Rhythm is the foundation upon which music builds its cadence, inviting listeners to move, feel, and connect on a visceral level. It’s the heartbeat of music, dictating its flow and structure. Melodies and accompaniment are also built on rhythm, and these create a sense of groove as they interact with each other. The types of rhythm in music can drive emotions, influencing the mood and energy of a piece, whether through syncopation, steady beats, or more complex patterns.

In this blog, we’ll explore the basics of rhythm in music and its importance in the music you create.

Jump to these sections:

- What is rhythm in music?

- Basics of rhythm:

- Do we always need drums to have a groove?

- Rhythm in songwriting and composition

Follow along with Komplete Start, a free collection of instruments, synths, samples, and more to help you practice music theory concepts in your DAW.

What is rhythm in music?

Rhythm in music refers to how sounds take place in relation to time. Notes can repeat evenly, create patterns, be predictable or completely irregular, and not follow any specific order. Silence also takes a big role in defining music’s rhythm since it creates space between sounds, therefore becoming a rhythmic contributor.

When we look at this closer, we realize that music is rhythm. Rhythm means how things happen in time, and music is a temporal art. Unlike painting or photography, where the art is hanging still for the viewer to contemplate freely, at their own pace, music is, by nature, always moving and dissolving as it happens. We are continuously listening to the memory of sound, and rhythm is our memory of time. Perhaps we could say rhythm is our memory of the perception of time.

When we hold down a chord on a piano and then release it, we create two points in time: the moment when the sound starts and the moment when the sound ends. This is the most basic manifestation of rhythm. Any music event is attached to a place in time in our memory.

If we then follow with a different chord and release it after the same duration, we will create a sense of pulse. As listeners and music makers, we use any cues we are given at the beginning of a piece of music to create a sense of time and/or pulse in our minds.

Sometimes, there is a constant sensation of a pulsating click underneath the music. Sometimes, that pulse is not so obvious, and the timing of things can feel less regimented. Still, no matter if there is a constant understated heartbeat to the music or just events that happen seemingly randomly (or not in a predictable way), we are always in the presence of rhythm.

Now, let’s go ahead and break down some concepts that are fundamental to our music-making, keeping rhythm in mind.

Basics of rhythm

1. Beat or pulse

The pulse (or beat) refers to a constant unit of time that guides our sense of time on a piece of music. This doesn’t necessarily mean that we will have a continuous ticking or repeated note playing over the music, but more of an implied ticking clock that guides us to keep time as we play the different parts.

This is what the “click track” embodies. When we are recording and want to keep a perfect alignment to a “grid” (an imaginary time map where we place musical events), we use an audible click as a reference point to keep us in time from a machine-made source, which could be a DAW, or an electronic rhythm machine, or perhaps a good old-fashioned standalone metronome.

But, ultimately, the beat or pulse or “click” is meant to be just an imaginary abstract guide that is not heard but rather felt.

You might be familiar with the word beat referring to the whole rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment that goes underneath the vocal melody or top line in a song. Indeed, nowadays, when people refer to “the beat,” they are usually referring to a full set of elements that together create the distinct groove and main chord progression in a song. This is most common in genres where the structures tend to be constructed over looping sections that repeat over time.

But in the more traditional and elementary use of the word, beat can refer simply to the pulse of a piece of music.

2. Tempo

Tempo means “time” in Italian, but for music, it actually means speed. We say, “The tempo or BPM (beats per minute) of this piece is such.” Or “At what tempo are we going to play it this time?” in a band or live setting, referring to how fast the music will be performed.

Tempo is an exact and objective quality. And it helps us put rhythm in a context of duration to a scale. We can play the same rhythm at a different tempo, resulting in a much longer or shorter piece.

Let’s take a listen to these two radically different versions of “Billie Jean” – the original album version by Michael Jackson and the acoustic, stripped-down bluesy ballad rendition by Chris Cornell.

