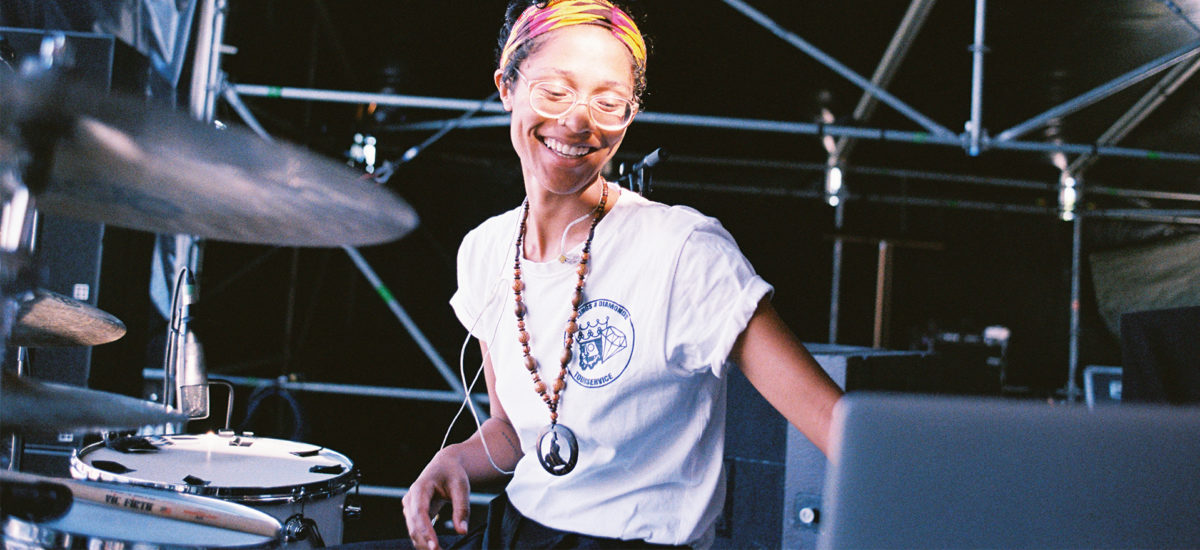

Originally a student of classical percussion at the Musikhochschule in Munich, Philo Tsoungui sparked an interest in hip hop drumming after meeting Mark Colenburg, the drummer for jazz musician Robert Glasper, in 2013. Three years later, the German artist transferred to the Mannheim Pop Academy, where she quickly made a name for herself outside of classical music by bringing next level musical concepts to various live rap shows.

Earlier this year, we caught up with Philo after she provided 32 drum one-shots and four drum loops to our COVID-19 charity sound pack, COMMUNITY DRIVE. (On top of that, her acoustic and electronic drum kits for BATTERY, MASCHINE, Ableton and Logic are available for free download.)

Speaking via video call from her apartment near Bremen, Philo sat among her drum set up. Over the past few months, with touring on pause, the artist has immersed herself in producing, beatmaking, and working on her own sample and loop packs. Given the stay at home orders of the current global crisis, Philo, for her neighbors’ sake, has been perfecting one thing above all: Playing drums quietly.

Can you still enjoy playing drums quietly in your apartment?

It’s definitely a challenge, but also fun. I definitely feel the urge to play loudly again, though. Playing quietly results in completely different things compared to just playing like I’m used to. I can’t compensate or cover up anything with volume.

How would you describe your job?

It’s a blend of musical direction and drumming. Both include similar tasks, but on different levels. When I do musical direction, it means I have to convert studio productions into a live show. For me as a drummer it means I have to transfer the production into the live situation using only the equipment I have at hand.

What enables someone to make the step from playing drums to musical direction?

First and foremost, an organizational talent and a dry, almost bureaucratic way of dealing with things. I have been working in various genres, played a lot, studied a lot and come from the classical music scene. It works via hierarchy and clear structures, and I have intensively observed what is good and bad about it. It is also important to have a well-trained ear and to be able to think your way into the visions of an artist like a chameleon.

Speaking of workflow, how do you start?

