Breakbeats (or ‘breaks’) have been a part of electronic music since the arrival of affordable samplers in the late 1980s. But what is a breakbeat, and what is breakbeat music?

A breakbeat is part of a record where all the instruments drop out and the drums are heard solo. You’ve likely already heard some of the most famous breakbeats sampled from tracks such as “Think (About It)” by Lyn Collins, “Funky Drummer” by James Brown, and “Amen Brother” by The Winstons.

The majority of the most famous breaks come from funk and RnB tracks, but breaks can come from any genre such as rock, “When The Levee Breaks” by Led Zeppelin and pop, “Sweet Pea” by Tommy Roe.

These drum solos became known as breakbeats when the original generation of hip-hop DJs such as Kool Herc began using two turntables and two copies of a record to create extended drum workouts.

In this tutorial, we’ll show you how to make breakbeats drums with a guide to chopping breaks and tips on how to make a breakbeat drum pattern with the RHYTHM SOURCE expansion for KOMPLETE.

But first, let’s look a little deeper at the history of breakbeat music.

The history of breakbeat

In the 1980s the introduction of affordable samplers like the Ensoniq Mirage, Akai MPC60 and E-mu SP-1200 meant hip-hop producers could start sampling breaks to make records such as “I Desire” by Salt-N-Pepa. Sampled breakbeats made their way into other styles of music such as house, “Turn Up The Bass” by Tyree Cooper and techno, “E-Dancer – Velocity Funk” by Kevin “Reese” Saunderson, and became an important element of the hardcore rave sound that emerged in the early 90s.

A particular subgenre of hardcore rave, simply known as ‘breakbeat’ or ‘jungle’ like “Finest Illusion (Legal Mix)” by Foul Play made breaks the focus of the tracks, giving birth to breakbeat-ajacent genres such as drum ‘n’ bass like “Finer Things” by Wax Doctor, big beat like “Gotta Learn” by Danmass, and nu skool breaks like “777” by Aquasky Vs Masterblaster.

Use what you got

The original breakbeat-sampling OGs of the 80s would have primarily sourced their breaks from vinyl, and in the early 90s sample CDs featuring popular breakbeats began to appear. In more recent times soundware creators have begun to make their own fresh breaks that aim to recreate the feel and sound of the classics, and you can find these in expansions such as Native Instruments’ DECODED FORMS and RHYTHM SOURCE.

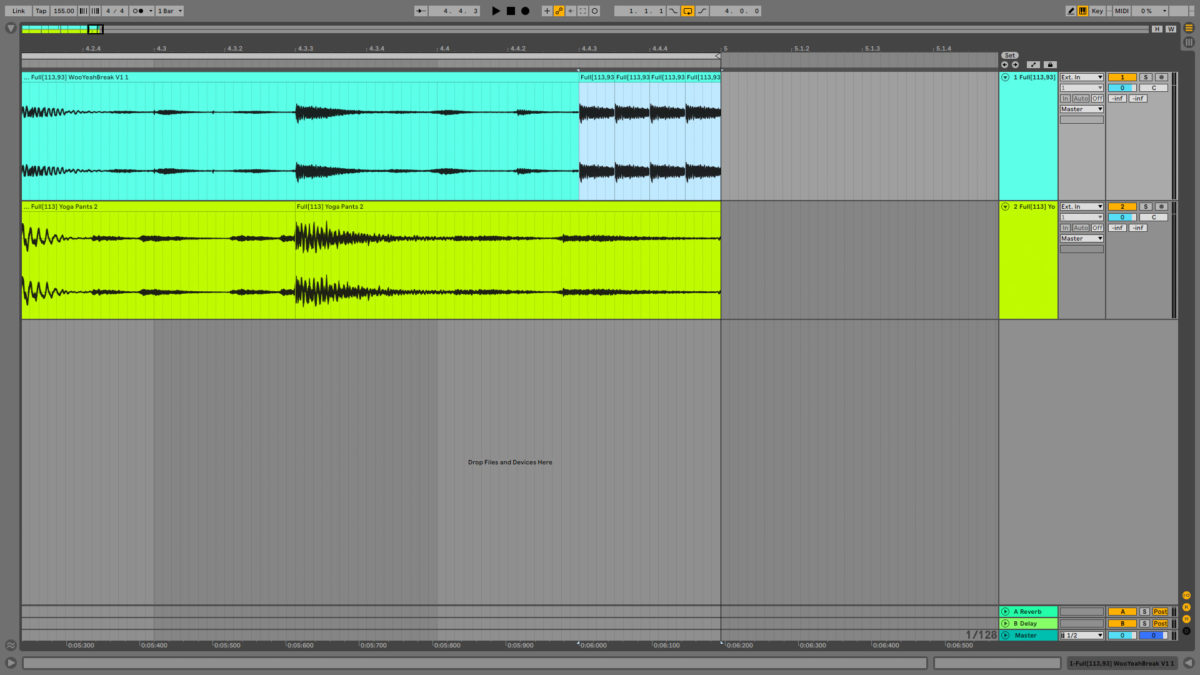

One of the great things about using breakbeats is that you don’t need any special software or plugins, in fact anything that can play back a sample will do Both Native Instruments KONTAKT and MASCHINE have advanced features that you can use to creatively process breaks, but in this tutorial we’re going to take a broader approach to looking at breaks. In fact we’re just going to use a couple of audio tracks in a DAW, specifically Ableton Live in this case.

