Bound by a fearless curiosity for sound design and experimentation, composer and location audio engineer Surachai explores the extremities of metal music through a modular lens. Native Instruments has long played a key guiding role; evolving his sonic aesthetic via a combination of software sound libraries and virtual environments.

A prolific producer of extreme experimental music, Los Angeles-based Surachai’s repertoire of releases pivot between the brutality of black metal and the ominous drones of the dark ambient genre. Working as a location sound engineer draws him to the immediacy of MASSIVE and KONTAKT, utilizing the combination of sampled instruments and software synthesizer plug-ins.

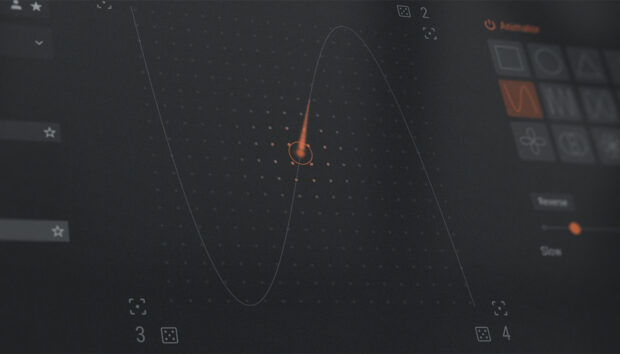

Meanwhile, REAKTOR and ABSYNTH have been key learning tools, guiding his path towards increasingly cutting-edge, noise-based output.

Surachai co-founded the Trash Audio sound design workspace as a platform to share his interest with others, joined by Nine Inch Nails keyboardist Alessandro Cortini and Richard Devine. Meanwhile, on his latest release, Come, Deathless, the producer implores himself to plumb new emotional depths. Collaborating with Aaron Harris (Isis) and keyboardist Joey Karam (The Locust), he creates sprawling organisms of noise from live excerpts and field recordings, entwined in a devastating mesh of analog synths and digital manipulation.

A need to experiment

Pop music is heavily curated and there are a lot of hands in the pot, whereas experimental music is often created by one person and more of a statement than a collective conversation. You can use presets that people relate to or mangle them up and create your own thing. Perhaps that’s what makes me experimental – I’m using the same tools that pop people are using but going through a different lens. I’m quite insulated, and most of the artists I know seem to have an idea they want to flesh out or an itch to scratch.

I’ve been doing this since I was 12 years old with hacked software people gave me. I learned stuff at school, but it was more about how to use Pro Tools or Logic, or a new thing coming out called Ableton! What I consider studying is what I did in my own time based on the curiosity I had for sound. If have you have the drive, you can learn a lot more than anybody telling you how to use something.

How I interpret sound design

When I’m making music, I never think about the listener – I don’t even think it’s going to leave my computer. The messiness you hear in my sound is the opposite of sterile, which is not necessarily a bad word. What I consider sterile is when people use modular and don’t give a shit about the mix or aren’t paying attention to the dynamics or EQ; it’s just layer upon layer of stuff.

If you listen to any of the tracks on my album and turn off the signal chain, it would sound completely unusable. It’s only once you activate the compressors and EQs that it morphs into what it is. I use processors as instruments because it’s about the dynamics and making the music breathe – like an organism. If what I do was created in a laboratory, it would be slop. I like that murkiness and the shape-shifting dynamic of it.

Location audio

There’s too much control in the studio and my current job allows me to do a lot of location audio. I’ve been to a lot of major cities, deserts and forests and bring shotgun microphones and other specialized mics that I can sync in case something interesting occurs. Location audio is a reactionary field, because you hear a lot of great sounds but they’re muffled by sound pollution.

When it comes to sound design, you can’t really recreate location audio stuff. You can probably generate noise or sample things, strip out the noise floor and re-synthesis it with RX, but when you’re in the jungles of Thailand after it’s rained at night and you hear a thousand frogs calling, there’s something very special about that.

Without wanting to give away a trade secret, there’s a microphone that can record up to 100,000 Hz, and when you start pitching it down you expose things you might not have focused on or heard. When you record animals and do experiments with the source material, you can start turning them into instruments – it all goes back to that sterile/organic or emotional/swamp metaphor.

New isn’t always better

I disagree about a lot of the new gear coming out these days being more impressive or better than whatever came out 15 years ago. It may be more stable or ergonomic, but better sonically? I think it’s more about workflow than sonic quality. For Come, Deathless, I’m mostly using the Nord Modular G2, which is 20 years old and digital, yet it still slays a lot of the software coming out now. I also use Metaphysical Function from the Reaktor User Library as a standalone thing. That’s not new at all but still sounds better than a lot of gear today.

‘Come, Deathless’ collaboration

Growing up, I’d listen to Aaron Harris’ post-metal band Isis a lot. The drumming was fundamental to my outlook. He’s a composer now, making horror/thriller film trailers and creating sound banks, so I gave him the skeleton of a track from Come, Deathless and let him do his thing, then focused on his composer aesthetic and destroyed his drumming.

