Last month, Kyiv producer Koloah released “Serenity,” an album written in the build up to, and in the wake of, the February 24th Russian invasion. After several weeks of being unable to listen to music – let alone make it – he sat down with NI to explain how he finished the album and started producing again.

On March 1st, the war in Ukraine came to Dmitriy Avksentiev’s door. As gunshots sounded and tanks fired on the streets 500m from his Kyiv home, Avksentiev, one of Kyiv’s most prolific electronic artists, made the decision to leave.

“I took my friend who lives nearby, took her cat, found a car, and we left Kyiv, ” he says, “it was the hardest trip… we didn’t sleep.” With his laptop, two t-shirts, a jacket, and his cat Misha, he traveled for 70 hours before finding a room with a family in the western city of Stryi. “I think I didn’t speak for two days because I was empty… dead inside.”

As Russia’s military slowly amassed on Ukraine’s borders ahead of the invasion, Avksentiev, known under aliases Koloah, Voin Oruwu, and Tropical Echobird, continued to make music.

“I started before [February 24th] when I already had this feeling, because they were gathering forces for more than two months. Each day became more scary. A lot of people didn’t believe the war [would happen] but I was sure.

“I started to produce this album. When the war started, for 20 days I couldn’t do anything at all.”

After commercial projects came to a standstill he was left looking for work, a client got in touch with a music project for mental health healing. It was the first time he had produced anything since the invasion began. “My task was to make music to help people fall asleep,” he explains. “Just imagine, I’m making music for people to fall asleep and there’s a huge war outside.” The jon became the impetus to get back to music making. .

“It was super good for me because in this mediation of airy, sleepy music I was calming down and thought, ‘Damn, I need to make this into my album.’ It was the punch to finish the album and release it.

“For me it was like therapy that helped me get through those first three difficult weeks, which were the hardest in my life I guess.”

With a director’s background from previous work in TV and film, cinematism, progression, and storytelling are integral to Avksentiev’s music. Where many artists struggle to produce longer bodies of work, the album format provides enough ground for exploring expansive worlds of sound.

“Everything begins from text. I start by writing a kind of statement – I have this director’s background, I was making scripts, and I really love to write.

“I make a mood board; pictures, videos, some symbol boards for each album. I try to make some mythology and astrology just for myself or for the artwork to make it easier for designers.

“Then I produce music in this mood. You can go and come back to it. When you have a strong core, in my practice with texts and mood boards, the final product is more powerful.”

The technique has produced an impressive body of work, where each release hints at some greater world or narrative of which the music plays just a part, though the music he makes now is immediately shaped by the war. “I can tell you that now, I can’t make music with drums at all. I heard these rockets and bombs and now it’s really hard to make something hard and heavy like I did before. With [alias] Voin Oruwu there are a lot of rhythms there, this dark energy. Now I can’t really do it because it’s still hard.”

As well as a therapeutic tool, Serenity is an education in atmospheric sound design – imbued with expansive pads and hybrid textures that effortlessly blend long reverb trails, voices and rhythmic sweeps. With much of it written far away from his studio, Avksentiev searched for new ways to find the sound he was looking for.

Second track “Seachless” is one such example, made in one day on a trip to Cyprus just days before the invasion to escape the overwhelming pressure of the military buildup on Ukraine’s borders.

“That track, I made on February 18th. I took a [Teenage Engineering] OP-1 and my laptop and that was all. It was almost all VSTs; I used the Arturia CS-80 and some stuff from Spitfire Audio, and Maschine software I used as a VST in Ableton to make some pads from the standard plugins.

“I have my two favourites – the Bass Synth (it sounds so subby, I love it!) and a pad which I use in almost every track (but with different reverbs so it sounds different!).

The track “was supposed to be called ‘Speechless’ but I made a mistake and saw the word ‘Seachless’ and thought, ‘well I’m surrounded by the sea so it works.’ I went to the sea and shot this video you can see on my Instagram of some waves. I made it all in one day, shot it, and released it.”