The original tempo is around 114 BPM, and the meter is 4/4. It’s upbeat and danceable – very Michael. Chris Cornell decided to bring the tempo down quite a bit and change the meter, creating a 6/8-type feel. All of this together creates a completely different atmosphere and adds a whole new layer of emotion and meaning to the song.

It’s hard to say what inspired Chris to come up with this approach and if the tempo or meter change came first, but I am sure one certainly influenced the other. Likely, this was all done intuitively, as most things happen in music and art. But it’s interesting to look back at it and try to figure out how or why things happened.

This could be a great exercise and experiment. Take any song you love and know well and change the tempo drastically. See how that feels once you play it at the new tempo for a while. Then, this will inspire other changes to the version. Let the music speak for itself and take you places. If we listen, the music usually takes us to the right place.

3. Meter

We use the concept of meter as a way to organize rhythm. In Western music, how we feel the strong and weak beats of the music is tightly related to the change of chords in a piece of music. We tend to feel arrival points of chord progressions to places of rest as strong beats and the chords that are less stable and more transitory as weaker beats.

Depending on how often these chord changes happen in relation to the pulse, we organize the music under different types of meters.

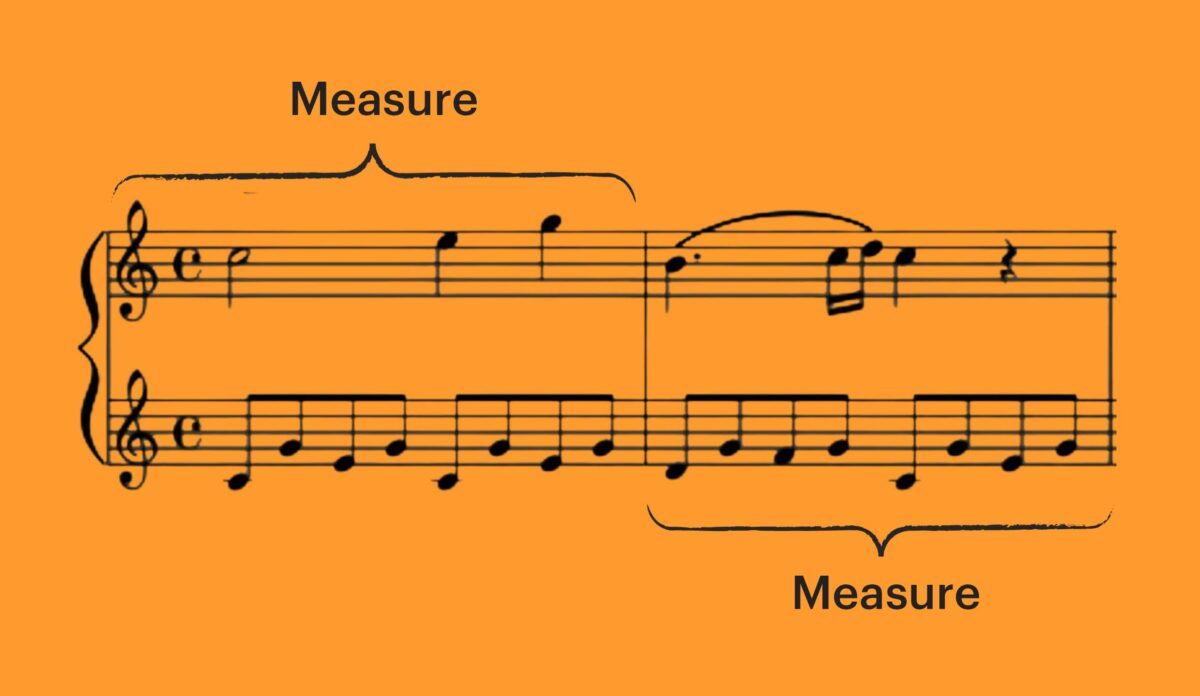

The main things to keep in mind when we think of meter are how many beats are on each measure and how each one of these beats is subdivided inside.