Let’s learn how to make breakbeat-based music. You can follow along with two recreations of classic funk breakbeats from the RHYTHM SOURCE expansion.

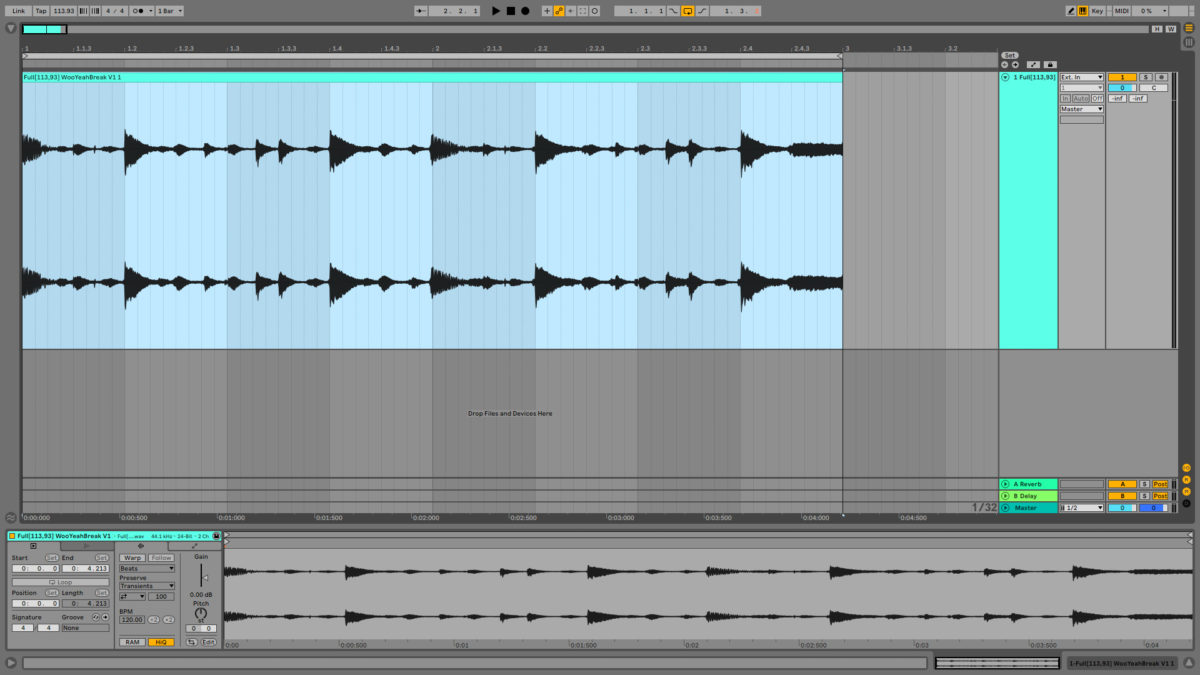

1. Load up a break and set its tempo

Let’s begin with Full[113,93] WooYeahBreak V1 1.wav. Drag this onto an audio track. You’ll notice that the filename contains the breakbeat’s tempo: 113.93 BPM. Set the project tempo to 113.93 BPM, and we can see that the break lasts for exactly two bars, and the kicks and snares sit neatly on the beats. If you want to check that the beat is in time with the project tempo you can turn on the metronome to check.

