information as it’s a non-tuned instrument loop.

7. How many loops and hits do you need to make a well-rounded sample pack? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer, with quantities varying by publisher, pack genre, and purpose. Just keep in mind that quality over quantity should be of uttermost importance.

Tighter packs are popular impulse downloads – for example, “Extraordinary Kick Drums Vol 1”. At the other end of the scale, you have the more extensive, comprehensive genre-focussed collections, such as “Noisefactory Construction Time Vol. 1 – Commercial Deep House Reloaded”. These frequently contain unusual or value-added content like plugin presets, MIDI files and even preloaded performance templates for your DAW.

Reading the descriptive text of existing packs can help you get a feel for typical pack sizes and price points.

Best practice file-management tips

Publishers generally request that content is delivered in a specific, organised file structure. Before getting creative, it’s helpful to create empty template folders reflecting this structure, to be filled with the requisite number of samples as you create them.

Spreadsheets can also be an effective method of keeping track of pack content, both during the production process and for ‘stocktaking’ once you are finished.

At the most basic level, keeping written records of completed elements will help you to identify where you are in the process, and what content still needs to be created.

Strategies, themes and instrumentation

You want your sample pack to sell, and just like marketing an album, an attractive backstory can help generate interest in your offering.

So before commencing the creative process, it helps to devise a clear narrative scope and collect reference material for personal inspiration.

1. Choose a working title or theme. This could be genre-based, with a particular creative twist (e.g., Ghostly Garage Vocals, Dusty Atlanta Trap Experiments, Stoned Electro House); a technical descriptor (eg. Mutant FM Basslines); or a combination of these. Although it may eventually be changed, a confident working title will strongly influence the direction and aesthetic of a sample pack. Key here is both inspiring your own creative process and making your pack stand out in a marketplace awash with uninspired titles!

What labels, artists, sounds, and instruments might be useful as references? Form a collection of your own research material, to inspire and anchor your work. When creating a techno pack, for instance, your references could reflect anything from Rodhad, through to Juan Atkins, or DJ Pierre.

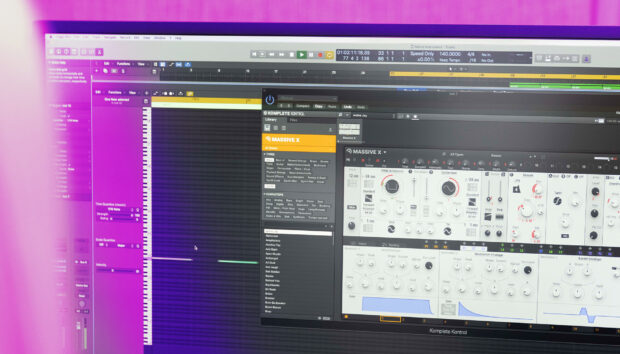

2. When it comes to instrumentation and signal processing, a consistent workflow and DAW template will help keep your sessions moving forward. And if you work solely in the digital domain, it can be beneficial to emulate a physical, hardware-oriented workflow.

For example, a sample pack focusing on ’80s synth-pop might begin with collecting reference tracks from three or four key artists, researching common studio instrumentation of the era, and finally emulating these in a physical or digital environment.

For “Analogue Ghettotech Tools Vol.1”, the DAW working template was inspired by the analogue synths, drum boxes and sample sources that defined the ghettotech genre. All recordings in the collection were processed using the same chain of analogue-style overdrives, filters, limiters and compressors, adding a distinctive and consistent tonal sheen and EQ profile. For this pack, a deliberately restricted range of virtual instruments was also used (e.g., Native Instruments’ FM8, and a basic TR-909 drum machine emulation in Reaktor), mimicking the limited studio tools used in typical ghettotech productions. Finally, additional noise, grit, hum and distortion artifacts were added, emulating older analogue equipment.

3. One useful technique for generating cohesive ideas is to compose loops in context, rather than as isolated elements. By generating two-bar musical themes containing parts kick, bass, percussion, synth, and so on, it’s easier to develop compelling loops that work in real production situations.

However, instead of exporting the parts to the same folder in the pack, as with a construction kit, each part is instead placed in its relevant folder (kick, bass, etc), alongside other similar parts. Once five or ten such themes are written using the same template, a new session can be started, with slight variation in instrumentation.

To give an example of how you might approach this method, the first loop session might comprise ’80s analogue drum machine loops, vintage monophonic synth bass, found-sound hat variations, and treated ‘vinyl’ percussion. A second loop session could utilise a variation on this basic template (e.g., alternate drum machines and synths from the same era) while maintaining general tonal continuity, workflow and signal path.

The result is a sample pack that feels cohesive but doesn’t push the user to simply recreate your source themes.

5. Export, edit, repeat. The vast majority of work on a sample pack tends to be spent on post-production, editing and curation.

To generate 100 great loops, it’s useful to shortlist 150 or more potential candidates before selecting the best elements for the cut. Unused content can always be repurposed for future packs.

Where loops like basslines or chord progressions are programmed using MIDI, make sure to export these as MIDI files with name and key, all as you go. MIDI files provide great extra collateral for producers looking to modify loops.

6. Once a batch of raw loops has been generated, a final mastering pass is helpful to compress and finalize finished ideas. Audio editors like Audacity are great for batch processing files to ensure they’re formatted, faded and processed consistently.

Audio demos, descriptive text and artwork

Audio demos are often the ONLY way for potential customers to hear how a sample release works as a cohesive whole. So once your pack is finished, it’s vital to provide great audio demos to promote it.

Because demos are indicators of the scope and sonic potential of a sample pack, they should be created without any additional effects processing – although basic volume limiting on the master bus is acceptable.

Look to create between two and ten short demos, each showcasing key elements of your pack, e.g., beats, chords, bass, etc. That doesn’t mean your bass demo should contain only bass sounds, but that it should highlight bass elements in the context of other sounds from the pack.

Artwork, branding and descriptive text are the icing on the audiological cake and should be created in high-resolution formats where applicable. Again, only use what you have the rights to use.

For commercial packs, descriptive tags (embedded in the WAV file, or supplied separately) have two big advantages. First, they help users find your pack in the first place, when they are searching online for packs in a specific style, or even by a specific author. Second, good tags allow producers who have purchased your pack to easily find the right sounds within it. As an example, some typical tags used in Analogue Ghettotech Tools Vol.1 are ‘analogue’, ‘jacking’, ‘acid’, and ‘ghettotech’.

Increasingly, niche sample collections also make reference to the artists and labels that inspired them in their descriptive text.

In conclusion

Frequently overlooked by producers, the art of sample-pack authoring is a creative – and often long-term income opportunity.

For those who shun the limelight, producing royalty-free loops is a satisfying way to engage in the wider musical conversation, free from the burden of public identity. Sample packs, can also work to the contrary, allowing a producer or brand to reach a new audience by finding new and exciting ways to engage with music makers.

As a technical skill set, finessing the art of consistent theming, rendering, processing and cataloging loops (in addition to demos, artwork and written collateral) can take some time to perfect, yet with practice can prove deeply rewarding, creatively and personal surprising for producer and user alike.

Check out Sounds.com for further inspiration, loops, and more.

If you’re interested in creating sound packs for Sounds.com, please email partner.inquiry@sounds.com.