“They gave us a world that is fucked up!” exclaims Simone Trabucchi over the line from his Milan studio. “Somehow we have to fix it, I think.” Recent music from Trabucchi, a veteran of the Italian experimental scene and the head of Hundebiss records, has been true to this sentiment. It all started with a multidisciplinary art project from his duo Invernomuto. Encompassing sculptures, installations, a book and a feature-length film, ‘Negus’ used a historical incident in Trabbuchi’s rural hometown to explore Italy’s colonial occupation of Ethiopia and Eritrea, and the cultural threads binding Europe, Africa and Jamaica.

Whilst working on the project, Trabucchi made some music inspired by its ideas: sidewinding riffs on Jamaican dancehall riddims, which would eventually be complemented by the voices of six African-Italian MCs and singers. The result was the debut album of a new project, STILL. Wild, fun and futuristic, and a thoughtful examination of the global cultural flows which shape electronic music, I (released on PAN) has been one of the standout albums of recent years. As Trabucchi puts the finishing touches to its follow-up, he spoke to Native Instruments about the thinking behind the project and the role that REAKTOR played in his studio.

Let’s to go back to the start of STILL. What made you want to do something around dancehall?

We have to start from Jamaican Music. Jamaican Music is the foundation of electronic music we are hearing now. I really think a lot of electronic music was invented there. With the studio techniques they developed in dub, and with dancehall also. Dancehall was such a revolution because it was a cut with tradition. It’s a very postmodern music, I think. For a tradition like Jamaican music to completely cut with drumming, with live drumming, and go all the way digital. It’s a break in history that—there is not much to compare it to in the rest of the world. And the impact that had on the rest of music is huge. It was such a break with tradition that there’s space to take it and make my own experiment about it. I don’t feel comfortable, for example, sampling traditional music, from whatever place. Even if it’s like a Finnish chant, you know. But I think with the approach [I took] there was space to get inside it, to make my own version of it.

Dancehall is also music made for the purpose of making you dance. They had standards, they had dogmas. You can go crazy but you have to stay inside a certain grid. The first thing I did as STILL was a mixtape of riddims I’d collected. I’d never made rhythmic music, so I started doing some experiments, after a big analysis of these riddims. And then I found my own way. I really think it’s far away from dancehall. People who actually listen to dancehall are like, ‘what the fuck is this?’ Which is great for me. I’m not interested in stepping inside that scene, in taking a space that is not mine. I believe you can be grateful as a producer, but it’s important to create my own space.

The idea of cultural appropriation, and when it’s OK to borrow from another style, is often discussed these days. Were you thinking about this when making the album?

When I started the ‘Negus’ project I was very aware of that. It also took me years to start because of that. I had to find my position. The beginning point was actually a personal experience, something that happened in my village. When you do a documentary, you have to talk with people, and this is a good starting point. When they asked, ‘Why are you here, what do you want to know?’, I said, ‘In my village, during the Italian occupation of Ethiopia, they burned a puppet of Haile Selassie. Can you explain to me who is Haile Selassie for you?’ Without that I would have been too out-of-the conversation, too much of a spectator. But now there is a conversation. And a re-signification. Re-signifying stuff is what our generation has to do. No matter where you come from, it’s a real important task. They gave us a world that is fucked up! Somehow we have to fix it, I think. The other important thing was having vocalists. To have a dialogue.

How did you connect with the vocalists on the first album? Tell me about the Rainbow Café.

Rainbow Café is a bar in the so-called African block of Milan, Porta Venezia. Since the ‘60s, that area was the Eritrean and Ethiopian area, [where] there’s always been a community. Rainbow Café opened there a few years ago. I think it’s the only bar that worked a bit out of the community also—it’s not only for the Eritrean or Ethiopian community. And younger people go there. It’s a very chill meeting point. The owner and bartender is Elinor, who is the singer on “BANZINA”. I started talking to her because I wanted to do a spoken word in Tigrinya. She translated and read it for me. Then she started saying, ‘You have to meet this lady who sings’—which was Freweini—and so on. Except for Devon [Miles], all the other singers came from there. It was a hub. Tomorrow I’m going there to meet with Fre’ and have a drink. So I still feel it’s a headquarter, somehow.

What are you working on at the moment?

The new album, actually. Next week I’m going to Berlin to mix it. I went to Uganda for two months this summer, invited by the Nyege Nyege guys. They invited me to work with local MCs. The first days it was very crazy because a lot of [MCs] showed up, much more than expected. At the end I decided to work with four to six MCs. Not that I selected, like an audition—it was natural selection. It’s weird music, it’s not like traditional dancehall or hip hop, so not every MC can ride it. And it went great, I’m very happy.

How did it compare to the process of making the last album?

When I did the first record I did the riddims, then I found the singers, then we recorded. [With this album] I think there is more space for the vocals, because I was mostly playing the [vocalists] a draft, then I arranged the song around the vocals. It’s more organic somehow, and definitely a bit more like a conversation. Which for my way of working is very stimulating.

Is there a conceptual framework for the album, as with the last one?

This album is less conceptual somehow. The first album was the creation of STILL as a platform, as a spaceship [laughs]. The second album is like, we’re riding, we’re going. Everything is there already. Even in the music production you feel it, everything’s a bit more smooth somehow. I did stuff in a more immediate way, more simple. Also because you can’t bring much when you’re travelling. My drum machine, my computer, that’s it. All the synthesizers were virtual synthesizers. The album before came from a session I did in Vancouver with analogue synthesizers. And there’s a big difference.

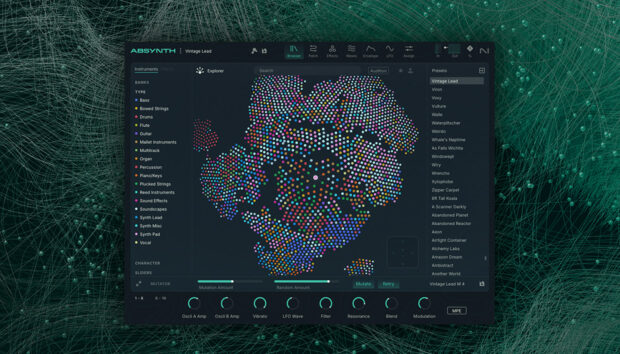

You also used REAKTOR BLOCKS WIRED on the previous album, right?

Yeah, I like it a lot. Because it’s free—it sounds stupid to say, but it’s important that you can have software like that for free. And because it’s unpredictable. I love when synthesizers are unpredictable. I want them to surprise me. With analog synthesizers it happens quite often. With digital, it never happened to me, but with BLOCKS WIRED it happened and it was surprising. I was actually using it in a track I was making yesterday night. One thing I was noticing is it’s so loud – it’s strange, almost. Sometimes it’s a problem: it’s too full, it’s covering the other stuff. I have to go to the EQ and cut some frequencies. You could make a record only with that, it’s really powerful.

What kind of sounds do you use it for?

On the first album I had an obsession with kind of percussive high tones. The EMS Synthi is a good example: a high frequency, rounded, percussive sound. Very precise. [With REAKTOR BLOCKS] you can find interesting sounds that can make a dialogue with that sound. They match. I like that a lot.

After using the Synthi in Vancouver on the first album, did you think about getting a hardware modular synthesiser yourself?

No. I understand why they’re popular. They’re fun and they’re good if you know how to use them. At the same time I don’t have time to waste on that. And to me [BLOCKS] is a very good alternative. The sound is very similar, I would say, for what I’m doing. I think it does the job.

photo credits: Guido Borso