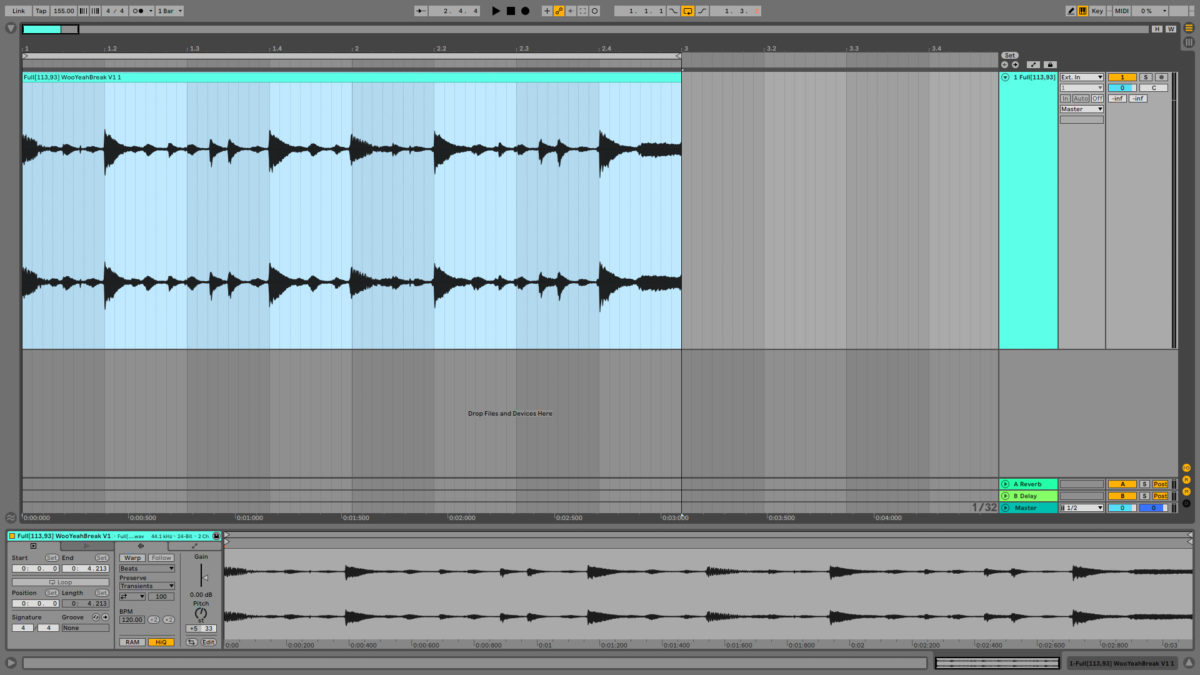

2. Re-pitch the break to a new tempo

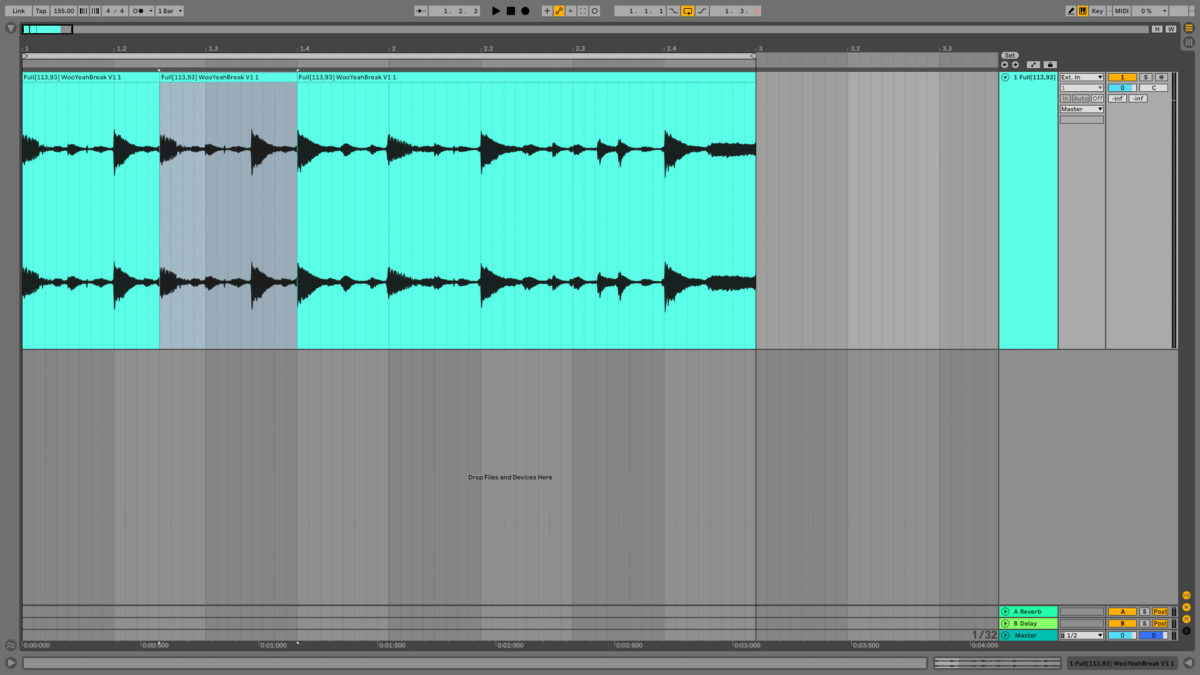

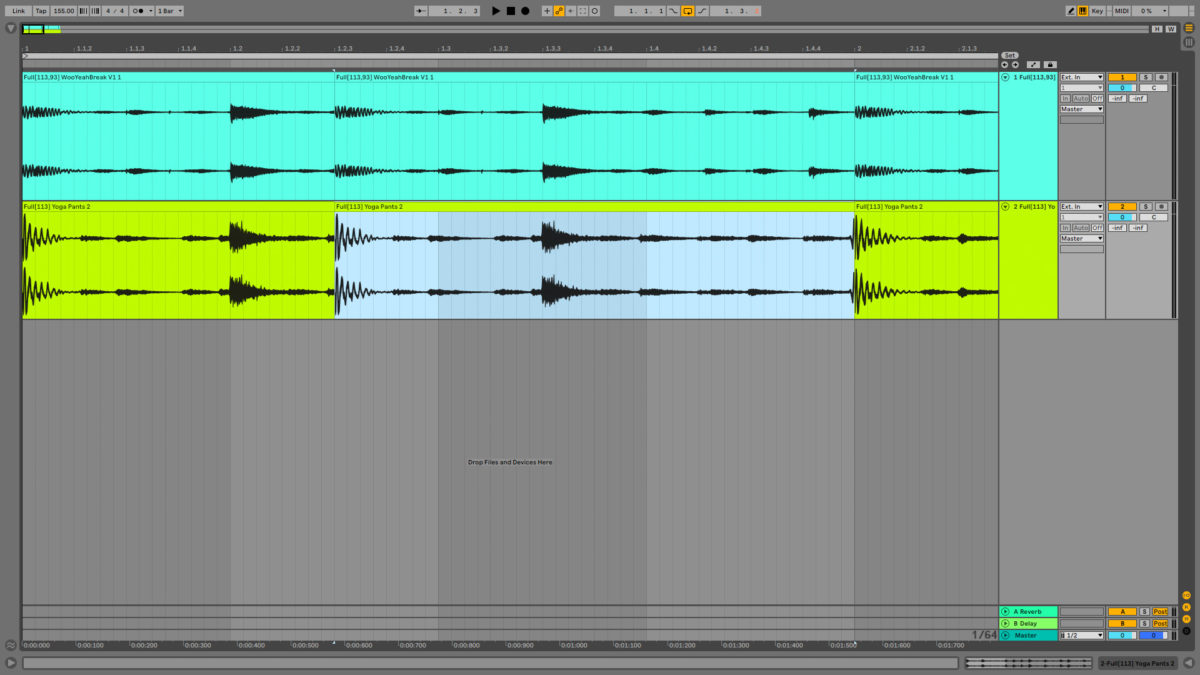

When you use breaks you’ll usually want to have them play back at a different tempo. For example, if we want to make a hardcore breakbeat tune we’ll need a faster tempo. Set your project to 155 BPM. You’ll notice that because the project tempo is faster, the break lasts for longer than two bars, and the hits don’t sit neatly on the beats as they did before.