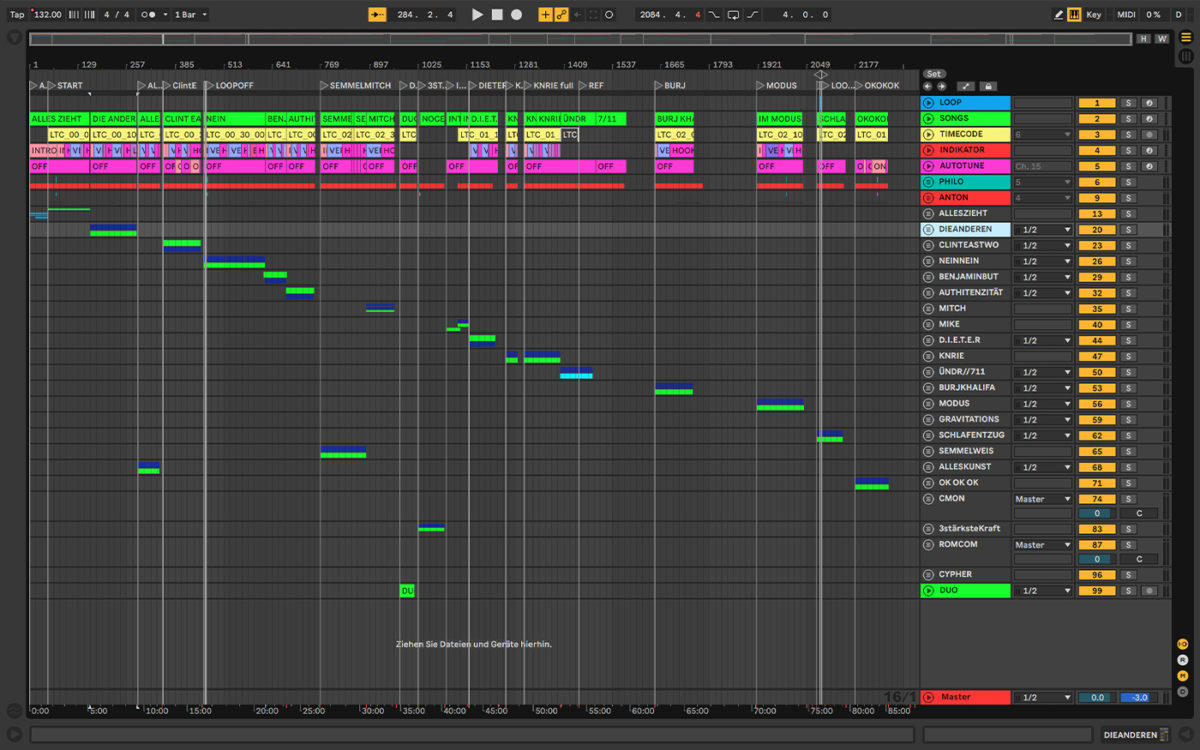

The first step is to get all stems that exist, all instrumentals of songs that come into question. I create a set where I put in all the stems. That’s huge, of course. In this jumble of unravelled songs, I try to find a common thread, a way to connect everything sound-wise without completely rearranging it. From a drummer’s point of view, this means: I have an 808 kick, an 808 snare and an 808 hi-hat. What do I make of it without losing the character of the sound? What will be replaced, what do I let run along, where do I play acoustic drums over it? It’s also about levelling so that everything is already mixed properly and the sound engineer is not stressing out too much. Finally, it’s about the dramaturgical arc of a show, which means a lot of puzzling and pushing back and forth. All this happens in this first set in the DAW. From this, I end up mixing my tracks so that a maximum of eight channels go out. These tracks go into a new set, that is only for live and eats up as little CPU as possible.

How much do you deviate from the original version of a song?

At the beginning of the song, I like to stay close to the studio version. The audience usually likes that and you have one foot in the door right away. When adding drums, it always seems louder and more energetic. I love transcribing the programmed patterns for myself so I can play the grooves exactly the same way, even if they have multiple layers. I usually sacrifice that one snare, which comes in every 25 bars on the last sixteenth of the second count in favor of the live experience, so I don’t have to concentrate on it anymore. Something like that goes into the backing track or I leave it out completely because it gets lost anyway.