Simple meter

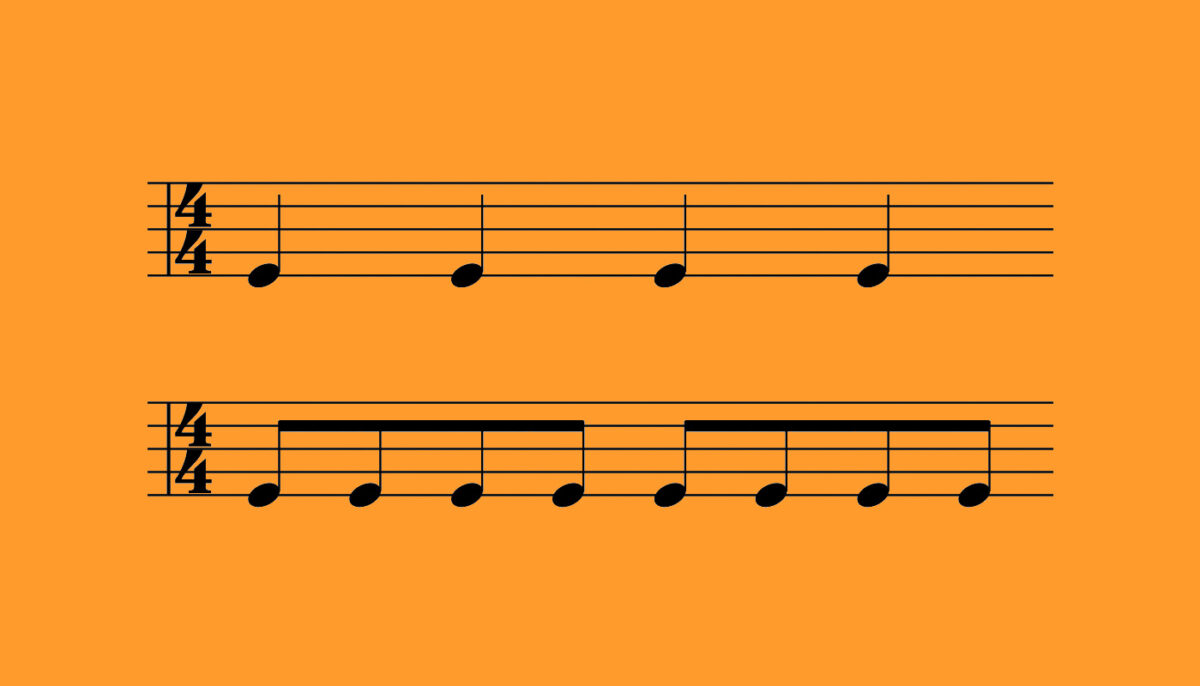

For instance, in a 4/4 meter (the most commonly found in pop, rock, and many modern genres), there are four4 beats per measure, divided inside by multiples of two2. We can have eight8 subdivisions inside a measure or even 16 subdivisions. A good thing to listen for is how the hi-hat plays the inner parts of a rhythm in a drumbeat, which usually sets the groove and flow of the whole pattern.

Just to pick one out of millions, here is Green Day’s “When I Come Around” as an example of rhythm in music in 4/4 meter. In this case, if we listen to the intro of the song, it starts with its distinct distorted guitar riff for one measure, and then the drums join playing quartet notes on the hi-hat during the second measure, setting the listener to feel a slow 4/4 with 2 measure-long phrases.