We need to speed the break up to fit the new tempo, and we can do this by adjusting its pitch. Turn up the pitch of the audio clip until it fits to a single bar, +5 semitones +33 cents is about right. On playback, we can hear that the break is in time with the metronome, so we know we’re ready to move on to the next stage.

3. Rearrange the break

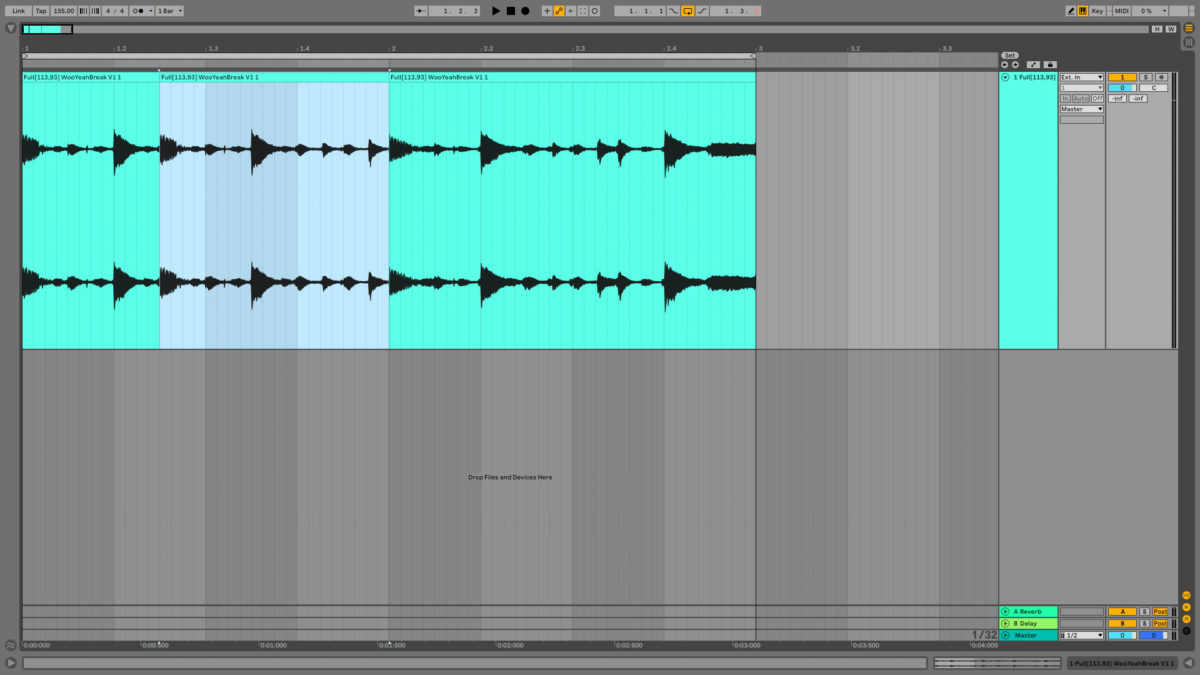

Now we’ve got our break at the new higher tempo we can try rearranging it. In Live select the first beat and a half, then hold [option] on Mac or [alt] on Windows to create a duplicate, and drag it over so that the duplicate clip starts halfway between beats two and three.

