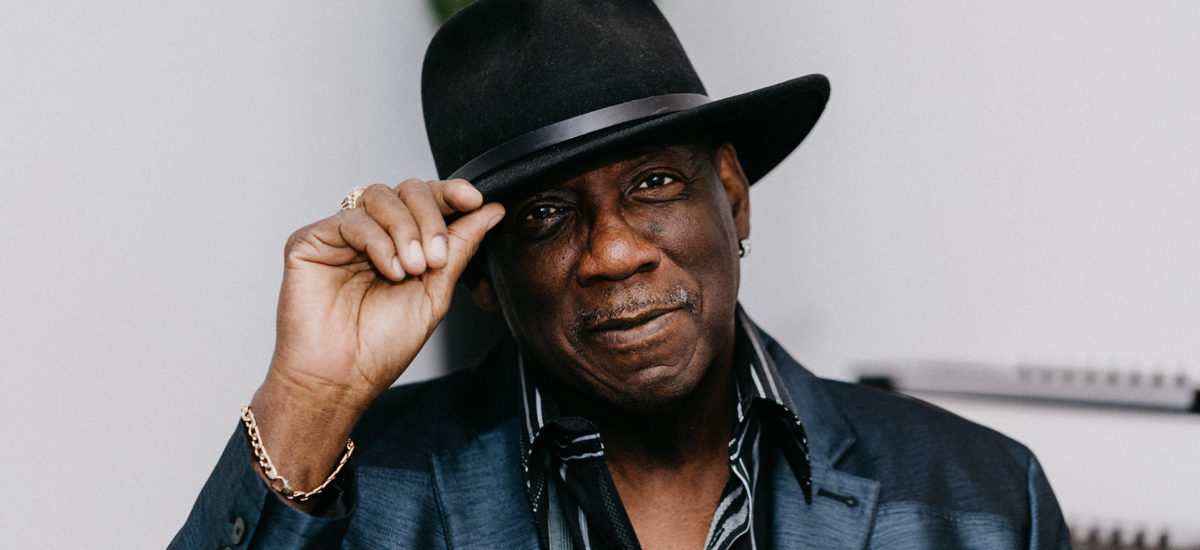

From production methods to sample licensing to streaming technologies, the past decade has been one of constant upheaval for both the music industry and the artists that work within it. As we progress into a new age of music making and distribution, few artists are as poised to carve out a space in this new world as Switch Entertainment’s Gregory Williams.

At 19 years of age, Williams was a young trumpet player when he was signed by none other than Barry White, whose own star was quickly rising in the music world. It was White that put Williams on his first record with a band called White Heat — a name that White had initially been considering for his own creative project — and started the ball rolling on what was to become an illustrious career.

Shortly thereafter, Williams put the pieces and artists together for what was to become the seminal band Switch — a name drawn from the members’ abilities to switch between different lead vocals and instruments during a song. After a chance run-in with Jermaine Jackson in an elevator, Switch was signed to Motown Records in 1976. The band became a consistent presence on the R&B charts throughout the late 1970s. On Motown between 1977 and 1983, they recorded five albums — two of which went platinum, and three of which went gold, totaling more than eight million record sales.

After a period of intense productivity, Switch took a long hiatus, and Williams went on to work as a producer, pianist, and songwriter, with the likes of Dr. Dre, Boyz II Men, TLC, and El DeBarge, among many others. In recent years, and with rapt attention from a new generation of fans, Switch reunited, featuring the original members — Williams, Eddie Fluellen, Phillip Ingram, and guitarist Michael McGloiry — along with a new lead vocalist, Akili Nickson.

With a brand new album and International tour planned for later this year, things are starting to heat up once again for the band. Williams has also gathered his experiences in the music industry into a book, titled Switch, DeBarge, Motown & Me!. Finally, through his own Switch Entertainment Collection publishing arm, Williams has created several new sample and loop products for Sounds.com, as well as an R&B/funk-inspired artist collection. We spoke to him about all the action bubbling up in 2019.

You can check out Gregory Williams’ Sounds.com Artist collection here, or go to the Switch Entertainment sounds collection here.

Switch has undergone quite a revival in recent years. To what do you attribute all the newfound attention?

There’s been a worldwide resurgence of old school music, based on the fact that current music does not have the substance and quality of the music we did back then — I’m talking late 70s, 80s, even early 90s. The marketplace was looking for substance and quality, and there’s been a resurgence in old school R&B. A lot of acts from our era and our genre are working now, here in the US and worldwide. Fortunately, we had enough hits and built enough of a following over the years, that when we said Switch was back to work, the phone starts ringing.