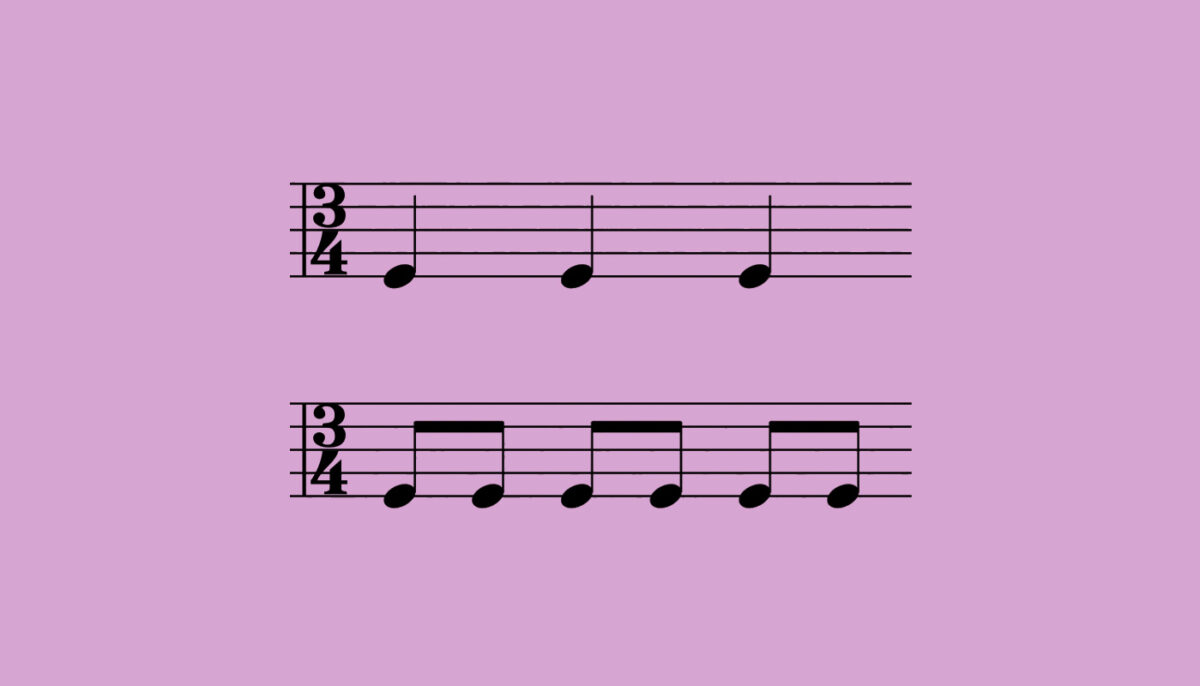

Another common scenario is to find a 3/4 meter, where there will be three beats per measure, and these will also be subdivided by multiples of two within. Waltzes are a typical example of this. But there are all sorts of songs that are written “in 3” in pop music. There is a certain bounciness to the 3/4 meter that is quite unique.

The most common place to find 3/4 meter is in waltzes. Here is one of the most famous ones from the French romantic Frederic Chopin. In this case, you’ll hear (and see) clearly on the score how the left-hand sets the rhythm with one low note on beat one, and then two higher notes on beats two and three.