4. Keep it rolling

The pattern we have now has snares on both the 6th and 7th eighth notes, and it’s a little snare-heavy, so let’s extend the second clip out to the end of the first bar. This reintroduces the hat shuffles, and gives us a more rolling, jungle-style beat.

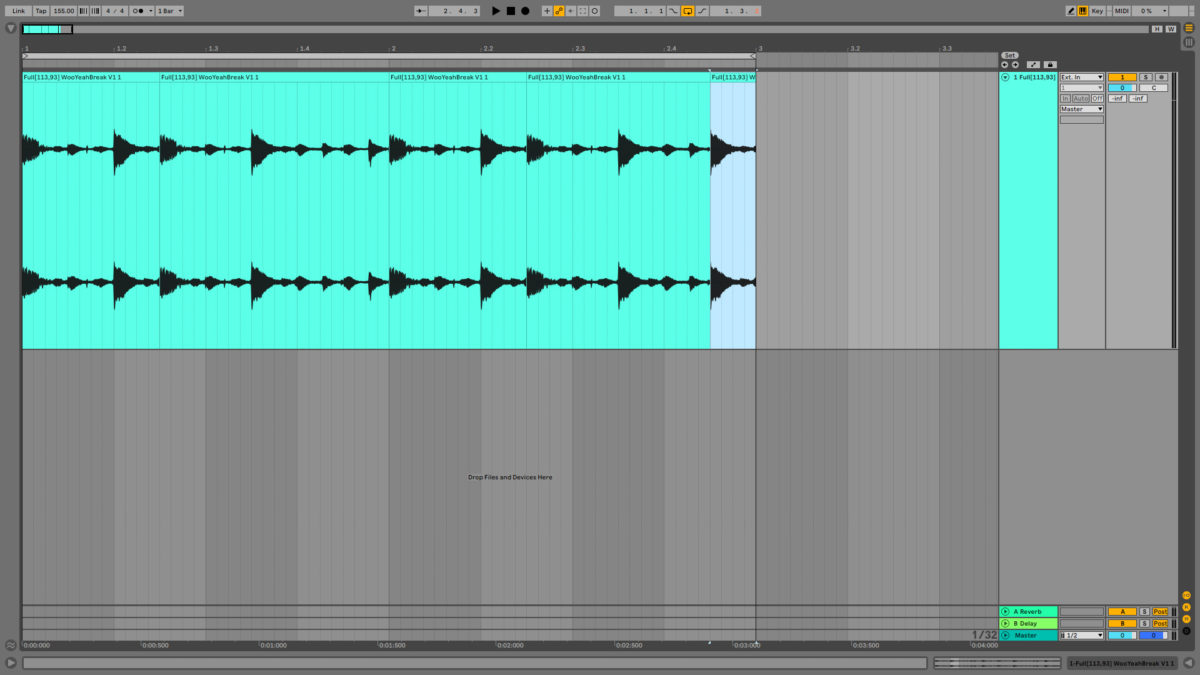

5. Add variation

Duplicate the first bar over the second bar, giving us two identical versions of the first bar. Then, duplicate the snare on the 6th eighth note of the second bar onto the final eighth note of the second bar. This gives us a cool little variation every other time the break plays.

6. Make an edit

A cool trick used by jungle producers is to change the pitch of hits to create ear-catching variations, known back in the day as ‘edits.’ Pitch the final snare up a semitone. You’ll notice this creates a gap in the audio before the start of the next bar, but don’t worry, it’s how the effect sounds that’s important, and this sounds just fine.

