The sampler is perhaps the newest instrument available to humans, in contrast with the human voice, which is easily the oldest. With MYSTERIA, renowned developer Galaxy Instruments finds new ways to perform, customize, and otherwise mine the world’s oldest instrument, using KONTAKT as a canvas on which to paint a wide and varied masterpiece.

From huge reverberated ensembles to hushed alien whispers – and everything, seemingly, in between – MYSTERIA provides a rich palette of sounds for musicians, sound designers, and game and film scoring. Sometimes – as in the rumbling sub frequencies, or the smooth blends of up to four different sources – it’s hard to fathom the sounds even originated from humans.

From their studio in Cologne, Germany, Galaxy Instruments’ Uli Baronowsky and Stephan Lembke shared the painstaking process behind MYSTERIA, from recording choral ensembles to blending and effecting them in KONTAKT and fine-tuning the instrument’s controls.

What was it that you were listening to that inspired Mysteria?

Uli Baronowsky: On my side it was mainly classical stuff. I mean not really classical music but [Krzysztof] Penderecki or especially [György] Ligeti, stuff like that. Because it’s not that often that you hear choral music in a soundtrack, so it was mainly inspired by those guys. And we had kind of a choir mastermind we were working together with, who was writing modern music for choirs and conducting choirs, and he came up with a lot of texture ideas which have a certain kind of emotional impact. That was my inspiration really.

Stephan Lembke: I think it was the same for me, because we were looking through all kinds of music and it was really hard to find something like this. When we were working on Thrill, we were listening to all kinds of soundtracks and television series and everything, and we found little bits and pieces of electronic sounds and orchestral clusters and stuff like this, but with Mysteria it was quite difficult to find something in a modern movie soundtrack or something.

Uli: With Thrill, you hear orchestral effects in soundtracks all over the place. And there was always a link to those modern classical composers, like in that case especially Penderecki. So if you hear stuff from Penderecki, on a lot of pieces you can simply take some part and use it in some soundtrack. So that’s the same link, there’s way less choral material in soundtracks as compared to orchestral effects stuff.

Mysteria is divided mainly into “atmospheres” and “clusters”. The atmospheres evolve from a set pitch, while the clusters can be played with different notes on keyboard. How did you decide on the separation between what worked better as an atmosphere versus as a cluster?

Stephan: It depends a bit on the technical side. For example, if you have a lot of moving pictures and they have to work together, or you have glissandi going around, then it’s hard to do that with the cluster designer in a controlled way, so that would be a perfect example for the atmosphere. Or there were some things where we had some melodies with intervals, and we did not choose to do this in the cluster designer because that would mean having a lot of other samples to fill in the gaps or create those melodies in the first place. With clusters we were limited to having a texture on one pitch, and with the atmospheres you are more free. So it mostly depends on do you have pitch variation and different intervals and stuff like this, or can it be focused on one key at a time, one pitch at a time.

Uli: Yeah, especially if you have some of those textures, either very dissonant or not that dissonant, you don’t get that aleatoric complexity if you’re using the cluster designer. Then we have certain textures or articulations, with glissandi or pitch shifting or something like that, but you always have one voice per key so if you have a whole choir aleatorically, singing glissandi or melodic bits, then it gets to complexity which you can’t simply achieve with the cluster designer or with multi-samples.

You’ve referred to some of the atmosphere as “aleatoric” – what does that mean to you when it comes to playing Mysteria as an instrument? Were you looking for a sound that is different every time you press the same key, or something that generally surprises the user, the performer?

Uli: The target is having a texture which simply sounds diffuse. And so “aleatoric“ in that case means that we had certain key points, for instance some melody bits, and then we let all the singers randomly sing those bits, and then you get those interesting but diffuse textures out of it.

Stephan: It refers more to the kind of recording we did and the performance of the choir in the session than to the instrument itself. So it’s not like having aleatoric parameters in Mysteria, such that every time you press the key you can get something totally different. Because if you are a composer, it would be a bit more complicated writing the score for a scene or something if every time you started in your DAW it sounds different. So we still want to have that control, but the performance of the choir was the aleatoric bit. On the other side, we have all those aleatoric atmospheres recorded and overlapping, and when we morph through those sounds and morph through the dynamics you have the loop points on different parts of the sample. So for example, if you just take the XY, put it to an area you like and then don’t touch it anymore and just hold the key, you can listen to it for 10 minutes and then you get the total repetition, but it still sounds organic and you don’t feel a sense of repetition.

Because it’s not one loop, it’s many different loop points for the different voices.