Compound meter

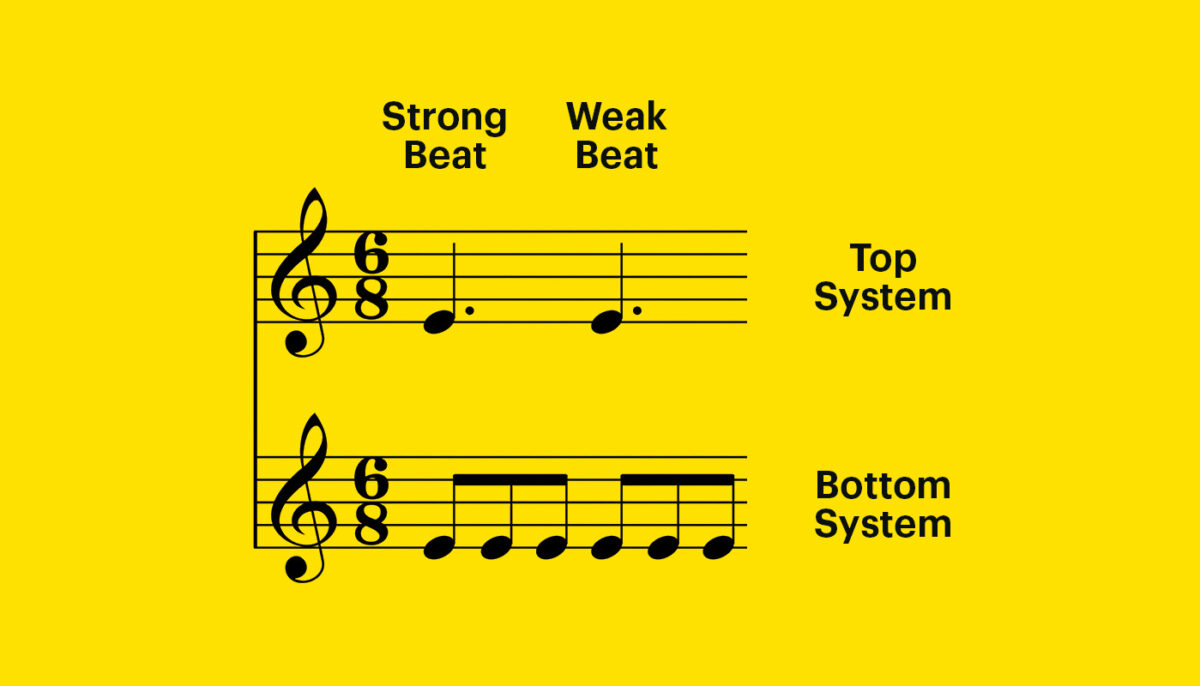

In compound meters, each beat is subdivided by three, and to differentiate it from simple meters, the fraction states the total amount of subdivisions inside a measure. For example, in a 9/8 meter, this accounts for nine total subdivisions, which are grouped in three beats.

A good example of a 6/8 meter is the song by The Beatles, “Norwegian Wood,” from their album Rubber Soul. Here, listen for the subdivision of the guitar strumming, which goes along with the vocal melody. Those are the 8th notes shown on the bottom system of the sheet music above. Now, listen to the bass notes. The long notes it plays divide the measure in two, corresponding to the dotted quarter notes on the top system. The first long note feels strong and is a place of landing, while the second note (or faster notes) feels more like a “pick-up” to the next measure. We call that “pick-up” a “weak beat.”

4. Measures

A measure in music typically is the smallest musical unit that holds a start and an end and then a reset at the next beginning. We use measures because we tend to think and feel music in chunks. These more manageable portions of music are what we call phrases, which usually comprise multiple measures. We can have fast phrases within a measure, but usually, a musical phrase fits within a couple of measures, and we account for each measure as a manageable unit of time that we can feel.

Imagine you are taking a walk around the block and are breathing at a normal pace. Perhaps we are walking, taking four steps for every breath, and that feels like a breathing/walking cycle in itself. Every step could equate to every beat in a song, and the speed at which we walk is comparable to the tempo. Once we start walking, sometimes we speed up or slow down, but we tend to lock into a groove. It’s just a human thing. That’s our natural tempo.

If we consider every breathing cycle a measure, as we look around and we pass a house, and then the following one, then a tree we see as we approach the next part of the block, each one of these sites is comparable to a musical phrase. It might take several blocks to reach our destination, and we see a lot of things as we walk. Time also passes, and we only see what is around us at each step of the way, yet we hold in memory all our journey since we ventured into our walk. As we keep walking, we keep track of the distance walked, and we anticipate what’s coming, both in time and space.

It’s important to think in terms of time and space. Or better put, accounting for space is much more tangible than accounting for time. In music, we are only dealing with time, but if we imagine we are also moving in space as we listen or play, we can develop a much more robust sense of time and rhythm. I like to take walks and listen to music sometimes. Once you become aware of it, it’s nearly impossible not to walk at the song’s tempo or at some subdivision of it. If you haven’t done it, I encourage you to try it out.

Do we always need drums to have a groove?