7. Layer another break

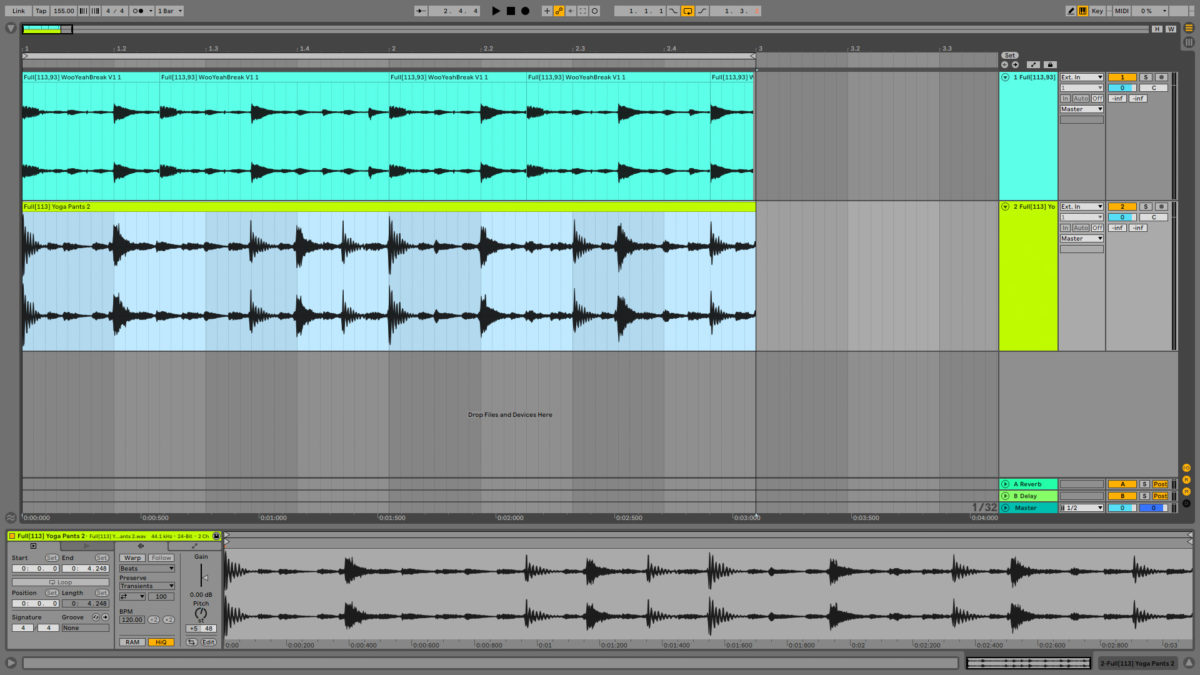

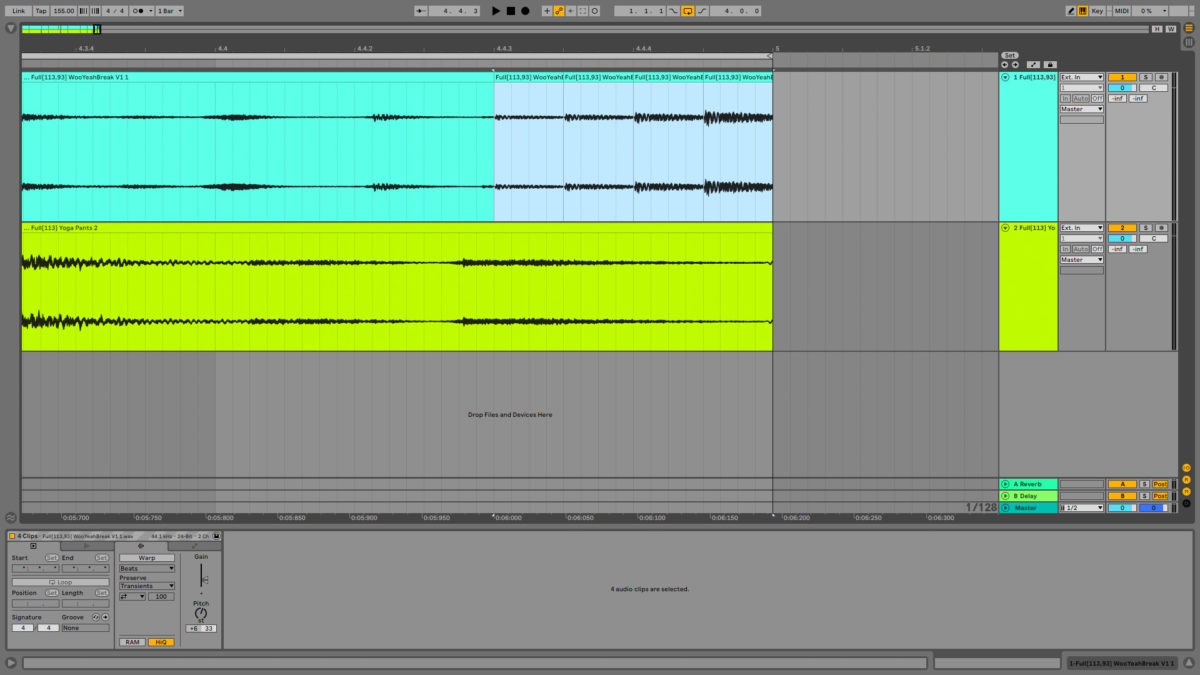

Let’s add our second breakbeat, “Full[113] Yoga Pants 2.wav”, onto a new audio track. Pitch this up to +5 semitones +48 cents, and it sounds nice and tight with the first break timing wise. However, the pattern is a little busy. Let’s try something a little more streamlined.

