David Willis, better known as Ski Beatz, came up as a music producer in the mid-90s. He produced seminal work along multiple branches of hip hop’s golden era giving tree, including debut albums from both Camp Lo (Uptown Saturday Night) and Jay-Z (Reasonable Doubt). Over the years, he went on to work with the likes of Mos Def, Jay Electronica, Jean Grae, Curren$y, and Ras Kass, among many others.

More recently, and very much by choice, Willis has found himself increasingly alone in the studio. His latest album, Switched On Bap, is something of an ode to Wendy Carlos’ seminal Switched-On Bach — it’s an exercise in hip hop production that puts Willis’ newfound love of modular synthesis at the forefront. Native Instruments spoke to Willis about his own relationship with sampling, and the continuing evolution of the form.

You’ve been making music for several decades now. How has your process changed, and how do you keep things fresh for yourself?

Well, I started as a sample-based producer. So my original process was going through crates, looking for nice tidbits to chop up and manipulate, finding some good grooves and dope drums, constructing records from some samples — hence the Jay-Z records and the Camp Lo records, and all the music I did before. But nowadays I’ve been doing everything with my modular. I’ve been coming up with dope grooves and things myself, that I can then sample. So I’m still sampling, but I’m just sampling my modular right now.

It seems like that’s kind of rare in hip hop. How did you stumble into the modular world?

Well, I’ve been sampling records since way back…like 1986, wow [laughs]. And I don’t have anything against sample-based producers at all, but for me it kinda ran its course. It went from a labor of love to just being, like, labor…ya feel me? So I needed something that was going to kind of expand my creativity, and I wanted to get out the box. I got tired of the same approach.

I hear a lot of people talking about today’s music, like trap, saying, “All the trap music sounds the same, the producers all do the same thing.” But when I listen to sample-based producers, they’re mostly somewhat similar to me too; when I hear sample-based beats, they all have that similar kind of feel.

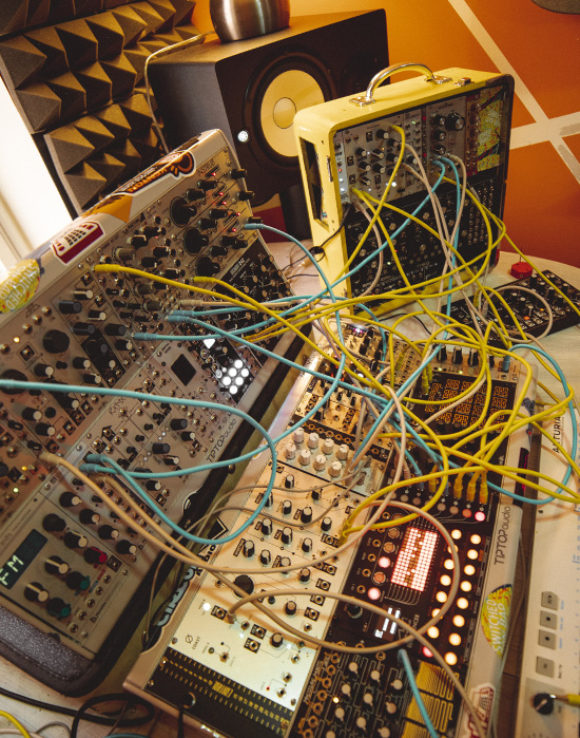

So I just wanted to step out the box. I got me a little Mother-32, just to kind of introduce myself to patching with a semi-modular, and once I got pretty good at that I just started building a rack and a whole synthesizer. And now I’m in the rabbit hole — there’s no turning back, man [laughs].

How did you go about choosing your modules? Did you have a specific, long-term plan, or were you just sort of experimenting?

Well, I’ve got some percussion racks and crazy FM-type things to give me different textures, but mostly my rack is a melodic machine right now. It’s a melodic beast.

While I was learning how to operate these modules, I was coming up with crazy sounds, and started putting beats and songs together that I was creating while I was learning. So it was a cool process, and I ended up having like 10 tracks that I thought were pretty cool put on an album.

Putting together the album kind threw me into the whole modular world super deep, I had to really figure things out. And this is a rabbit hole, I’m still figuring stuff out — it’s like, unlimited possibilities. There are so many other modules that I want to get, just because of the little bit of knowledge that I have right now; it’s like every day I’m learning some new patching technique or some way to get new timbres. It’s super interesting. I love it. I might start with an initial idea, but the modular will always take your idea and do something totally different, to unexpected outcomes.

So you’re essentially building patches on the modular, and sampling that raw material into the computer? What does your workflow look like?

