Few dance scenes have a history quite like New York’s. From 1920s speakeasy bars, to legendary temples of house and hedonism like Paradise Garage, Limelight, and The Palladium, the residue of jacking bodies, subcultural subversion, and all-night adventures is soaked into the fabric of the city. New York’s nightlife has always been iconic – as much a part of the city as the distinctive yellow cabs that ferried club kids from spot to spot, or the silver subway trains that would shuttle them back to their apartment blocks when it was finally time to go home.

New York’s nocturnal heritage outstrips that of almost any other city – although it has fought hard, and against the odds, to keep it. 1994 saw the beginning of Rudy Giuliani’s mayorship, which oversaw the resurrection of prohibition-era cabaret laws that banned dancing in clubs, and threatened to financially cripple establishments that broke the rules. 2017 saw the law repealed, and while it might not mean much in practice, it’s a kind of barometer for the health of the city’s nightlife, which has seen a boom in recent years.

Eli Escobar, who over the last two decades has grown to be a heavyweight of the scene (and more recently across the world), cut his teeth during the last few glory days of the 90s, and rode out the tricky 2000s with a honed ambition to make things work no matter what. Both as a DJ and producer, his sound is a potent distillation of New York’s music over the last 20 years – high-energy, often soulful, funky, and deeply immersive.

“During the 90s, you could go out no matter what age you were,” he recalls, “I don’t remember there being a thing about getting carded – it was kind of like the Wild West.”

“When I graduated in ‘97, I immediately got right into DJing in Manhattan. I had an older friend who was kind of my mentor, who was already quite deep into the scene, so I’d open for him.”

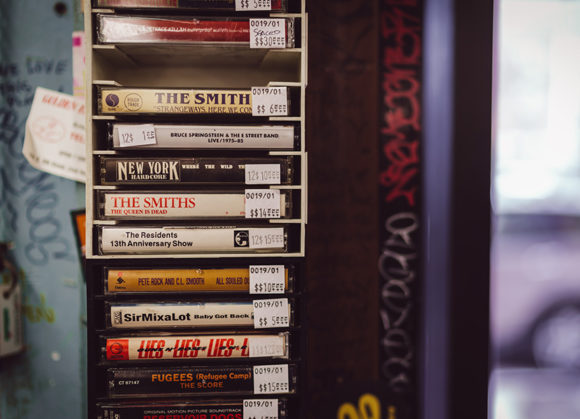

“I didn’t have a name as a producer, so I was just like ‘I’ll play anywhere, and I’m pretty good, I know a lot of different music.’ I wasn’t coming out like ‘I’m a techno DJ, if you don’t like what I play then you don’t get it, fuck you, no requests.’ I was like, ‘I wanna DJ, and I don’t want a day job.’” Escobar describes the sound back then as a “musical tapestry”: “Whether it was hip hop, or disco, or clubbier stuff, or house – all the music was pretty great.”

The eclectic, diverse sound that’s idiomatic of so many New York DJs is rooted in this part of the past – of DJs and crowds who weren’t afraid of mixing things up, and who would appreciate everything the city had to offer. It’s a journey that many other DJs from the city have made; taking influence from freestyle, hip hop, house, dancehall, and more, to cast the net wide and achieve a distinctive kind of sound and character you’d be hard-pushed to find elsewhere.

“That’s how I discovered I really love dance music.” Escobar says. He’d open up the hip hop floor at Vinyl on Hudson street, and then have time to see what else was being played. “I’d have the whole night to explore, and in the bigger room they had house, and I realised how warm and inclusive the crowd was.” This kind of cross-pollination was fundamental to the New York sound – “Nobody expected to hear one kind of music all night,” he says, “they’d probably get bored if they did.”

But after almost two decades it was in the new millenium that the going got tough. “Giuliani definitely came in with this goal of changing things around, but we didn’t begin to feel the effects almost until he left.” New York had seen this before: the 1926 cabaret law, originally conjured up to target jazz clubs in Harlem, was dug up, dusted off, and enforced as part of a draconic project to “clean up” the city.

“They’d start to send out the fire department to check up on things,” Eli explains, “the promoter would come up to you and say ‘they’re coming, turn the music down!’ And you’d turn the music down, everybody would go ‘Arrrggh!’ and then we’d sort of wait. Then I’d get the sign, and they’d be like OK, they’re gone. Go ahead!”