8. Replicate a rhythm

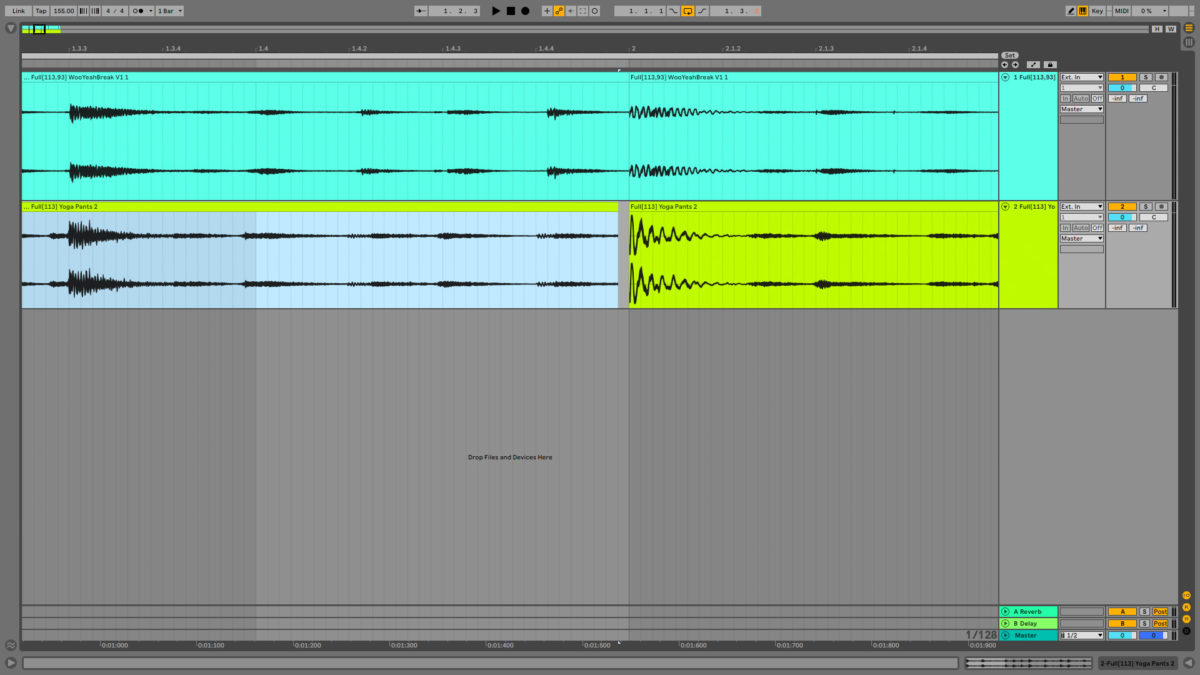

As we did before, duplicate out the first beat-and-a-half of the break, and extend it so that the break’s shakers occupy the last beat of the first bar.

You’ll notice that in this case, a kick starts playing just before the start of bar two, which makes the break sound a little messy.

9. Tidy it up

To remedy this, zoom into the end of the first bar and truncate the audio clip so we don’t get the start of the kick. Again, a gap in the audio clips doesn’t matter as long as things sound good.

