Nik Nowak’s creations may look like something out of a Mad Max movie, but the Soundpanzer, along with his newest work The Mantis, are in fact mobile soundsystems – both capable of delivering huge volumes of bass, anywhere, any time.

Read our interview with the sound and installation artist below, and find out how TRAKTOR provides the bass ammunition behind his latest vehicle The Mantis.

You work as a freelance artist, musician, and DJ. Is that correct?

Actually, I’m a visual artist by nature. I studied Liberal Arts under Lothar Baumgarten, and have a background in painting, Fine Arts, and visual art. I had a hard time accepting the term ‘musician.’ I worked a lot with recordings, sampling and sound collages, until the format began to sound more like music, and even like film soundtracks. I mainly see myself as an artist, as you can see in my studio, where there are lots of paintings, drawings, and sculptures standing around. Installation, sound, and music have always been key elements for me. The form of my artistic works, which I have been shaping for 15 years, has developed into this kind of sound sculpture, which is also a form in itself.

The engineering can’t be so easily separated from the musical side of things. Partly, I build soundsystems for a specific piece based – for example – on special recording techniques, like the Infra/Ultra project. When producing, I’m normally thinking about the way the speaker will operate. If someone wants to create a mixdown for a different medium afterwards, like vinyl, then it’s an entirely different step, because the way I produce would need to be re-thought for it to work in.

This was always secondary for me, except for the collaboration project Schockglatze, which had a focus on club music and with which I released the Warlord EP in 2015. With my other projects, the soundsystem itself is always visible as an integral part of the sound sculpture. I really don’t need anything else. Soundsystem culture as such is not an industry in the traditional sense, it can also function autonomously.

So you create your sonic work only for the moment, and not for it to be heard later?

Images and sculptures, for instance are static, but with music it’s completely different. Music always exists in relation to time. This is where it intersects with physics, maybe more so than I realize. During my studies, I always looked at sound explicitly as a sculptural material, in which I mean it’s a space-structuring material that is so extremely tied to the time domain, such that it’s an amorphous material that can never stand still. The soundsystems however became the sculptural format that stay even when there is no more sound.

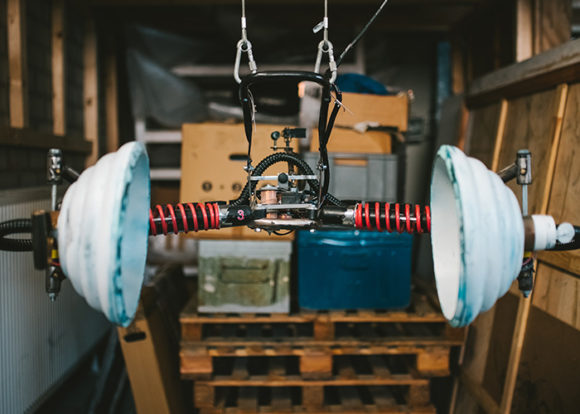

Even when a soundsystem is off it still holds an incredible potential that makes it strong as a sculpture. The membrane of a loudspeaker is a fascinating object because I feel like there’s so much within this black hole, even when it’s just lying in the room after being removed – and the bigger the membrane the bigger the effect! That’s why there’s a 21” subwoofer in The Mantis, because it’s simply mindblowing to know how much air you can move with a speaker that size. Additionally, one can see the black paper cones as a projection screen for uncountable musical codes. This potential fascinates me.

What does sound mean to you?

Sound has always taken up all my attention. Even in school, I was very bad at focusing on anything visual due to auditory distraction, and that continued into adulthood. There used to be these car tuning meetings right outside my studio door, and the bass always vibrated into my studio. I noticed how much I became occupied while working on graphics, and how it influenced my mental state. I started to learn more about the phenomenon of psychoacoustics, and tried to make compositions with samplers. Equipped with an MPC1000, a Waldorf Pulse and Fruity Loops, I created soundscapes for myself, in order to dive into a state in which I could concentrate and focus on my graphic projects. I noticed that was always building similar soundscapes. The bass frequencies were always very pronounced. At some point I started building loudspeakers, as good subwoofers were very expensive as a student, and I wanted speakers which should be able to really render what I’d written. I don’t think they were acoustically accurate, but I effectively built them like an instrument and made music with them. It wasn’t done in a pop-cultural sense but as an all-around work of art, made of sound and sound, sculpture.

What is it that fascinates you about bass and soundsystem culture?

I came into contact with the Frankfurt techno scene pretty early on. On the other hand, hip hop, reggae, and dancehall also played an essential role for me, as there were a lot of American barracks in the area. One key experience was attending a dub reggae club-night when I was 13, which was an epiphany for me. It wasn’t a proper Jamaica-style soundsystem, but they did their best to build something similar and honestly. It had therapeutic value for me. The music was set up in a way that I could completely lose myself in the bass and the drums. The physical energy of the speaker-stacks made me feel like I was swimming in the music, like I was underwater. It really shaped me, I’d never heard anything like that before.

In 2015, almost 20 years later, and my Panzer project was apart of the Jamaica Jamaica! Exhibition at the Philharmonic Hall in Paris where I curated a dancehall mix in collaboration with [American DJ] Bassmechanic.

