Movement Tracks is a collaborative project aiming to revolutionize music therapy and help patients with cerebral palsy and Parkinson’s disease walk again. Incorporating the latest technology, this leading team of composers and therapists in Austin is enabling people to move once more, using the power of music. Native Instruments paid a visit to find out more.

Music-based therapy has been around for decades but, for many, it is not the most accessible form of treatment. Patients typically require expensive one-on-one sessions and even one visit a week costs more than many can afford. Even leaving price aside, the supply of music therapists cannot match demand, with just 6,200 licensed practitioners in the United States. This seems like a big number, until you consider that over one million of the population are afflicted by Parkinson’s alone, and each patient requires personalized rhythms, tempos, and even timbres, to effectively re-learn the simplest of movements.

The Movement Tracks project, produced by The Center for Music Therapy and Hope Young, aims to solve this problem of access through a creative approach to composition, and using a broad spectrum of virtual instruments in KONTAKT combined with innovative technological delivery systems.

Get physical

Arriving at the center we find Emily Morris, Movement Tracks’ lead music therapist, guiding a patient through a short warm-up. The patient spreads her arms wide, holding onto tension bands attached to the ceiling. Morris plays a simple three-chord progression on an acoustic guitar, the smooth long strums giving a loose rhythm for the patient to follow as she pulls down on the bands. The timbre of the instrument matters, and Morris carefully watches the patient’s movements, adjusting the tempo and power of her strumming to match.

If they’re on the ground and can’t get back up, they hear these songs, and can get back up

The same principles apply to walking on a treadmill. “If a patient with Parkinson’s struggles with heel strike, then you need a more significant downbeat, like a bass tone. If they struggle with hip flexion, then you use something like a cabasa sound on a beat that has movement. This helps control their movement, relax their hips, without them knowing,” explains Morris.

Movement tracks

The compositional side of Movement Tracks is helmed by Cassie Shankman, an Austin-based musician who had an interest in medicine from a young age, but ended up studying film music at the University of Texas, before working with another Texas resident, iconic director, Terrence Mallick. Together Morris and Shankman compiled a list of the most common afflictions, then matched them to certain rhythms and instruments. Using a proprietary system that allows control of each stem track and the overall tempo, physical therapists can personalize the recorded music for each patient.

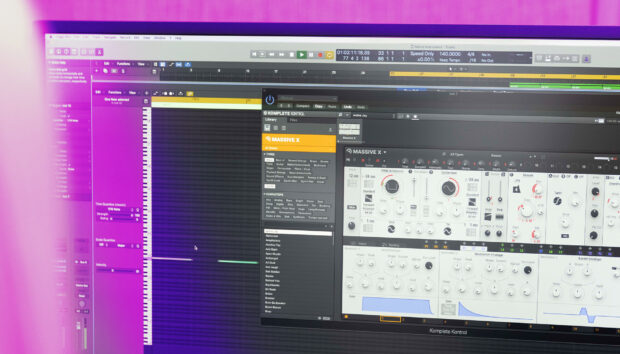

Developing a database of tracks tailored specifically to patients struggling with movements such as hip flexions and heel strikes – both essential for normal walking – proved a unique compositional challenge for Shankman. It involving much experimentation and testing, which she accomplished through the use of modern software. “Kontakt is huge in the research and testing process. It’s hard for me to play all the instruments, and I can’t pay for people to come in and play, but I can use Kontakt as a composer canvas to test ideas and record them,” says Shankman.

These instruments address another difficulty with recreating the music therapy experience virtually: studies indicate live music is much more effective than simple recordings. Fortunately, it is not just the presence of a therapist strumming a guitar that keeps people engaged, but the actual fidelity of the music. Low quality recordings are less effectual, making it harder to test out new ideas. This is how professional virtual instruments can step in, allowing testing with various compositions in high fidelity. “We do testing with Native Instruments sounds,” says Shankman. “They sound live – we can see the response and test out changes before we record the live version.”

Walking music

To achieve the fidelity they needed and with the first round of composition complete, Movement Tracks brought a jazz combo into Austin’s Bismeaux Studios to perform the music. Founded in 1990 by Ray Benson of Asleep at the Wheel, it is one of the city’s premiere recording studios, responsible for albums by country greats like Lyle Lovett and Willie Nelson. Capturing high-fidelity music is nothing out of the ordinary at Bismeaux, but the composition process is a far cry from a country singer penning lyrics and chords in a notebook. Movement Tracks has the tall order of writing 30-minute songs that can be slowed down to as low as four beats per minute without driving a patient crazy.

The program focuses on cerebral palsy and Parkinson’s because they are both neurological motor disorders, but the contrast between the two diseases offers Movement Tracks a wide variety of test subjects. In both cases the brain does not communicate properly with the body, but musical cues can help. The trouble is that each individual case can include everything from tremors to catatonic states to spasms. The wide spectrum means there is no one size tune that fits all, but technology like the Biodex Medical Systems Gait Trainer 3 helps them get close. A small computer mounted on the front of a treadmill lets users select a song and caters the speed and other variables to specific patients.

While there are many more in the works, Movement Tracks has already released two songs, one targeted at each condition. Since Parkinson’s patients typically skew towards the more elderly, Shankman composed a tune in a big-band style called ‘Street Walking’. For the more realistic sounds she relied on virtual instruments like Una Corda, and Session Strings.

For cerebral palsy patients, the song ‘Animals Everywhere’ is more playful and uses instruments that produce cartoony and exotic sounds. Some of the primary VSTs were from the Discovery Series, including India and West Africa.

Although Morris and Shankman focus on medical applications for their music, the project recently caught the ears of Smart City engineers at SXSW 2017. The popularity of wearable tech creates new opportunities to tailor music to people’s everyday experiences, both for people afflicted with movement disorders and those without.

Despite these exciting possibilities, Shankman is clear: “We don’t want to replace music therapists. But people can only afford a few sessions a week, and this is something they can use at home. If they’re on the ground and can’t get back up, they hear these songs, they can get back up.”

“We want to find a way to give physical and occupational therapists the tools that we use, but not just make a mass market CD and call it music therapy,” Morris concludes.

photos: Dan Gentile