Did that surprise you, or were you sorta waiting for the day?

Kinda waiting it out, to tell you the truth. I was hopeful, which is why I pulled the group back together in 2003 — hoping that things would turn around, and we could at least work and eat through our music again.

Was there a big re-learning process involved in putting together a new record?

Yeah, man. All my guys remained in music, and stayed active over the years, so everyone was still on point — but the issue was making sure I had the right lead vocalist. Because if you’re familiar with the sound of the original Switch and Bobby DeBarge as a vocalist, well, that was the hardest thing: getting someone to sound close enough to that to matter. I couldn’t sell it any other way.

Eventually, a friend of mine played a demo for me, and I found a guy who sounded like Bobby — Akili Nickson — and reached out to him. After meeting him and discussing with him, he said he’d do it. That was 2017.

How was the process of recording that album? Was it hugely different to what you’d been doing back in the 70s?

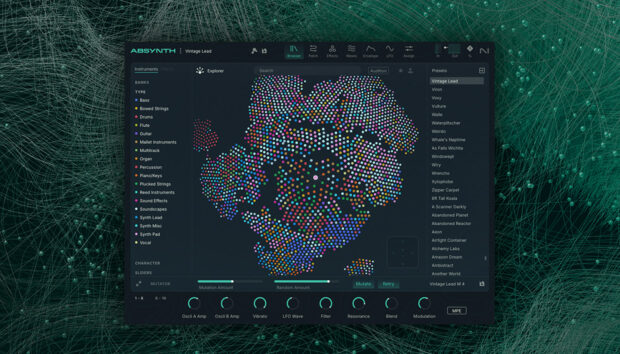

For us, no — because we went back to the tried and true. The sound of Switch now is pretty much the same as it was, just technologically up to date. A lot of these youngsters will use samples and drum machines and everything else. We went back to what we do — we’re musicians, so we went back to the music. All of us have Pro Tools and Logic, so we did the majority of it at our home studios, and then when we had it all together we took it into the studio to finish it up.

You also have several Sounds.com projects in the works.

Right now I’ve got about a dozen collections online, and me and the guys collectively are bringing even more to the table in 2019. I’ve done all kinds of projects, but this was my first sample collection. It was exciting to create loops and samples and beats. I thought it’d be a challenge, and it is [laughs] — and it’s cool.

The challenge was going from making a whole song, to a snippet or a small piece. You have to reduce your thought process, and then actually decide how it will be used — which dictates how much and what you create, ultimately.

My collection started with me reproducing Switch’s hits: “There’ll Never Be,” “I Call Your Name,” and “I Wanna Be Closer.” Reproducing the rhythm section, and then tearing it down into individual parts, and then even cutting those parts down to individual bars — which created the samples and the loops.

That’s how I started, but then I stretched out, dissecting a jazz album I’d recorded, which has quite a few components and quite a few songs. And I began to dissect that, I started coming up with guitar parts and horn licks and pianos and basses out of those recordings, to create different collections. That’s how I’ve built up to just under a thousand samples and beats and loops thus far.

You’re also working on an artist collection as well.

Yeah. What it made me do was dive into the samples and loops and beats of other contributors. I decided what I wanted to create, and listened to a whole bunch of libraries to pull the bits and pieces together. I like that process now as well, because it affords me the challenge of deeply listening to and dissecting other people’s stuff.

Had you worked with sample-based music before?

Not too much. I’m an old school analog cat. [laughs] But, if you do not reinvent yourself, you will fall off into obscurity — and I didn’t want to do that. I still have a lot to say, musically, creatively. You have to keep up and stay on top of it. I learn new technology, and I keep up.

I’m surrounded by computers, but still, they’re machinery to me — they are not the creative source. I am the creative source — I am that analog guy that has to be able to sit and play.

Funny story — back in 1978, synthesizers were just coming out. We had to buy new equipment, because our gear had been stolen. I picked up an Arp Odyssey; after signing with Motown, we lived and rehearsed in a house, rehearsing and learning songs for the new album. I’d had this thing for a month, and I barely knew how to use it — until one day this group of girls came over, and they said, “What is this? Play something for us!” And I couldn’t play a damn thing! I was so embarrassed that for the next three months I learned that thing inside and out. [laughs] A little bit of incentive goes a long way for learning new technology.