When we think of groove, we almost instantly think of drums. Perhaps drums and bass together as a unit. But what if I told you that the groove is made up of all the elements that provide rhythm at a given time? The drums might be the most iconic instrument we associate with a sense of rhythm and groove, but in reality, even a vocal part can help create a sense of groove.

What I am trying to point out here is that there is a distinction between percussion or percussive sounds and rhythm itself. Almost all instruments are able to become percussive (pointy and precise in time), but of course, there are some that are more naturally conducive to that, such as drums, shakers, and so forth. But, for instance, the piano is also technically considered a percussion instrument since its mechanism consists of hammers hitting the strings.

With this in mind, try to think outside the box and consider any and all elements and instruments in a song as participants in the rhythm building.

Sometimes, as I work on a production and listen back (always listen, and listen without doing and looking) to the track in progress, I try to identify what bits might be interfering with the sense of rhythm as a whole, and more often than not, it’s not the drums that need to be nudged but rather the surrounding elements. Perhaps there’s a guitar that started getting ahead half-measure before a drum tom fill, making the drum fill feel late, although, in reality, it is not the drum that needs to be tweaked but the guitar instead.

It is not always that easy to solve these situations or to identify what element needs to be worked on. A good way to tackle this is by muting a few of the elements in a mix until the problem disappears. Then, it becomes easier to know what elements are not grooving so well.

Rhythm in songwriting and composition

As a songwriter myself, I tend to start writing songs on the piano or guitar by finding chord changes with a certain rhythmic feel that then inspires melodies and lyrics. This can also happen the other way around, where a lyric with a certain cadence (the rhythm of how words flow) will inspire a chordal accompaniment, and then the rhythm of the chord strumming will be determined by the melody (top line).

Something that I find myself a prisoner of sometimes is to play the chords at the same places where the melody plays rhythmically. For example, if there is a melody with a syncopated part, the piano or guitar chords will hit right when that happens since there is such an intuitive draw to the melodic rhythm, and also, it might be harder to disassociate hands and voice to play chords and singing-melody separately.

In typical folk or pop songs where there is a constant rhythmic pattern in a guitar strum, that rhythm becomes second nature, and once it’s internalized, it’s easier to move more freely on top of it with a singing melody.

If we want to create a big anticipation in a certain section of a song, where a melody might be playing a note before the following bar, we can have the whole band hit that note with a new chord altogether, anticipating the next bar. We can also choose to play the chord on the downbeat and let the melody anticipate by itself, which will create a softer effect.

In these two examples we can hear both options. First, in the Oasis classic “Wonderwall,” the guitar strum uses a pattern that hints at the anticipated vocal melody on each phrase, “attacking” each chord at the same time as the vocal melody.

Then, if we take Ryan Adam’s “La Cienaga Just Smiled,” from his breakthrough album Gold, we can hear a constant 16th note guitar strum that keeps time and the bass and piano striking chords on every downbeat, while the vocal melody anticipates the beginning of each bar. In this case, the band and the top line are not hitting the changes together, and this creates a different kind of effect.

There is no right or wrong way to place accompaniment rhythmically. But it is important to be aware of the possibilities and use our ears and taste to choose what feels good.

Infuse your songwriting with rhythm

As we learned, rhythm is always present in music. Sometimes in subtle ways and sometimes as bold and explicit as a drum set playing the backbeat of a song. No matter what kind of music we are making or the instrument we are using, rhythm is always there, and the more we are aware of it, the more freedom we will have and the more impactful our music will be. Always consider all the elements that are present in a song and try to listen to the combined rhythmic effect of the whole band.

Remember, it’s not always on the drums or bass where you will find the most important rhythmic aspects of a piece. It could be on the piano, the guitar, the strings, or any other element. Listen and breathe the music as it moves in time and space. Keep creating and fine-tuning your sense of time on every project or song you hear.

You can practice incorporating rhythm into your music with Komplete Start, a free bundle of instruments, sounds, and more inspire your creations.