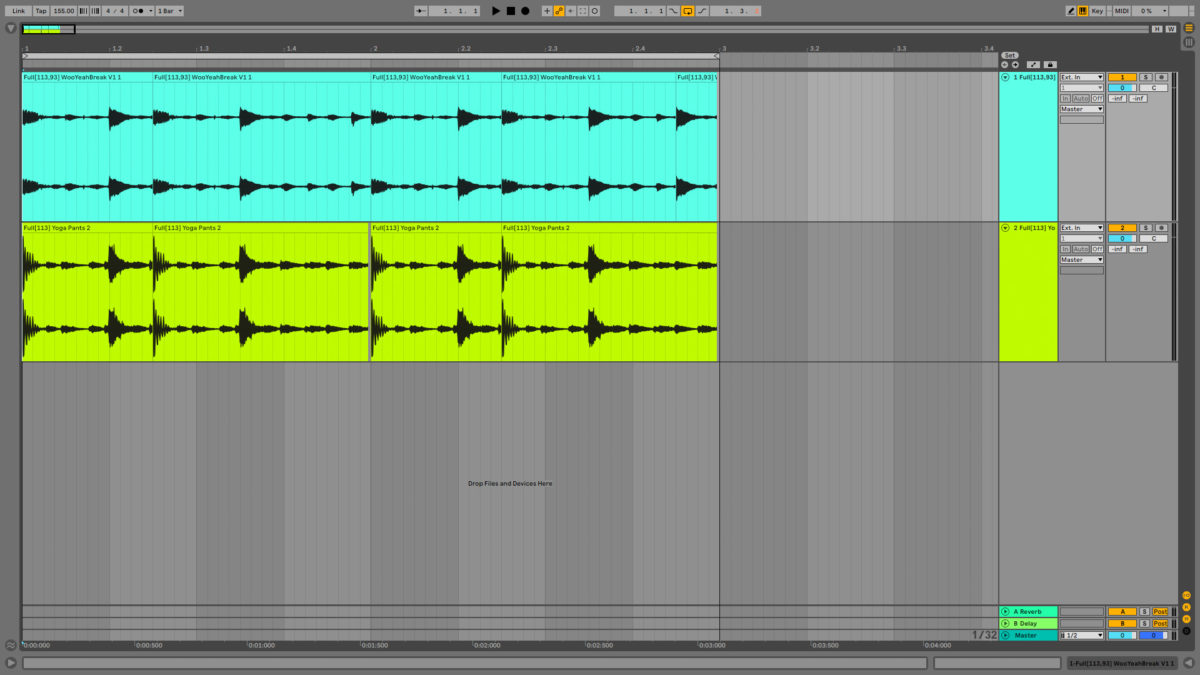

10. Make a clean two-bar groove

Now delete the second bar of the second break, and duplicate over the first bar. This gives us a clean two-bar groove. The pitched-up snare on the first break isn’t replicated on the second break, but this gives us a nice subtle variation. Next let’s make a more drastic edit.

11. Mash things up

Duplicate out both bars of both breaks to give us a four-bar groove. On the last snare of the second break, slice the audio clip, and pitch the new snare clip down an octave to -7 semitones, +48 cents.

Select and delete the excess audio after the start of bar 5. This pitched down snare section of the break gives us that classic jungle “mash-up” sound, that provides a cool variation at the end of every four bars.

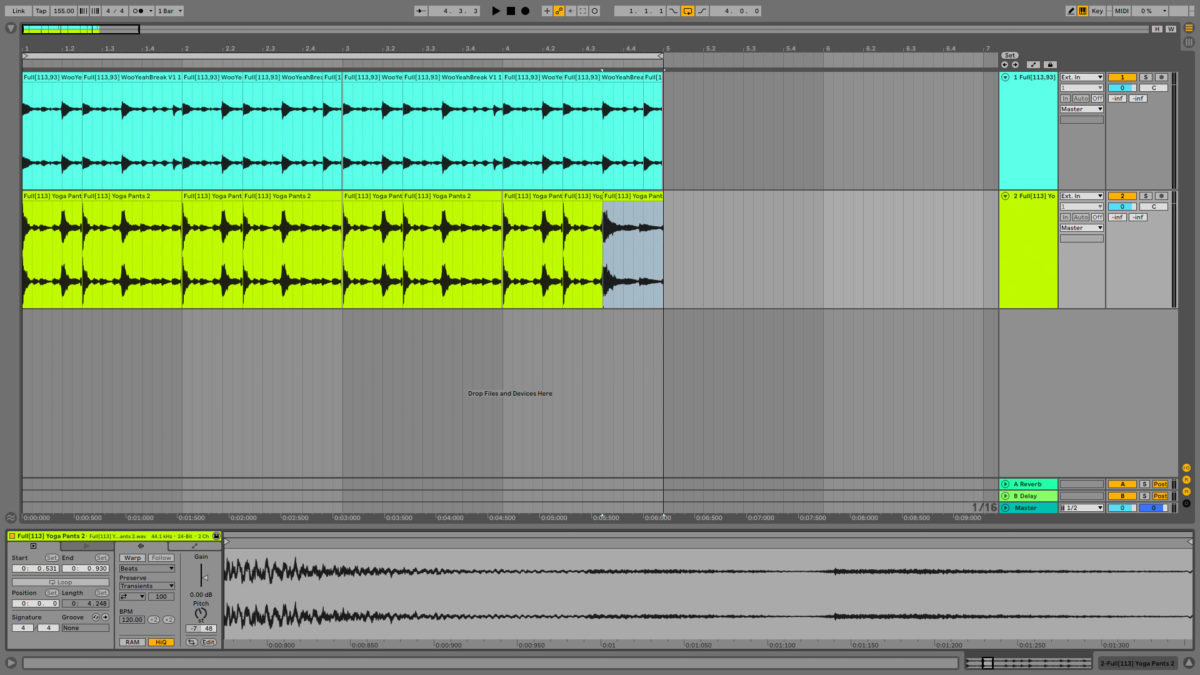

12. Roll the beats

As well as changing the pitch of notes, you can get some cool effects by adjusting their velocity. Duplicate out the start of the snare on the first break three times so that it rolls before the start of the next bar. This doesn’t sound too natural as is, but we’ll deal with that shortly.

13. Velocity variations

We want this rolling snare to start quiet and increase volume each time it plays. Set their volume levels to -12 dB, -9 dB, -6 dB and -3 dB. This gives the roll a smoother, more natural feel.

Start making breakbeat music

Now you have all the tools and skills to start making your next breakbeat. If you’d like to explore making breakbeat music further, watch this video from breakbeat techno artist Clouds on making a track with Native Instruments KOMPLETE.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history of breakbeat electronic music as well as how to make breakbeat drums, check out A Beginner’s Guide to Jungle Breakbeats.