As for Joey Karam of The Locust, when I heard that stuff it was like, “people can physically do this?” I thought his sound could only be done from a single mind on a computer, not four dudes all on the same level. I had no heroes growing up. Aphex Twin was cool, but you never saw him with a keyboard jamming out, whereas Joey made keyboards cool to me – I actually got visual audio.

We did a lot of file swapping and it wasn’t my place to critique what Aaron and Joey gave back to me. I was just honored for them to take an approach to what I was doing.

Conception of a track

The conception point is a lot simpler than people make it out to be. I’m usually just tinkering around going in different directions. Every element and sound I add is leading me down an aesthetic path. After 30 minutes or an hour, I’ll have something worth recording. Yes, there’s a bunch of technical stuff involved in that process, but the journey is nothing more than a series of stylistic choices, whether it be the sounds you’re choosing or the patterns you’re putting them into.

I try to work with sequencers that are fighting against me, then looking for unexpected surprises. If you’re working with an 808, you know what you’re going to get and it’s quite uninspiring, but with modular – especially the Nord Modular, and some of the software I use, it takes you in a completely different direction.

There’s a full track on the album that’s just me setting a bunch of shit up and pressing play, and there are elements of that throughout the entire recording. On one track, I set up all the sounds and let the sequencer do a bunch of randomization – or percentages of randomization – in a way that was self-generating. Then I’d curate it and just let it go.

Working with modular

The modular thing is funny to me. I’ve been using them for close to 15 years, when there were just a few systems compared to what’s going on now, but I feel its hit a plateau. Nobody seems to be pushing the envelope, except for a few modular guys and companies like Native Instruments.

I can work with any source audio, as long as it has the right dynamics processing and mixing/EQ capabilities. The only thing I never use is filters, which is strange. Of course I care about the sound and it needs to be clean, but then I work dirty so it doesn’t really matter what I’m feeding these machines because I’ll have them grind everything up and shape the entire thing.

I’ll use an 808 and put it through all these machines to create a monster, but when you turn off the machines what’s left sounds like a really dull, unmixed sound – and you might ask why the hi-hat is by far the loudest thing!

Growing up with Native Instruments

Using Native Instruments opened up a world of sonic possibilities. Hardware can do all sorts of things and hit the mark within their own vocabulary, but when ABSYNTH and REAKTOR came along, it was like, “what’s happening?” Yes, this is a synthesizer, but the potential is literally limitless.

That’s what NI taught me growing up, that these product architectures are guiding you somewhere else. I mean you can basically make any sound with any synth, but the creator has crafted an architecture that makes you think like they think – you can’t necessarily re-route things that are semi or fully hard wired. But with NI you could suddenly tear things apart or create stuff from scratch.

You also have KONTAKT or MASSIVE with a million banks of presets that you can tweak according to whatever you’re working on. For a lot of working composers or musicians, the turnaround times mean you don’t need months to do things. It’s about what you have to hand, and one of your answers better be Native Instruments.

REAKTOR – An essential learning tool

For the new album, I used a bunch of REAKTOR effects ensembles. I have REAKTOR BLOCKS too, but then I also own a modular synthesizer. If you don’t have the money to buy the hardware, I think REAKTOR is an essential learning tool and an invaluable resource to experiment with. I wouldn’t say it replicates a modular setup because there’s lots of stuff in the virtual environment that you can’t do in the real world. Some people want to knock REAKTOR, but I don’t think they know how to use it [laughs] – they’re probably not seeing the potential.

In love with ABSYNTH

I’m using Native Instruments more now in my compositional process. For my everyday job, I’ll use it for the easy stuff, using KONTAKT and MASSIVE libraries to pull stuff out and do things really fast. For my own recordings, I’m still stuck on ABSYNTH – it’s one of my true loves in life. There’s a sonic quality to it that’s fundamentally gorgeous and I can relate to at a deeper level. With ABSYNTH you can hold a key, apply pressure and listen to a sound evolve – it’s an entire story of sound and you’re creating structures. If you have the time, it’s the place to spend it.

I’m also in love with REAKTOR’s Metaphysical Function. Sometimes I’ll leave that thing on, hit random, record the whole thing and splice up the session for sound design. I’ll also do the same thing with Scapes’ Twisted Tools. I love those environments where there’s a percentage for the random button and you can just go for hours. It helps you realize the potential of the instrument very quickly and how it can shift parameters.

Conveying the creative process

There’s no right answer. I think a lot of people intellectualize too much about things when you should just start moving. People make it more complex than it actually is. If we spoke in person, I could show you how I create a patch in five minutes, but I don’t know if that would be a help or a hindrance. If people believe what I say, they would assume that’s the only way to do something. The people I follow have a ‘sound’ and the people I admire have a ‘style’. I don’t care what they use, but how they use it.