Stephan: Yeah, and different layers and stuff like this, so you still have some kind of aleatoric feel depending on how long you hold something.

It was, like, two months just to get the crossfade right for the XY. It was a really frustrating time.

The XY controller on Mysteria is quite brilliant. Most sampled instruments that have similar controllers for blending samples, you end up hearing where the seams are at some point. There’s a real smoothness to Mysteria though. There’s no abrupt transitions, and changes in sound seems to sneak up on you. You can go from a Hellraiser-esque set of whispers to a heavenly angelic shimmer, and not notice a particular breaking point. How did you design that kind of morphing in Kontakt?

Uli: First of all, I think it’s the combination of not only morphing or fading between two sounds on the left or the right side, but having a couple of layers on each side. So depending on where you have the XY it’s always a different combination between some layer on the left and on the right side. And developing this engine, we did that actually not with Mysteria but with Thrill, and that took months.

Stephan: Yeah I think it was, like, two months just to get the crossfade right for the XY. It was a really frustrating time.

So is that a custom script in Kontakt then?

Stephan: Yes.

Uli: I think the focus during that time was curve. Like, getting the right curves so it works smoothly. It was a long path, but I must admit that with Thrill and with Mysteria I was very happy with the result. Because it’s really smooth and you can’t really tell when it’s going into a different sample. So it’s morphing all the time in a very smooth way.

Stephan: But I think there are two areas to it. One is having the morphing on the XY between two sounds, two layers, left side and right side. I think that works so smoothly because every layer itself, or each source itself is what we have designed. And that is why we can’t really give it over to the user because we have this source editor in the sound design process, where we shape the volume curves to get smooth transitions: You have a volume curve, you can create and you can layer that, and you can crossfade it, and it is almost custom every time for each sample set. So then we basically put in the samples that we want to use and then we load up a curve set, for example crossfading with some sort of volume matching, and then we adjust it by hand just to make sure that we really have a smooth volume curve. We also use stuff like automating equalizer bands and stuff like this to get it even more smoothly and that is only for one source.

And so then if you take this source, combine it for example with another one you have the layer. And then if you take the two layers and you morph those and crossfade those, it works because they themselves don’t have any real gaps in between and things like that.

What kind of consideration did you go through when you were recording the choirs? There were choirs in Bratislava and Cologne—what consideration did you go through in terms of choosing the right room, the right microphones, the right gear to process it?

Uli: Well we went to Bratislava because we had been there for those orchestral recordings, and that’s mainly because of that room—because that studio has a big sound, simply. Because there are a lot of orchestral or choir recording studios which are simply a bit too small, you don’t get that space. That’s why we went to Bratislava and that was recorded with a lot of microphones, but it was kind of a traditional microphone setup with a Decca tree and close mics and ambient mics, plus we also had those, what’s the name again of the 100 kilohertz mics?

Stephan: Ah, 100 kilohertz mics from Sanken Audio – the CO-100k. They go up to 100kHz, so we recorded the choir at 192kHz, so we can pitch it down and then you get all those overtones that you’ve never heard before, and bring them into the audible range. Then you can use that for sound design and things like that, and it still sounds natural.

You know, if you record something at the normal rate on a tape machine and play it back slower it always sounds like a monster or the god voice or something. But with those high-resolution microphones you get the overtones we don’t hear, and if you pitch it down you still have them and so it just sounds like a very big person, without this “oh, it’s a slowed down tape” sound.

Uli: Yes, those microphones were special. And we went to Cologne because that was a different choir, and as I said that choir mastermind who was involved with this. And we knew that they were used to experimental stuff, and then we also had a great quartet who specialized in modern vocal music. We did one session with those guys and that that was…

Stephan: Eye-opening. They were singing some kind of Gregorian piece, and then it seemed like you could just tell them “could you throw in some odd notes?” and then they threw in some wrong notes but in the perfect manner, and then you could say “now do it again, but a little more” and it became even more chromatic, or even with quarter-tones and stuff like this. So it was a real pleasure working with them.

Did those become some of the aleatoric atmospheres, then?

Stephan: Yes. When you have a look at the category, there you have the “quartet” button in the main presets, and also in the browser. And if you click on the quartet then you have all the quartet ones.

Some of the “sub” presets in Mysteria have a really inhuman sound, almost like they’re impulse responses from massive caves, or a drone like you might hear in a Lustmord or Burial piece. You mentioned using the 100 KHz microphone to allow for greater pitch-shifting. How else did you design these sounds?

