Born in Eutin, Germany, soundtrack composer Anne-Kathrin Dern’s career has been incredibly varied, working on everything from animation to video games, including large studio productions like Ocean’s 8, Geostorm and the family comedy Help, I Shrunk My Friends.

Having studied at the private film scoring academy Musicube, Dern went on to complete a Bachelor’s in Film Scoring in the Netherlands at UCLA. Despite harboring a long-held ambition to work as composer for film and TV, she first became involved in developing virtual instruments and digital samples for Cinesamples, a creator of orchestral sample libraries (some of which you’ll find in NI’s NKS store).

“I really wanted to work in film and TV and Hollywood Scoring [Cinesamples’ sister company] was located inside the studio complex of composer Christopher Lennertz,” she explains. “I’d done a couple of mockups as part of Hollywood Scoring for him and New York film composer Alan Menken, when they started working on a TV show for Disney and asked if I wanted to be part of the team for both seasons. I basically handed in my two weeks’ notice and switched rooms, writing additional music for Chris and Alan.”

While Dern continued to sporadically work for other sample developers, she also assisted high-profile composers including Steve Jablonsky, William Ross, and Pinar Toprak, and interned with the legendary Hans Zimmer through his film score company Remote Control Productions.

“I was waiting for my immigration paperwork to come through and there was a back-log so I couldn’t leave the country or work for money at the time,” she recounts. “That’s when Steve Jablonsky’s assistant said he could get me into Hans Zimmer’s studio to do a free internship. Remote Control’s such a great place because you have 200 people working there and can make a lot of connections by default. To do an internship there is kind of a rite of passage, but I only interacted with Hans rather than worked directly with him – unless you count making coffee. I guess I fuelled his caffeine habit [laughs]. When I came out of that I was almost immediately contacted by Klaus Badelt who asked me to start writing for him and that was the turning point in my career.”

A myth that’s been perpetuated is that every score is done by, in Dern’s words, “one genius mastermind,” but that’s almost never the case – it’ all driven by team work. “In today’s productions where we have less and less time to complete the job, there are so many different processes involved, especially with orchestral live recording, which becomes a completely different beast when you’re interacting with at least a hundred people. Through Klaus Badelt my own connections started to pay off and I had enough work and high enough budgets to warrant setting up my own studio and hiring people in, especially as I didn’t always quite know how to complete those projects by myself.”

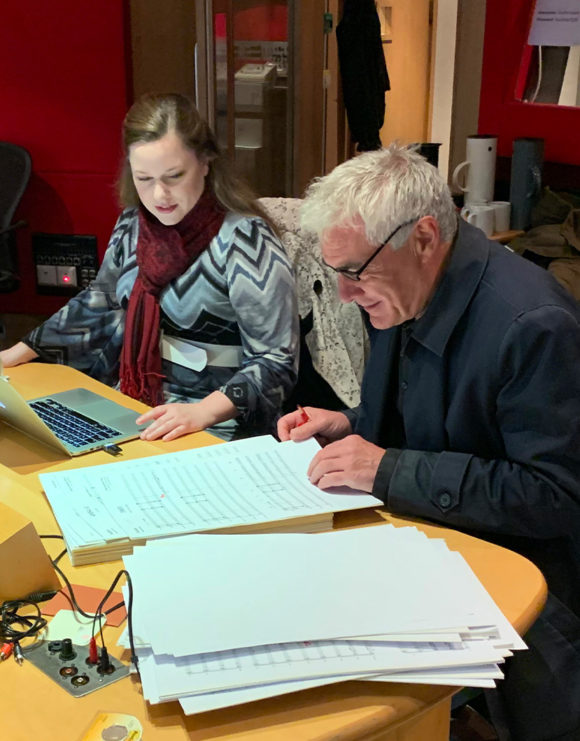

Indeed, several elements of film scoring are commonly outsourced so the composer can focus on the writing itself. For example, many composers prefer not to make their own orchestral mockups – here, Dern is the exception: “Personally, I love doing mockups so won’t give that away, but that does mean I need to get additional writers in. On each project I write thematic material, get that approved by the production team and end up with this elaborate Google Sheet. Then I give away all the small scenes to my team members because I know I won’t have enough time to do them myself. I’ll brief them on how to do the scene and what instruments to use so they can take over and create these little 10- or 20-second cues while I focus on the big opening scenes, battles, and big emotional cues.”

Later in her career, Dern would go on to create e-Quality Music Productions. The LA-based studio is today focussed on the composition and production of music for film, TV, and video games. As implied by the name, Dern is committed to increasing the diversity of Hollywood’s scoring scene, including a commitment to maintaining a 50/50 gender split in the studio’s music department.

“I was just trying to create educational material and internship spots for people who could really benefit from working on my productions,” she says of founding the studio. “I’m also part of a forum and a discord server where previous assistants can get together and talk about assistant culture in Hollywood, which can get very toxic. We founded a group and made a handbook about fair working conditions and the red flags to watch out for because we always felt that our main mistake was not being educated enough to know what to ask for.”

