Timeless sound in music production is a concept that often defies easy explanation but is that ephemeral gold standard that all music producers seem to chase. For St. Lucia, it’s about blending the foundational elements of past eras with subtle modern touches, crafting something that feels familiar yet distinct.

Their latest album, Fata Morgana: Dawn, expands on this approach, drawing inspiration from 1960s and 1970s psychedelic pop, the pre-1980s NYC dance scene, and classic film scores. Mixed by Chris Zane (Jack Antonoff, Passion Pit, The Walkmen), the record balances organic band performances with orchestral elements, pushing their sound further than ever.

In this interview, St. Lucia shares how tools like Native Instruments’ Kontakt help achieve these timeless qualities, offering insights into recreating vintage tones, building unique sonic palettes, and embracing the imperfections that make music relatable.

They also discuss the process behind Fata Morgana: Dawn – a project that started with a lo-fi 1970s aesthetic but evolved into their most ambitious work yet, incorporating live strings and cinematic textures to elevate their sound.

Jump to these sections:

- Defining what “timeless” sounds like

- Tools vs. how they’re used

- St. Lucia’s go-to sounds

- Resampling techniques

- Making classic sounds unique

- Essential advice for producers

From utilizing classic keyboard libraries to manipulating Kontakt samples for added texture, this conversation dives into the practical techniques and philosophies that shape St. Lucia’s distinctive sound.

What does “timeless sound” mean to you, and how has Kontakt helped you achieve that in your music?

Timeless sound is honestly hard to define. The way that I imagine timeless sound is something that draws from the past but also adds a bit of the present. I’m very interested in architecture, and there’s this amazing book called The Timeless Way of Building that goes about attempting to define what timeless architecture truly is.

There’s obviously more to it than what I can write here, but essentially a timeless building is one that is very rooted in the place that it stands, draws on the architectural traditions of the other houses in the region around it, uses as many natural materials as possible, has very few right angles and considers the experience of the people who are going to be living in the house and where the light comes from etc.

The way that I apply this idea to music for myself is that I mostly try to use a sound palette that is rooted in ‘classic’ sounds from the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s because I love the sound of those records, and most of my favorite records from the modern era also use those sounds.

There’s thing thing called the Lindy Effect, the gist of it is that you can bet with pretty good odds that things that have been around for a certain amount of time will be around for at least that same amount of time into the future, because things stand the test of time for a reason.

So I try to use that classic sound palette from decades I mentioned above (also the 90s actually, but the 1990s started the feel to me more like they were referencing the past) because it’s stood the test of time, drums, bass (or bass synth), some kind of keyboard part (Wurly, Piano, Rhodes, CP70), a polyphonic synth part, a rhythm guitar part, acoustic guitar, vocals, a synth string part, real strings… I could go on. I roughly use the 80/20 rule in that I try to have around 20% of the track have something weird or unexpected or messed up or something.

The other part of this is not trying to overly perfect things. The houses or buildings I love the most are the ones that are made out of Adobe or other natural materials and don’t have walls with perfectly flat surfaces, have a lot of wood and are generally made of natural materials and maybe have vaulted ceilings etc. The reason for this, I’m convinced, is because we relate to these buildings more because we are imperfect.

It’s better for us to be surrounded by things that are imperfect and have a natural patina rather than gossip magazines full of airbrushed models none of whom look like that in real life but nonetheless make us feel worse about ourselves.

Similarly with music, if everything is too perfectly in time and in tune, it feels cold and distant, and it’s harder for us to relate or connect.

Do you think recreating vintage tones with Kontakt is more about the samples you choose or how you use them?

I think it has a lot to do with understanding how signal flow and processing works. In my view, I always try and start with the highest quality and best version of a sound, and Kontakt has many examples of great ‘vintage tone.’ It’s like when you record, the most important thing is the source itself (the instrument) and how it’s played, and the next most important thing is the microphone, the preamp, the converters or tape machine and so on.

So I definitely think the first most important thing is the source itself, the sample library you’re choosing, and that it feels tactile and immediate for you to play. What’s great about using samples in Kontakt is all of the high quality recording parts are taken care of for you, and so your job is more just to make the sound your own.

A big thing I’ve realized over the years when using samples (especially if everything in your track is samples or soft synths) is that you have to be mindful of how a sound fits into a track. Most vintage style sample libraries are extremely well recorded, and that’s great, but that can also work against you. If you listen to a lot of older recordings, many things were mono, or even most things, and often drum kits were only recorded with one mic.