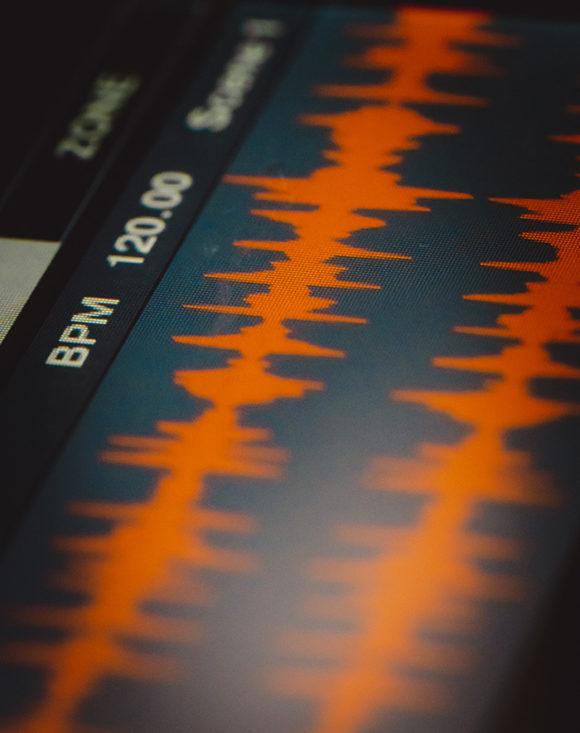

The modular is doing a lot of the musical work, but the MASCHINE and the other things that I use — I still need that for its structure, and to put things together. It’s perfect for that; it’s the brain of the operation, while the modular is the music machine. Musically, [the modular] gives me a whole different approach, and when I throw that into the Maschine or whatever else I’m using, it meshes perfectly. I try not to even look at the computer — just go right from the modular to the MASCHINE.

Switched On Bap is just the drum machine and the modular; obviously, I had to dump it into the computer to track it out and get it mixed, but for the creative process it was strictly analog. It’s crazy — I was documenting some of my process on Instagram, and Young Guru reached out to me and said he loved what I was doing, to the point that he mixed the whole album for me, for free.

In hip hop, are you finding that it’s becoming more common to see producers experimenting with modular gear, or do you feel like you’re still an outlier in that world?

There’s a few guys that I know that get into that in the whole modular hip hop thing, but it’s definitely super new and nobody’s really doing it. The learning curve is crazy, you need to know about cases and power supplies and so much stuff, and that almost put me off it, to be honest. But I stuck with it and I figured it out.

But yeah, the learning curve is crazy, so I think it’s gonna be a minute before the majority of hip hop producers kind of embrace the concept. People love their software, love their plug-ins and presets — and there’s nothing wrong with that, but obviously modular’s like a whole other universe, just untapped, endless resources of good stuff.

It’s amazing how it forces you to sort of slow down and pay attention to certain finer details.

And the thing is that you don’t mind the process because it’s so much fun. It’s like you’re becoming intimate with your machine. I’m a 90s producer, so we didn’t have software back then; we had to really become one with our equipment, just constantly tweaking and turning knobs, and getting intimate with a piece of equipment — I missed that feeling, and the modular brought it back, and made me realize how I just love production so much. I mean clicking a mouse is cool, but sometimes I don’t want to click a mouse, I want to turn some knobs, hit some keys, and actually interact with this shit.

How did you first hear about Wendy Carlos?

Me just record collecting. Every time I’d go you know these thrift stores or these Goodwill places, there would always be a Switched-On Bach album there. And I always thought it sounded cool, and when I was trying to come up with a name for the album it just clicked.

Your career spans back through the hardware generation, into the software-based production era, and now back to using primarily hardware. Have you been experimenting with new forms of sampling with eurorack?

I got the Make Noise Morphagene, and it’s incredible. It’s more of an old school tape machine mixed with a granular synthesizer, and it just mangles your samples, man. It definitely takes you out the box of traditional chopping and looping — it’s some other shit.

Many of the samples on Switched On Bap refer to production techniques over the years, and the constant, driving need for new energy. What are your thoughts about modern popular music?

Trap is disco right now. Remember how disco was? They had to shut it down because they kept doing the same beat. Creativity is gonna have to come back into the circle for people to get inspired again. Don’t get me wrong, you’ve got guys that are making it and it sounds really good, but then you’ve got 200,000 other guys that are just copying these guys — you can tell the quality ain’t the same, and it’s the same message, the same story, the same concept, the same energy. It’s like yo, I don’t want to be turnt up all the time. There’s a time and a place for that. Can we just vibe out for a minute? Can we just listen to some music that kinda pulls at our heart strings or takes us emotionally somewhere else for a minute, and then maybe later in the club we can get turned up? Maybe?

I feel like it’s definitely time for the tables to turn. This is the perfect environment for someone to come and drop something creative. We need different food on the menu. I’m tired of ordering that same old burger — I need something different.

What inspires you these days? What are you listening to?

Man, I don’t listen to really anything [laughs]. I just kind of try to create what’s inside of me. I’mma just keep it 100 — I don’t get inspired by any music that’s out right now. If anything, listening to 1970’s electronic music like Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream, just to give me a whole different energy. But I’m definitely not listening to any hip hop or anything like that. I’m just trying to come 100% from the heart.

I get inspired by all types of different things — movies, video games, everyday life kinda stuff. And I’m all about the timbre man, I don’t wanna hear a basic sine wave, square wave, saw wave — I want to sound like some other shit, you know? So I’ve been doing a lot of studying on how to get these different timbres, and how to get these sounds that nobody else got.

Photo credits: www.dropkickjoshphoto.com