Cheche Alara is a musical powerhouse. The Argentinian has performed with Christina Aguilera, Stevie Wonder, and Alicia Keys, produced for Natalia Lafourcade, directed the Grammys, Latin Grammys, and American Idol tours, and composed for just about every major broadcasting company in America. In short, he’s done it all.

Coinciding with this week’s Latin Grammys, we sat down with Cheche at his home studio in Los Angeles. Read on for his advice to Latin musicians looking to follow in his footsteps, as well as reflections on his musical roots and the changing role of technology in his work.

How did this whole journey start? You’ve gone from making music in your homeland of Argentina to Hollywood.

I was born and raised in Buenos Aires, and I started working when I was really young – around 13 or so. I was playing with bands that were focused on New Orleans jazz – 1920s, 1930s at the most – and it was a great scene to learn technique from. Then I started doing a lot of musical theater, which was a great experience to learn chops. And right around when I was about to finish high school, I got a scholarship to go to Berklee, and I wanted to give it a shot. I was planning on going back home around six months after. That was 1992, and I’ve been here ever since.

So you had no plan? You just followed each lead?

I know it might sound weird, but it just happened. It wasn’t part of a plan. You can only plan so far in this world when it comes to music. One thing led to another. I lived in Boston while I went to Berklee, then I did my Masters at USC on a scholarship, too. I thought I was gonna be here six months or a year.

Were there other musicians in Argentina that were an inspiration for you? Other players or producers where you said, “I wanna be like that person”?

Growing up in Argentina, I mostly looked up to American, British, and Canadian musicians. Because I grew up listening to jazz, my ultimate idol growing up was definitely Oscar Peterson, a Canadian; but people like Lalo Schifrin and later on people like Gustavo Santaolalla put a huge stamp on film and albums that are amazing.

But once I moved to the US – and I think this is very common for people that come as immigrants from other countries – you rediscover your roots. So I became way more appreciative of who I was by being here, but acknowledging more of what it means, how good it is. When I was in Argentina, I was playing musical theater, I was playing jazz, I was playing rock; when I moved to the US, I started playing salsa. But if you talk to people that are first or second–generation immigrants, it’s always a rediscovery of your roots after you put down roots in the US. It would be so wrong to deny who I am – I lived almost 20 years in Argentina – and I stay in touch with it and go back often and have family, and a huge part of my life is still there.

When you got to Los Angeles, were you looked upon as a Latin musician, or as a musician who just happened to be from Latin America?

When I came to LA, I had to find work. I had to make a living. And by default, by being from South America and speaking Spanish, I worked heavily in the salsa and Latin jazz circuits. Back then, there were a lot of outlets to play live music in LA. I was working a lot. It got to the point where I had a beat-up 88-key controller in my passenger seat, and I just left it there because I was playing every night.

How did you move into the mainstream?

I was playing a gig at The Baked Potato, and I was approached by someone who was putting together a band for a new artist named Christina Aguilera that no one had heard of. And I thought she was a Latin artist, and I heard her voice and was like, “Holy cow! This girl can sing!” and within a month I was touring with her during the “Genie in a Bottle” days (I’m dating myself drastically!) and she went from being completely unknown to everyone in the world knowing her name.

What was the transition point from being a player to being a producer?

Early on I realized that I want to put my stamp on things that I work on as much as possible. And as a keyboard player, I could only leave my stamp up to a certain point. So I thought, “How can I get more involved in creating these live shows?” I wanted to be a musical director, because at that point I had more creative control. I started directing the tours for American Idol – really big tours – and I really liked it, and that led to quite a few years of doing mostly musical direction work, which I loved. Then after a few years, the same thing happened: I realized, “Hey, this is great; but I’m playing music that’s been recorded. I’m recreating albums for a live show. I want to be involved in that other part, I wanna be a part of the albums.” And I started doing a lot of sessions as a player, learning a lot, watching a lot – how different producers worked, how different engineers worked, and learning what to do, and quite honestly, what not to do. But around 2010, I made a clear decision: I wanted to start producing proper albums. I wanted to be in charge. Not from a position of having to be in control, but of wanting to create. To make more of an artistic statement that had to do with me as a creator. And for about 10 years now, I’ve been producing albums – and I love it.

How has technology played a role in your workflow?

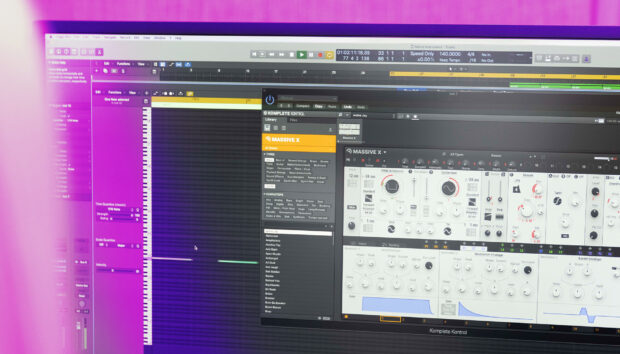

It’s definitely become essential. When I went to Berklee in the mid 90s, for example, you could still say “Well, I’m a musician and I don’t really deal with technology. The engineer will do that.” Now, it’s impossible to make it as a musician without knowing technology to a certain degree. I personally love it. I love technology. Technology is an instrument. It’s a vehicle to make sonic art. It’s a whole new, ever-changing field where there’s constantly new tools that let you do things that you couldn’t possibly do in any other way. And for people who are classically trained, once you get that it’s not a way to ‘cheat,’ it’s a whole different palette at your disposal. More colors that you can use to create. And I find it fascinating, because it makes me question what I know constantly whenever something new comes out. And it makes me go back to being more innocent. Like, “Oh, if I do this, that happens,” whereas when you hit a C on a piano, you’re gonna hear that C. And it’s endless, because it keeps evolving. I love technology. It enables me to stay in shape, to stay alert to what’s going on, and particularly for scoring film and TV, it’s essential. I just couldn’t do it without technology.

What kind of advice can you give young music makers in other Latin countries who are trying to break into the US market?

It goes hand in hand with access to technology. As a generalization, in Latin America, it’s hard for people to be able to afford a lot of gear. The fact that NI makes great stuff that is affordable is awesome. It’s better to have Komplete and a keyboard controller than collecting all of this vintage gear. I think gear is important – but in my opinion, completely irrelevant. The real question isn’t how much gear do you have; it’s what do you do with it, and do you know how to use it? Because if you know how to use one piece of gear, you’ll get way more mileage out of that than if you have ten pieces of gear. As a young musician in Argentina, I didn’t have any access to technology. But particularly for people in Latin America, we’re used to overcoming tough circumstances and challenges, and if people can apply that to their music, I think they’re gonna get ahead and be able to break into any market eventually. We’re used to things not working out, so we have to find ways around it to make it work for you, and I think that’s a wonderful skill. So when it comes to technology, focus on what you have, on what you have access to. Learn your craft, learn your instruments, learn your gear.