I’ve also worked with Homer Steinweiss from the Dap Kings and he explained to me that his main drum sound is literally just one ribbon microphone placed at a place in front of the drum kit where the balance is right.

The problem with using only sample libraries is that if all the sounds are well recorded and stereo and wide and full spectrum, which sounds great on its own, it can be too much when you put it all together. So, to me this is the challenge of working with samples, and it’s also why the flexibility of the sample libraries in Kontakt is so awesome. Most of the time with sample libraries what you need to be doing is trying to make the sounds smaller, not bigger.

What are some go-to Kontakt libraries you use to instantly tap into that classic, timeless vibe?

The Kontakt Factory Library: This is where I started with Kontakt almost 20 years ago and I keep going back. There’s so many great sounds in there, and I still use the tubular bells and timpani in the VSL Symphonic Percussion section all the time. Also, most people actually shy away from using factory libraries because there’s a perception that it’s somehow cheap to use or everyone is using it. But it’s exactly because of this perception that it can be a secret weapon in your arsenal.

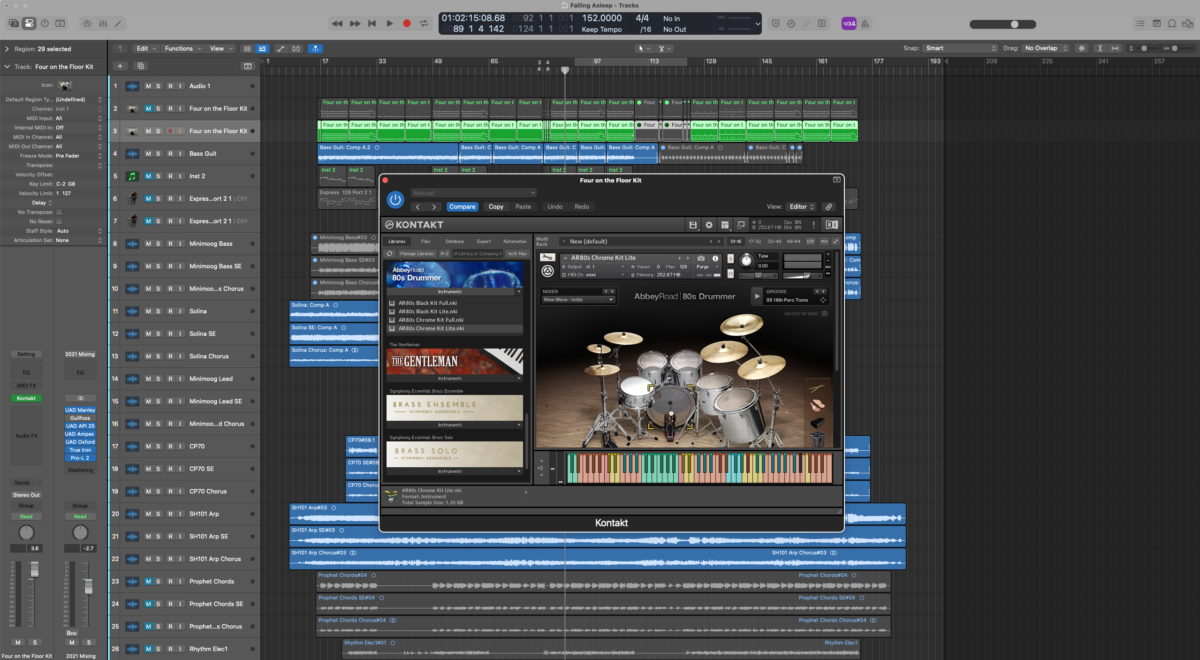

All the Abbey Road Drummer libraries, especially the 1970s and 1980s kits: I really love the flexibility and sound quality of the drummer libraries. Most of the time I start by using one of the drummer libraries when in the demo phase, most often one of the 80’s kits, and then at some point I replace the programmed drums with our drummer Dustin playing drums. But there have been a bunch of occasions where when I recorded live drums, I still missed something from the sound of the programmed drums.

For example, one of our biggest songs ‘Elevate’ is kinda famous for its big 1980s style Phil Collin-esque tom fills. That sound is a combination of real toms and timbales and rototoms from the Abbey Road 80s drummer kit. There was something about that sound that we just couldn’t top with our own recording.