In that context, I realized how much this culture and music is embedded in my work. As I dealt with perception and psychoacoustics, the low-frequency spectrum became increasingly relevant because of its impact on our psyche and bodies. In the course of my studies, I did tons of research and testing, and at some point landed at the topic of acoustic warfare. I started to better understand how low frequencies impact the midbrain and amygdala.

Basically, infra-sound triggers a warning system which causes stress and fear. From an evolutionary perspective, it’s responsible for physical reactions such as rigidity and escape.

It became increasingly interesting to me because I’d question why, since my youth, I go to clubs and expose myself to the most extreme bass I could find. And I’m not the only one, there’s an entire generation doing the same thing. Maybe our world is so loud and stressful that we need to come up with some sort of counter stress method to get back in tune with ourselves, or can only reach a level of inner peace through counter-noise. These kind of thoughts are not necessarily essential to the experience, but they often lead me to a new idea for work.

To what degree do soundsystems have historical meaning and political components?

Soundsystems are basically a means to take over public spaces guerrilla-style, in order to create room for confrontation and discourse. Within the scope of my work, I curated an exhibition at MARTa Herford museum in 2014, which focused on the worldwide phenomenon of mobile soundsystems. As far as civil soundsystems are concerned, things work in a similar way, but with different local characteristics. It is, at its core, a confrontation with one’s own identity, more specifically as an emancipatory project that makes them an essential element of independence movements.

On one side it creates an immaterial place within the music, but also claims real space through sound. That is fascinating. As if one had a temporary, parallel reality that one can unfold like a tent and then turn back off and take it to the next spot without leaving behind any impression. There’s a book named The Temporary Autonomous Zone – not only can a soundsystem provide an autonomous zone (such as the club), but it can also temporarily alter rules and power dynamics. It’s no wonder that modern soundsystem culture developed mainly in Jamaica and impacted the whole world, because Jamaica is a place where a multi-ethnic society had to free itself and heal from the trauma of violent abduction from the African homeland and the enslavement by Europe, and had to reinvent itself as a society beyond the Eurocentric character of institutions.

How did you come up with the idea for the first Soundpanzer, and The Mantis?

As children, my generation experienced a kind of simultaneity of war and peace, which left a strong impression. The presence of the American military in my hometown Mainz, where there were many barracks since the end of WWII and throughout the Cold War, has most likely shaped my work today. Today, I consider it a privilege to have grown up in Germany and Europe in the 80s, when a lot of things developed into positivity when the ice of the Cold War started to melt. The Berlin Wall fell, borders were removed, Europe established itself, which used to be separated through east and west started to grow together over the following decades. We witnessed a time in which many emancipatory movements happened and a diverse, tolerant society developed. Today, we see many of those achievements threatened. We are again experiencing an era of building walls and fences, of people being separated. The Mantis is strongly inspired by the loudspeaker trucks used by the Studio am Stacheldraht in the 60s to expose the East to loud sound which lead to an all-out speaker war. Both sides, with the support of the USA and Russia, were armed with loudspeaker units which would drive up and down the wall with the single goal to drown out the other side. A soundclash Jamaican style? Not so much, even though there are some formal similarities, like modern medial mechanisms, which either try to separate or bring together societies or tear down borders. That motive has played a role in my work for a very long time but becomes even more apparent within the context of German history.

The Mantis is your latest work out of a series of soundsystem sculptures. How have the technical setups developed?

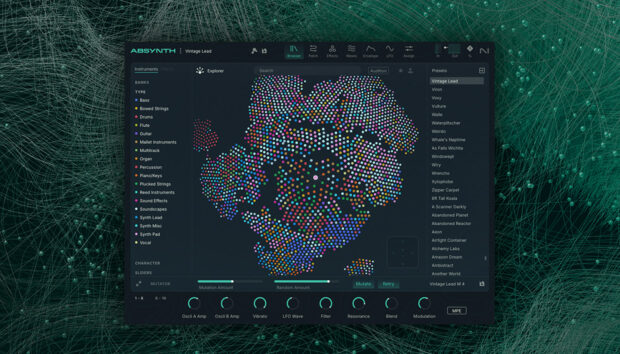

The Soundpanzer was my first large-format, full range soundsystem, and it took around four years to build. In the beginning, the performance setup was basically my studio equipment: an MPC1000, a Roland SP303 Sampler, a Mixer and a Kaoss Pad. Later, I added a Roland SP555 Sampler, an iPad with Traktor DJ and at some point I had something like a fan of stands attached to the Panzer. When Native approached me a few years ago I replaced the samplers with a Maschine, which simplified my setup a lot. For the project Schockglatze we worked with Maschine and the Traktor Kontrol S8, while the Stems format gave us many new possibilities when playing live. For my own projects, I only worked with the S8, since four decks plus Remix sets and Stems are absolutely sufficient for my performances.

The development of The Mantis took just about as long, but it is way more complex, more efficient and elaborate. Since the structure is more skeleton-like, I have less space for instruments. But when it comes to mixing, I get by perfectly fine with a reduced set up, that’s why I work with Traktor DJ 2 on iPad and the new S2 controller.

photo credits: Kensfotos

additional info:http://niknowak.de/