What’s important to you in a setlist?

I’m a fan of intros, outros, interludes, and things that generally keep a concert cohesive. We don’t just go on stage, press play, and listen to an exact reenactment of a record. I have higher standards than that.

You’re working with a lot of self-taught musicians while bringing a huge package of formal musical training to the table. How do you find a shared musical vocabulary?

It’s an interesting journey. You’re dealing with many uncertainties. Sometimes I assume too much that people understand me, meanwhile the other people assume that they can’t make themselves understood or aren’t taken seriously. So I try to ask a lot of questions. You should communicate openly and at eye level. We have the same goal.

Sometimes it’s just two of you on stage: you and the artist you’re supporting. In other scenarios it’s four or more people. How do you handle these differences?

When five of you interact on stage, you have the feeling that the responsibility is also divided by five. When I’m alone, I have to be extremely focussed and always give 100%. In addition, you have to pay attention to the laptop and the interface. It’s a challenge to create a 90-minute show all by yourself.

What does your setup look like on stage?

At the core is a laptop plus DAW and interface. Not much happens in the DAW—tracks that I mixed beforehand are separated into high, mid and low frequencies. Different click tracks and timecodes for the light show are also running on it. I also have a second laptop with me, that can be used if the first one drops out. I control everything via MIDI—on the one hand with my Roland SPD-SX, and on the other with a keyboard or a MASCHINE as MIDI controller. I get along well with the big MASCHINE pads. I press start and stop, fire off a sample or jump around in the Session View of Live. When I’m playing drums and need to press stop quickly, I prefer to hit the SPD-SX with a drum stick rather than hitting a controller with my finger. When playing songs without drums, I usually slice the samples and play them on the MASCHINE pads.

Let’s talk about producing. How do you use MASCHINE?

I use MASCHINE mainly to flip and process samples. Mostly, I record loops in Ableton Live and mix them there. I put that into MASCHINE and see what happens. I try to use the drums I’ve recorded and slice them in MASCHINE to play different patterns and understand them in a different way. I also use MASCHINE as an inspiration to find harmonies, because as a drummer, I don’t sit down at the piano and immediately have the idea which chords and progressions are fitting. Mainly it’s about drums and, in the long run, about establishing my sound so it’s clear: This is a Philo loop. MASCHINE helps me understand how drum patterns can be thought of in a different way in order to get as much color, layers and diversity into a loop.

How do you convert your drum playing, two arms and two legs onto a controller?

Playing drums is a very graphical thing. Everything is arranged in triangles or squares: the toms, the cymbals… When I hear a groove, I immediately know what it looks like when you play it. I transfer that to the machine. I try to see a kind of drum set on these 16 pads when I arrange samples. The cymbals are on top, the hi-hat is underneath, then the snares, the kick drums at the bottom.

Are the samples you’re playing always your own?

It always depends on where I am and if I have the possibility to record something. Sometimes I build a groove in MASCHINE, try to record it and then use it again. This is a tough challenge because I can do anything I want on the computer, things I can’t do with only two arms and two legs.

Do you create things on the screen that you usually wouldn’t play?

Yeah, sure. I imagine the groove first—hi-hat, kick, and snare. But then I hear something else, some layer that interferes, that buzzes over it in a polyrhythmic way or something. That’s when I get ambitious because if my brain was able to come up with that, it must be playable. Maybe I have to think of the groove in a different way to get as close as possible to the version from the DAW. That’s how I bounce ideas back and forth between me and MASCHINE.

What effect does that have on you as a drummer?

It opens a new door and shapes my self-image as a kind of living drum computer. Every decision to change a groove has to be very conscious and your hearing needs time to adjust. Especially with monotonous things. Whether a human being or a DAW is playing, there’s an appreciation for small changes, even if you’re not aware of them on a conscious level. This made my drumming a lot more informed. I don’t have to offer something new every four bars to be perceived as virtuosic and competent. People like Questlove or Chris Dave have this gift of playing a groove with consistent dynamics, a simple set of hi-hat, snare and kick. And when hitting a tom, it makes all the difference at that moment.