Stephan: There’s a lot of sound design involved as well: pitching things around, slowing things down, using pitched-down reverbs, things like that. So the human voice is a starting point for the hybrid stuff, but the hybrid sounds can almost be like a synth triggered by a voice. That would be like the extreme version, or something like the sub where you pitch it down really low, support those frequencies and then get rid of everything above just to lay the foundation.

Uli: Yeah, but I think really the basis for most of the sub sounds are the real basses from the choir, which we then pitched down two or three octaves. And then you are pretty much there – you can tweak it a little bit with some enhancer, or like Stephan said with an EQ, but the basic sub sounds you get from the real recordings.

Stephan: It’s the trained voices. One thing that blew us away was the sound of the bass singers in Bratislava because they are professional choir singers and if you say, “okay now everyone sing an ‘ah’ vowel on the lowest note possible”, you would expect them to go like (sings low note) but they go so much lower. It’s a real experience.

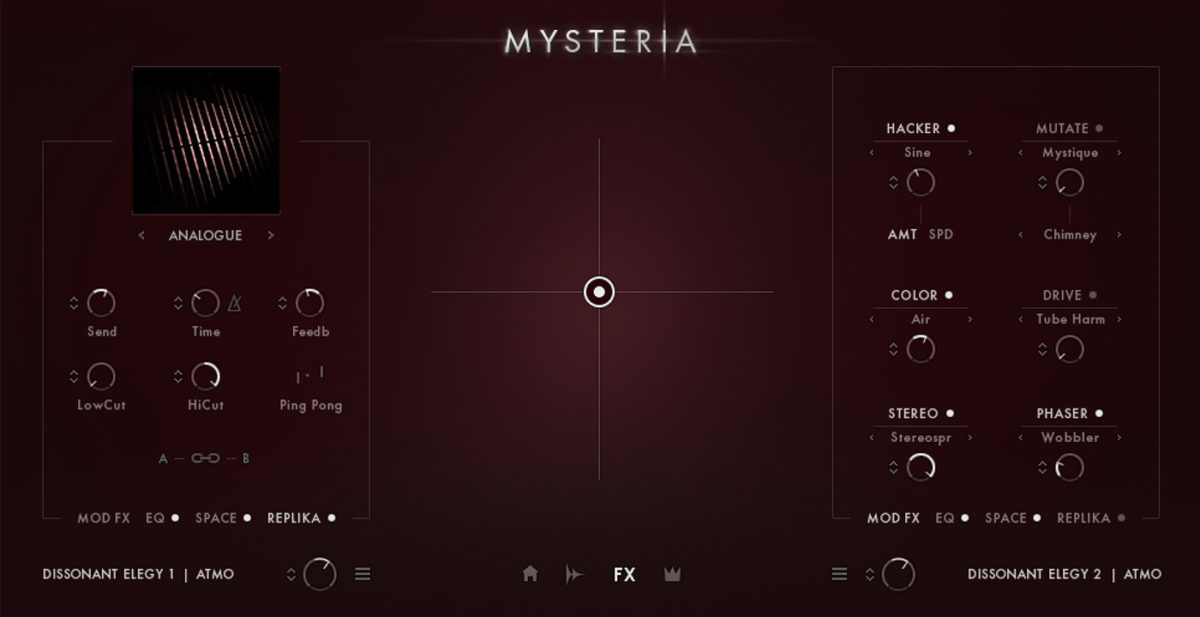

One last question, about effects. There are loads of effects available to customize in Mysteria, and one of them is just called “The Hacker”. In the manual, it’s described as “an LFO-based effect that add motions to sound,” but it feels like it’s doing something a little bit more than a basic tremolo.

Stephan: Mostly it is, but it has lots of curves. The basis is a step sequencer, because if you want to do something like this you have to use a step sequencer in Kontakt, and then create something from there. And so you carefully have to design those curves to do something. For example, if it says it’s a sine wave it’s of course not a sine wave; it’s a 128-step approximation of a sine wave. And so we thought “Okay, what else can we do”, like the Dirac impulse for example, so we get some really tight waveforms.

Uli: The main point for me where the Hacker works nicely within this instrument are the textures, because the textures are continuously evolving or developing all the time. And if you then put some kind of simple Hacker on it, then every little bit you hear is different. It’s like a modulating filter on it all the time; you simply don’t need to do that because the basic material, the source material, is continuously developing. So if you hack it every little bit is different. I think that’s the main point where the Hacker works nicely.

Get all the details and hear more sounds from MYSTERIA, then don’t forget to check out Galaxy Instruments’ other recent creations for Native Instruments, THRILL and NOIRE.