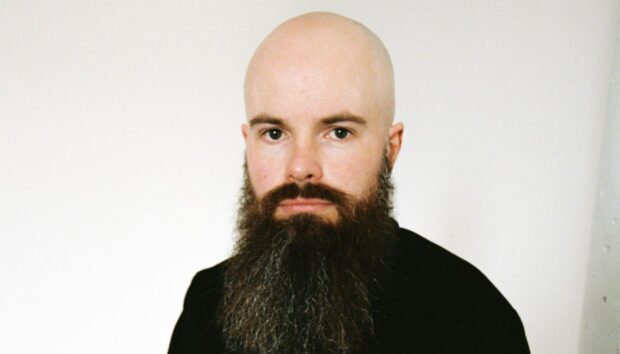

Dylan Wissing’s drumming career has had an interesting arc, from relentlessly touring with ska-influenced band Johnny Socko to recording with some of the biggest names in pop music. Wissing is best known for his epic drums on Alicia Keys’ Grammy-winning hit ‘Girl on Fire,’ and has also appeared on records with Drake, Kanye West, Eminem and Jay-Z.

A self-described drum nerd, Wissing has been building an impressive library of drum hits and loops — much of which is now available to Sounds.com subscribers — as well an equally exhaustive library of actual, physical drums. His collection of literally hundreds of kicks, snares and toms has (mostly) survived a hurricane (Irene, for those keeping score at home), and several floods; and good thing, as Wissing’s exacting approach to sampling those drums has become a boon to producers.

Native Instruments spoke to Wissing about his work on Yeezus, the importance of simplicity in pop composition, and the creative time-travel of drum recreation.

Check out Dylan Wissing’s drum collcetions over at Sounds.com here.

How did you first get started making music?

So, my great grandfather was a drummer in the circus and vaudeville, back in the teens, ‘20s, and ‘30s. He was a songwriter as well — he actually had some hits back in the day. So yeah, that’s kind of always been in the family. When I was a baby, apparently my favorite thing to do was to pull out the pots and pans in the kitchen and bang on them with wooden spoons — not much has changed, really, I just have access to better-sounding pots and pans.

I grew up in the middle of nowhere in southern Indiana, and just had drums — no neighbors and no TV, but lots of vinyl, as my parents had a pretty wide-ranging record collection. So I just got kind of obsessed with listening to records, and trying to figure out what stuff was — I had no clue back then, I just heard the sounds and would get in really deep. Jazz, a lot of the ’60s R&B, a lot of way-out ‘70s cosmic jazz stuff. For some reason my parents — and this is definitely an oddity in the backwoods hills of southern Indiana — had a lot of Sun Ra records. Which was cool.

I did the school band thing, and got really turned on to playing drums. One of my first teachers was the session drummer Kenny Aronoff: he’s one of the world’s top rock drummers, and has been for decades now, and was friends with my parents. In first grade was the first time I was ever in an actual recording studio, and I’ve just been kind of obsessed ever since. I later studied with Shawn Pelton, and through all that had a sort of aborted career as a jazz studies major for a little while.

In 1990 I formed a band called Johnny Socko, and we spent the next 13 years touring the country. I was kind of a ska/funk/punk thing, highly influenced by Fishbone, and we just sort of did it in the trenches for 13 years — just, you know, put the band in a van and traveled around the country playing a couple hundred shows a year — for 13 years. We definitely got our mileage in.

How did you make the transition from touring to studio drummer? Stylistically, Johnny Socko is obviously pretty far from Jay-Z and Kanye.

The last Johnny Socko record was produced by Ken Lewis, and he’s just a huge resource for recording, producing, writing, and everything else. When I moved out to Hoboken, New Jersey, I became his session drummer, and was doing a lot of work at his place — just kind of learning everything I possibly could about how to record, how do studio work, how to build your own studio. Early on, my first huge, crushing disappointment was that I was just about to play on Jay-Z’s “Black Album”, and then found out that they had double-booked drummers, so I didn’t end up on the record.

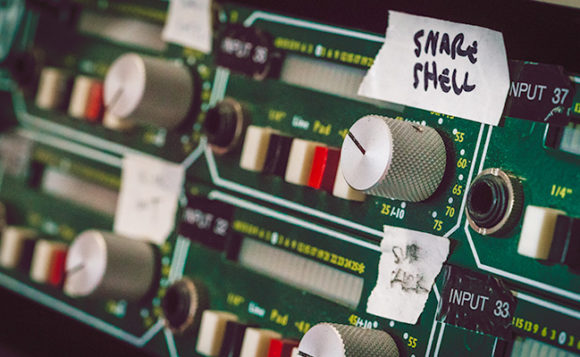

I did a lot of sample recreations with Ken, and man, I can’t tell you how much that taught me about how to dive deep into drum sounds, tunings — a million and one obsessive details of how to make some drum today sound like some recording from 1972. We’d have to go into just crazy, crazy amounts of detail to figure out how to reverse engineer this stuff, which honestly I absolutely love.