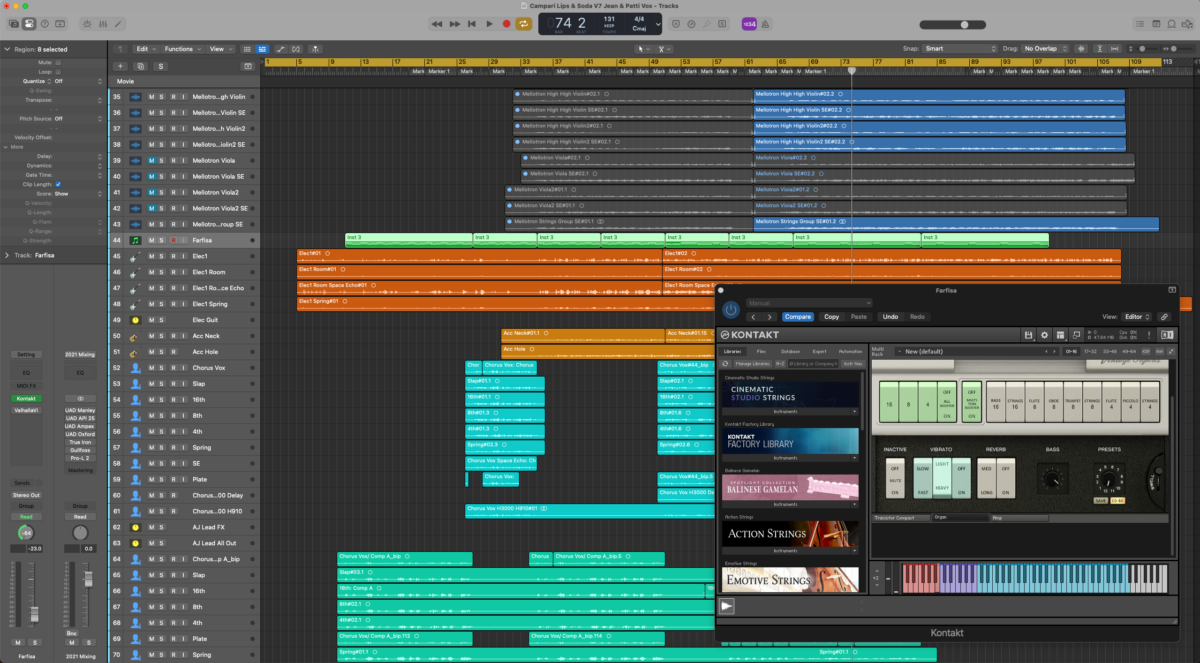

Vintage Organs: Without a doubt my favorite emulation/sample library of a transistor Vox/Farfisa organ. I use this sound often as part of my sound palette, mostly the ‘Cornichons’ preset. I really love the sound of the built-in spring reverb too. I’ve even gone about trying to replace this sound with a real Farfisa or Vox organ before and stuck with the Kontakt library.

I’ll often go to reamp the sound through one of my guitar amps, which I do with almost everything, but I could also just be happy with the sound as it comes and have used it like that many times.

What are some of your favorite processing and resampling techniques?

I have a few amps and outboard effects in my studio that I love running things through.

Often the goal isn’t even to make things sound ‘better’, the sounds are already so good. It’s more to give them more of a unique sound of my own and almost make them slightly smaller and bring them into my world more.

I honestly barely use any effects plugins in my sessions because I’ve learned that I get more unique sounds by using what I have in my studio. You could obviously do the same thing with plugins, but I like limiting myself as much as possible to what I have that’s around me. I feel like people are drowning in options these days, and it’s kinda a luxury to be limited. So almost every instrument I record I either mult the sound out (meaning send it to and record back in) while I’m recording to my Stereo Space Echo RE201 setup and Dimension D.

I then just have those tracks as the effects already in my session and I can blend them as I see fit. I’m very conscious of phase and so I always make sure that the Dimension D or whatever I record back in is phase aligned using a plugin called Auto Align that is very useful, it might seem like a small thing but you’d be surprised at home much of a difference it makes, especially over the course of a whole session.

So after that initial recording, depending on the sound, I’ll try reamping the sound through one of my amps (I have a Vox AC30, a Fender Twin Reverb and a vintage Ampeg SB-12 that live in my studio) which then goes to an ISO cab called a Rivera Silent Sister (which I found out about from RAC) and I have two mics that live in there. Of course in the reamping it’s also very important to use a reamp box so that the impedance etc is correct for an instrument level input on an amp.