Elsewhere in Hollywood, film studios are beginning to provide initiatives for under-represented groups and agents are actively trying to diversify their rosters, but there remains a system in place that’s struggling to change gears. This is particularly true of the older, bigger studios, yet Dern remains optimistic for the future. “I’ve been talking to executives from Netflix about how much they’re pushing the envelope in bringing more diversity in front of and behind the camera. They have the advantage of being a very young company so can make things up as they go along and invent their own rules rather than play by anything that’s been in place for the past 100 years. I always compare it to software that’s been around for 20-30 years and using a very old source code that’s very difficult to adapt to new technology.”

Over the past couple of years, Dern has extended her mentoring activities by creating her own YouTube channel to further educate and inspire up-and-coming composers. ”I started to make some YouTube videos and people asked me to keep doing that, so here I am little over a year later creating free resources for people to learn from. I think it’s important this information is out there because education in the US is incredibly expensive and that closes the door for so many people. A lot of internships are unpaid and I disagree that you should need a lot of money to get into this business. We’re just trying to level the playing field a little bit.”

Returning to Dern’s work for sample library developers, she first discovered Native Instruments’ Kontakt in 2007 – not long after she first started studying. “I knew a little about MIDI but not much about how samplers worked and there was basically a requirement in school to learn certain tools. Kontakt was one of them because all the sample libraries on the market at the time were loaded into that sampler so there was no way not to learn it. Even now, it’s the most common player that developers use. That’s how I learned about Kontakt, but coming out of my studies at UCLA, one of my first jobs at Cinesamples was making instruments for them. That’s how I started learning how to make these instruments from the ground up, which encompassed pre-production, recording, editing, looping, and tuning.”

Dern’s work saw her involved in every stage of creating a new library. “I didn’t know a lot about it until I did it, but it was basically a masterclass in how to create orchestral virtual instruments, and there was naturally some overlap with Native Instrument’s offices because we were releasing our products through them. I had to take a real deep dive into Kontakt’s scripting and back-end engine in order to develop these products.”

“One of the main libraries I worked with at Cinesamples was Cinestrings. We booked the Sony scoring stage with studio players from LA and sound engineer Dennis Sands would record it all. We’d set up all the microphone positions and do a live mix as if it was a real recording session, but instead of recording real pieces we’d just record snippets of instruments, so you’ll have the players playing staccatos, sustains and legatos in different velocities, which takes many, many days.”

Once the samples were recorded from each instrument section, Dern would take them back to the office for further processing and importing into Kontakt “For the programming, someone has to write a script for the instrument to work and it basically takes several months to play around with these instruments until they work as intended. Then we send them off to Native Instruments to get packaged, encrypted and licensed.”

With so much choice available, how do software libraries manage to create an element of differentiation that’s distinctive from the competition? “It depends on the library, but with the string libraries the edge here was that we had the Sony scoring stage with actual Hollywood players and Dennis Sands. It’s kind of like another sampler library creator recording all of their stuff at AIR or Abbey Road. Making orchestral libraries sound super-original is not really the goal. Unless you intend to make extended articulations, the goal is to make a really good-sounding, playable orchestral library right out of the box. We did get more creative with our Tina Guo Acoustic Cello Legato package. She’s a very famous cellist who’s worked with Hans Zimmer, and we sampled her electric cello and did some more interesting stuff with the engine by playing around with the sounds and being a lot more creative.”

Today, Dern’s DAW template is filled entirely with Kontakt instruments, and it doesn’t seem like that’s going to change anytime soon. “It’s still the most efficient player and the one that most developers will lease into. It just has certain functionalities that other players are still missing, and while I have hundreds of instruments loaded inside my template from different developers, Kontakt is the thread that keeps everything together. It’s one of the few players that are resource-efficient and multi-timbral, so it can load several instruments at the same time in one instance, and that’s really helpful – otherwise everything can start to become cluttered and difficult to use.”

Being a composer that’s so familiar with the design of custom virtual instruments, Dern is naturally curious about how audio production software might develop in the future, and has some ideas of her own. “I can make a two-minute cue in the morning within two hours, but it will take another eight to do the mockup, so the bulk of that work really needs to be cut short. I’d love to see specific samplers, sample library companies and DAWs working together to figure out a faster way of doing this. One thing that should be possible – and is coming up in sample modelling – is for an engine to detect what articulation you’ll be playing by default instead of having to tell it what something was. Or, eventually being able to just write sheet music in notation software, import that and have your DAW’s Kontakt instruments create the mockup from your sheet music. Basically, I’d like to see more AI-based stuff take over a lot of the things that we have to do manually.”

For an invaluable source of tutorials, reviews, interviews, and industry insights, be sure to subscribe to Anne-Kathrin Dern’s YouTube channel. You can also keep up with her latest projects at annedern-filmcomposer.com.