It can be really stressful work. I worked on Yeezus for Kanye, and we did drum tracks on a Monday night, and we were working all night, and then the next day Ken put together and recorded a gospel choir — all without sleeping — and somehow the record was in stores that Saturday. I always kinda felt like Victor the Cleaner from “La Femme Nikita.”

Is that when you started amassing your drum collection?

Yeah, because of that I’ve ended up with, you know, 50 snare drums, and 20 bass drums, and I don’t know how many toms — whatever the sound is, I need to be able to do it right now. My specialty has never been manipulating other pre-existing samples — it’s making new ones. The stuff that has to feel human, and often in really quirky ways.

How did you make the transition from studio drumming to sample pack creation?

It was a very organic outgrowth. For so much of my recording work, people say, ‘Hey…can you give me this 1975 sound or that 1968 sound?’ I’d put a kit together that sounded like it was from 1975. And it was a lot of work, and I’d think, ‘I wish I could share this with the world.’ So I was really happy to see the Sounds platform emerge, which is a really cool place to share this stuff.

I definitely play on records that sound like “today” as well, so I don’y always have to be a sort of ‘70s drummer, but my heart is always in analog drumming and real humans playing it.

You’re a bit of an outlier in that sense — it’s a bit like doing practical effects in the film industry.

Yeah. I want to actually build the Millennium Falcon and be able to walk through it, instead of creating it purely out of pixels.

Do you do much digital work on the samples after recording?

I’m a really average amateur mixer. I work very closely with my production partner Tomás Shannon, who does the mixing for my loops and makes the demo tracks. He’s worked with me for years, and he’s great. So I’m sort of generating the raw materials; my job is to get the sounds right, the mics right, send those raw materials out Tomás, and he does the final mixing and editing.

What’s the process like for recording drums that you’re going to be using for a sample pack, versus recording for a specific artist or record?

Well, a good recent example is I just put together a big kit of drums from 1976. I bought the kit from a drummer who had passed away, and was in one of the famous Jersey Shore doo-wop bands back in the ‘70s. It really hadn’t been touched since the ‘80s or something, and you know, you’d hit it and immediately — ‘that’s the sound of 1976’. They just can’t sound modern, no matter what you do to them.

So yeah, it sounded like every shitty, early ’70s cop show that I saw on TV when I was a kid. And that was it — I was like, ‘That’s that’s my next sample pack, because the sounds are right here.’

So it’s really not any different for me from working with an artist who says, ‘Hey, I have a song I’m working on and here’s my reference track — can you make it sound like this?’ I’ve had, for example, a few different clients independently say, ‘Hey, could you give me something like the White Stripes meets Kanye?’ And I’m like okay — so what would that be? “Seven Nation Army” and “Black Skinhead” together, or something — this drum, tuned this way, with these mics, hit this way with this kind of muffling in the room. And I’m kinda off to the races from there.

They’re both matters of deconstructing ideas back to their roots, sonically.

Yeah. And another big thing that I always put into these packs — if it’s even remotely appropriate — is the percussion. With so many of these old records, such a big part of that drum sound is the tambourine on top of the kick, or someone playing maracas with overdubbed congas, or whatever. So if I’m going to work on a song and I wanted to use the “Impeach the President” breakbeat, what would work on it? Well, gotta have tambourine here, vibraslap would be cool on this one — that kinda thing.

It sounds like you’re spending a lot more time in the home studio these days.

The one thing I’m not doing so much these days is tour. I used to tour a lot, and then I had a child and just decided I didn’t want to be gone all the time. So that’s really when I just focused on getting my studio up, and running and getting that really happening, which has turned out well. Every week is always different; I’m never sure what it’s going to look like. Some weeks I play live shows with a few different artists locally in New York and New Jersey, and some weeks there’ll be a lot of recording — the past couple of weeks have been nonstop recording.

It sounds like you’ve carved out a nice niche for yourself.

The reality is everybody can do absolutely everything on their laptop — except record live drums. I can’t tell you how many songs I’ve cut where the song’s done and the artist has done everything themselves, and they got sick of the boring, static drum loop, so I come in and replace those.

I hear a lot of drummers playing stuff that’s really focused on other drummers — here’s this complicated thing that I think other drummers will think is impressive. And I don’t necessarily know that that works if you’re trying to create a song that’s not only aimed at drummers.

The biggest song I’ve ever worked on was was “Girl on Fire” by Alicia Keys, and I think I played a grand total of six notes on it, period. And you know, it took three days of work to get those six notes exactly right, but that’s it — that’s the entire song, and it’s a huge hit. So that’s something I always try to keep in mind.

photo credits: www.dropkickjoshphoto.com

Find out more about Dylan Wissing here:

www.dylanwissing.com

www.instagram.com/dylan_wissing

http://www.youtube.com/c/DylanWissing