When it comes to sampled real instruments, there are so many orchestral libraries and cinematic sound generators out there that it takes a lot to make something special. You have to create something that’s curiously unique, eminently playable, and instantly inspiring, all at the same time. Fortunately, that’s the entire philosophy behind Galaxy Instruments – case in point, the latest release, NOIRE, which was created by the Galaxy team in Saal 3 of Berlin’s famous Funkhaus complex.

NOIRE recreates composer Nils Frahm’s Yamaha CFX Grand Stage piano, a nine-foot concert grand customized especially for the neo-classical pianist. This KONTAKT instrument comes in two flavors – felted and unfelted.

“I’d had an ambition for some time to sample a felted grand piano,” says Galaxy’s Uli Baronowsky. “Nils called me up about his new grand piano and we went there to listen to it. We were just standing around that piano, and he was playing without felt, and we were all so excited about even the basic sound of this piano without the felt – we decided to do both versions.

Uli and his Galaxy colleague, Stephan Lembke, sat down to tell the rest of the story.

Can you explain how a felted piano works technically, for anyone who hasn’t had the opportunity to hear one?

Stephan Lembke: Typically you have an upright piano, and you have a pedal for damping it. You have a piece of felt, and when you press the pedal, the felt gets between the hammers and the strings – the hammers hit the felt and it makes the strings a bit softer, warmer, duller. It’s more for playing at home and playing quietly, but for a grand piano, nobody wants to play quiet, so it’s not a typical grand piano thing.

Uli Baronowsky: What you get is a smoother and softer sound. The relationship between the sound itself and the noises you have is different, because – especially on an upright piano – those mechanical noises of hammer on the felt can be as loud as the ‘real’ sound of the piano, so they can serve as a musical, percussive element.

It was special to have a felt preparation on a grand piano –you usually use felt on an upright for playing at home and staying quiet, but with a grand everybody wants to play loud, so it’s a very unusual thing to see. Nils used a similar felted CFX for the soundtrack to the movie Victoria – it was the very first film music he did and right away he got the prize for Best Soundtrack!

What would you say is so special about Nils’ particular CFX? As someone who’s got to know its sound through the microscope of sampling…

Uli: It’s not a typical CFX – it’s got a very round tone. And together with that room [the Funkhaus’ Saal 3, operated by Nils himself], that sounds very special. His piano technician, Carsten Schulz, insisted on changing all the hammers and re-intonating the whole thing right before the sampling – and with that, the sound changed a lot. Nils popped in and played it for the first time after that, and he was really excited about the way it sounded.

It’s been recorded with Nils’ microphone setup, too. We had a whole bunch of microphones standing around, and we had a couple of mixes, but we ended up with pretty much his mix, including room mics. It’s his preamps as well, so there’s a lot of ‘Frahm’ in it.

By now, you’ve modeled a huge number of instruments. You were responsible for most of the other pianos within KOMPLETE, too. How long have you been doing this, and how did Galaxy Instruments get going in the first place?

Uli: It was around 2006. I was working as an engineer and I was booked a couple of times for sampling sessions. We had one session at Galaxy Studios, sampling a Steinway D in 5.1 surround. With the producer, I made a deal to re-use a lot of the samples to make a virtual instrument. That was the first step, and it was followed by a couple of other pianos of our own.

Stephan: I came to work with Uli over ten years ago as well. I started editing samples, and helping out during recording sessions. I was involved with recording The Giant, and then we started doing the Definitive Pianos sessions.

Uli: I was talking to Native Instruments about Kontakt, as we were building things for the platform, and they asked me about doing a sampling project together. At that time we’d already recorded The Giant without knowing what to do with it.

Stephan: The idea wasn’t to approach anyone with it – it was more about just recording a cool instrument… in fact we had to record it because they were selling the building!

Uli: From then on, it was just about ideas. For Rise & Hit, when doing regular music production, I’d always missed something for easily implementing a riser with a hit, and we started brainstorming about how we could do that. That was the first time we did something with an orchestra, and it was a great experience. Then the idea for Thrill came up.