The track is proof that, even far from his picturesque Kyiv studio, where cat Misha has a permanent perch among the synths and keys, Avksentiev can build his Vangelis-esque soundscapes with remarkable dexterity.

The same was true after he decided to leave the Ukrainian capital. “When I was living with the family [in the western city of Stryi] I made everything with VSTs – it was a challenge because I normally use a lot of hardware.

“When I used to make dubstep I used Massive, and I didn’t open it for years. But there in the west I opened it and it was super cool to go back to the roots.”

Stryi is also where final track Dyvo was written – a striking closure that includes a powerful choral layer washed with phasing, ethereal pads. “At 4pm the city was already empty. I was walking like a ghost, trying to listen to music but I couldn’t. I walked past a cathedral and heard something was happening.

“I went in and it was this beautiful song – about the [Annunciation to the] Virgin Mary. I know this prayer, it’s very famous, but I had never heard this recreation of it. I was like ‘Wow! This will be the last song of my album.’ I recorded it on my iPhone, came home, and from this song I rebuilt the album.

“The album is very dark and beautiful, but this last song is for brighter times that say to you that everything will be okay.”

In the last two years, Kyiv has rocked. I wanted to live in Barcelona or Berlin, but now I want to live in Kyiv.

With such a tight focus on visuals, artwork, and storytelling, there is still more to be done. Avksentiev is working on an audio-visual rendition of the album so people “understand what we feel here.” Like all men aged 18-60, Ukraine’s martial law means he cannot currently leave the country, but sharing this experience is something he wants to do.

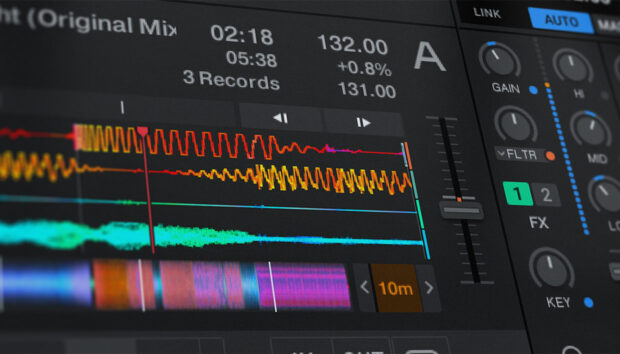

Anybody who has seen him perform in the past will be aware of his commitment to live shows. Usually based around a collection of synths, a mixer, and Maschine Mk3, they blend a broad palette of sounds and influences that coalesce into whatever sound is right for the venue in question – be it a rave or even a castle.

“I use an Ableton project with Maschine on a separate channel on the mixer where I have all the percussion, drums, and bass. I have some analog bass, but the sub bass is only from Maschine.

“In the first two groups I have percussion that I always play live. At the beginning it was basic, but then I bought [Spotlight Collection: West] Africa for some variation.

“In the other groups it’s just the Maschine drums – I try not to use [external] plugins because of my computer. I have a few sends in Ableton, but the project is really big.”

There’s always scope for experimentation – especially under the Koloah moniker, which has developed from a bass-music-oriented sound to one that is closest to the “real” Dmitriy Avksentiev. “I made Voin Oruwu because I wanted to go in another direction, but it transformed into a techno project… I had a cool life, played Cxema, all these big festivals.

“But for myself I can’t do a lot of techno, especially right now. That’s why Koloah is more emotional, more varied. Koloah is an art and cultural project making statements.”

Since finishing the album, he has returned to Kyiv. In recent years, the city has grown into one of Europe’s hotspots in fashion, film, and music – exporting young, creative talent across the world, and importing new tourists, partygoers, and explorers. Although many people have left (Avksentiev quipps that although Kyiv has been known as “the new Berlin,” there are so many Ukrainians there now that it has become “the new Kyiv”), he intends to stay.

“I’m telling you. In the last two years, Kyiv has rocked. I wanted to live in Barcelona or Berlin, but now I want to live in Kyiv. It’s a super place, super energy, super nice places, super clubs, super nice people… the music scene… everyone is so nice!”

Serenity is out now via BandCamp, with all profits donated to the Refugee Support Fund.