For anyone that’s reading this that wants to try this, just starting with reamping things to whatever guitar effects pedals you have lying around is a great experiment. There’s just something about taking things out of the computer and putting it into the ‘real world’ that changes things for the better in some way.

Even if you don’t have any outboard gear other than your interface, speakers, computer and maybe a microphone, you can try just playing a sound through your speaker and put the mic in a weird place in your room and record that sound. It might sound like utter trash but that might be just the thing that makes the track interesting.

Or put a speaker in your bathroom and record the sound there. On Fleetwood Mac’s “Tusk” many of the Lindsey Buckingham tracks were made by him in his house and a lot of the reverbs are just his bathroom. You might have all sorts of amazing acoustic spaces all around you. I record most of my percussion in this amazing stairwell we have in our house that just sounds incredible, and I’ve even put speakers in and recorded the sounds back in.

None of this is because the original sounds themselves don’t sound good. Most if not all of these sample libraries are incredibly well-recorded and tactile. This is all more about taking that initial sound and making it your own, creating something unique. Showing people your point of view.

When it comes to classic keyboard sounds, like the Wurlitzer or Rhodes, how do you make them stand out in modern production?

I’d say my production ethos actually isn’t very ‘modern’ in the way that I think of the word. To me the idea of ‘modern’ production feels like something that is disconnected from the past, and I actually feel the past has a lot to offer. One of my favorite writers, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, whose book I found out about the Lindy Effect from talks about how if you really wanted to write an accurate science fiction book you should get rid of more things than you add.

Most things just don’t stand the test of time, like for example a microwave.

When they first came out everyone thought that this is now the way we’re all going to eat forever. Whereas now most people I know don’t ever use their microwave other than maybe reheating meals, if that. We all long for the ancient ways of cooking over fire.

So I don’t really change the sounds much, other than what I said above. I try to keep the sounds as natural as possible, maybe with a few small additions. I trust that this is a great sound and we don’t need to reinvent the wheel every time we do something.

Actually most of the time you shouldn’t have to reinvent the wheel. Experimenting a bit is cool and you never know where that might lead you, but any time I’ve gone and really deeply messed with every single sound in a production it can get hard to make things sound solid, especially when it comes to bass sources.

All this being said, I do think it’s great to mess with things, and you have to follow your gut here. But I think if every single instrument or sound in your session has 10 plugins on it you’re probably going to have a hard time, although I might be wrong. Less is more when it comes to processing, but having a few totally messed up things is good.

What advice would you give to a producer trying to use Kontakt to recreate iconic sounds from their favorite records?

Go and do some reading and research into how people did things on those records.

How were things recorded, what was the philosophy and ethos.

Trying to understand recording instruments in the real world is very helpful too, even if you never use any of those recorded tracks and you only use samples or soft synths. The way sounds fit together on records doesn’t come from everything being recorded as hi-fi as possible, it comes from someone using their ears and having a know-how about different effects and how they work and mic positions etc and using that to craft something unique. If you have even a slight understanding of that, it will help you navigate effects in the box.

Even when it comes to music that is completely electronic, using real world ambience and distortion and effects can give a track an edge. A dear friend of ours Neil McLellan who co-produced and mixed most of The Prodigy’s records told me that they used one of the rooms at Strongroom Studios in the UK as a reverb.

So even though there were all these electronic sounds, he was sending them into the live room and reamping it in there and they mic’d up the room and recorded it back. Some of my earliest recording experiments involved sending things out in the room that I worked at at the music house I worked at for a while when I first moved to the US. I messed up a lot of things but I had fun and learned a lot.

Just be an explorer. Ignore what I or anyone else tells you, or listen to it but don’t take it as gospel. People have found ways to do things and make great records that span every possibility you can think of. Lo-fi, hi-fi, super clean, messed up. It’s all good. You have to find your way, I’m still finding mine. Just don’t always take the easy road. Travel down some dark wooded paths. Try something everyone tells you not to do, and even if they’re right in the end you can own your mistakes.

Create timeless sounds in your music

Timeless music is about balance – taking the sounds you love, respecting their roots, and pushing them somewhere fresh. St. Lucia’s insights into using Kontakt to recreate iconic tones and his philosophy of blending imperfections with intention really hit home.

Whether it’s reamping sounds for character or embracing a minimal, natural workflow, the takeaways here remind me how much authenticity comes from not overthinking.

At the end of the day, it’s about letting your personality show through the tools you use. Hopefully, these tips inspire you to dive into your own creative process with a little less perfectionism and a little more freedom.

That’s where the magic happens.