Stephan: There are always some sounds that trigger you. You hear them and it sounds really cool. When we recorded Thrill, we had a whole low woodwinds section playing a cluster – it’s amazing. But we don’t want to repeat ourselves – we’re looking around and thinking about new ways to find something interesting.

You must have learned a lot about making better sampled instruments with each passing experience.

Uli: Our methods are developing all the time, starting with simple things like the number of velocity zones, which now is 22, while the first ones had ten. This instrument in particular has a very wide range of tonal color – from very soft to very bright – which makes more velocity zones necessary.

What’s different from the very beginning is the way we implement piano resonance – when you press the sustain pedal and all the strings can resonate. That also developed from instrument to instrument: We recorded more and more resonances for different cases, just to try to get it as realistic as possible.

When we did The Giant, which was located here in Germany in an old piano museum, the room wasn’t that great, but we couldn’t move it. There was no way to move that oversized upright piano, and so we really started concentrating on the room. For Una Corda, we found the perfect one: That was our first time in Saal 3. We got to concentrate on the room and the equipment around it.

NOIRE’s definitely not only about capturing an exquisite sound. What are the features that make it more than just a piano?

Uli: This time we developed something we call Tonal Shift, which actually goes back to the story of a Beatles recording [In My Life]. George Martin played the solo and couldn’t play it fast enough, so they pitched down the tape machine to half speed, and pitched it up again for playback. It changed the sound so that it was almost like a harpsichord.

Now we have this knob, and you can use it in both directions. It shifts the tonal spectrum either from a regular piano to a harpsichord, or the other way around, which makes it softer.

There’s also a feature in Noire called the Sub, with which you can simply add a sub bass. When we listened to the piano the very first time, Nils had some pickups placed on the low strings, which went to his PA speakers.

Stephan: The PA was in the same room, and we were so surprised when he played the bass – it was way more bass than we’ve ever heard from any grand piano in any room.

The Particles Engine seems like a really inspirational way to push the virtual piano forward – the best of digital combined with the best of real recordings…

Uli: The very first idea behind the Particles Engine was to just press the sustain pedal and, in a soft way, just play in octaves, giving you some sort of piano pad. We decided it didn’t make sense to record it that way, so decided to script it… and then it kept on developing.

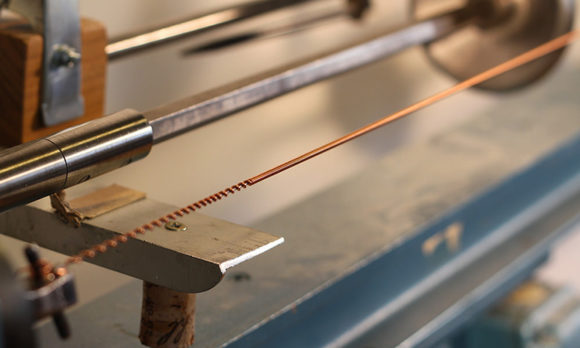

When you get repetitions or octaves from the Particles Engine, every note, or ‘particle’, creates a different sound, and the timbre changes all the time. We recorded that CFX with different articulations, we had felt plucks, wood plucks, different mallets, brushed versions and stuff like that. When we tried the Particles Engine out with the brush sounds and plucks, it was a new world of sound.

We added more and more algorithms, we allowed it to sync to the host tempo, and from then on we could create a rhythmic bed or a sequence – you can set certain key points and use it as a aleatoric tool, creating notes randomly.

It sounds like a big departure from the traditional instrument…

Stephan: Sound is a big part of it – having repetitions and having the option to shape that sound; being able to only take the particle engine-generated sounds and putting them through a reverb, a big delay, and making the cloud fit together even more.

Uli: You can change the Attack to get more of a pad sound – as they’re aleatoric, based on a random engine, they change all the time.

Uli: Every preset is completely different, and it’s really an inspiring tool because it depends on what it does – you simply play differently. You play something, the particles Engine reacts in an aleatoric way, and then you react to the Particles Engine. You play something which you didn’t expect you would have played. It’s inspired by the type of music Nils plays.