“I used to sort of look forward to it because it’d give me this opportunity to create some brand new crazy energy in the middle of the night. If you had the right record to throw on when it was time to get it going again, it was pretty awesome.”

But unsurprisingly, this would prove to be an unsustainable pattern for nightlife to survive, Eli explains. “Ultimately, the long-term effect was that throughout the 2000s things got shitty.” I cut my teeth during those years, playing five nights a week. I picked a bad time.”

Eli’s DJ career serves as a useful reflection of the New York scene’s wider resilience, and defiant “when there’s a will, there’s a way” approach to doing things. And while the 2000s might have had their bleak spots, where there were nights he’d say to himself: “this can’t be what I’m doing, if this is what’s going to happen I’m going to leave DJing,” the underground continued to simmer under the surface of a nightlife scene increasingly populated by bottle bars with table service.

“But then there were other nights… I was a long-time resident at Bungalow 8, and that was a fun party I did every week. There was a club called APT which was in the Meatpacking District when there was really nothing else there, which was really keeping things alive – every time you went, you’d see the same faces. A lot of friends were DJing and I’d DJ there. Cielo opened during this time too, and it’s still there, and that was sort of a beacon of hope.”

“And then I heard people talking about Brooklyn a little bit, and it seems so stupid now, but at the time it was too much for me to handle. I was like what? No! I’m not going to another borough to work or dance or whatever!” Escobar remembers. “I look back on it now and regret that I was so closed-minded. But for so long, the epicenter of club culture was Downtown, and it just seemed crazy to me that there would be something else.”

Even for somebody so entrenched within the scene, the shift to Brooklyn came as a surprise. “I started getting booked around the release party for M.I.A’s Kala. It was at this place called Studio B. I went, and was blown away – like I was DJing for a new generation of kids who weren’t going to the parties back in Manhattan, and they were super energetic. I hadn’t seen actual crazy dancing in a while! And I felt like everything had been so subdued in Manhattan, I really needed this. And that was the time of a new thing starting.

Escobar makes clear that there were still good things going on in Manhattan at the time – venues like the wittily-named Submercer, an intimate venue underneath the Mercer hotel, continued to push forward-thinking bookings. It’s clear however, that the nexus of dance culture had hopped the East River to its new home in Brooklyn. “And then it grew,” he says, “it grew fast, and now it’s insane. There’s a new club every weekend.”

It’s something Travis Higgins, whose Kaviar Disco Club parties have been populating rooftops both in New York and abroad, also tells me. “Back [in 2009] when I moved to New York there were so few clubs – there were like Avenue and Meatpacking clubs, and then hotel clubs. Fast forward to now, and there’s maybe three 1500-plus capacity venues that have opened in the last year, all booking electronic music.”

Like many others with a part to play in New York’s resurgence, Higgins came to the city from elsewhere. “There’s a good amount of locals,” he says, “but way more people come from outside.” This influx of promoters, DJs, and dancers, who never saw clubbing in Manhattan at its peak, might indeed have something to do with the scene’s Brooklyn explosion – having seen the borough as a relatively unexplored stomping ground for nightlife.

But, like anything in New York, competition is fierce. The scene’s current vitality is also partly the cause of its volatility – venues opening and closing their doors almost weekly are symptomatic of a highly-competitive market, where venues have started to jostle for the biggest and best lineups. When Output had its final blow-out on New Year’s eve, it became another venue that despite booking huge artists from across the world, found that money-wise, things didn’t make sense, and that it was better to go down with its reputation intact, rather than change the way it operates.

Part of the city’s tendency to birth leviathan venues and try to keep them under control could be to do with the legendary clubs of its past, although it seems unlikely that such an approach could ever be sustainable in the present given the way the scene has changed.

“When I think of the 90s,” Escobar says, “of clubs like Sound Factory and The Limelight, these were huge clubs. And thousands of people. They had the same DJs… everyone went to Sound Factory to hear Junior Vasquez, and it gave him the power to really make or break a record.”

“And now I think, like Panorama Bar [in Berlin] is one of the most influential clubs in the world, with different DJs every week. It’s great, things change and I won’t complain, but there won’t be the thing where you’re going to create specific memories of a song, like ‘Oh I used to go to Panorama Bar on Sunday afternoons, and they’d play that song when the sun came through the windows,’ because there’s always somebody different playing.

“I think that’s one of the great things about the 90s, and that’s why you get these big house tracks everyone can sing along to. I think if you’re really into dance music now and you look back in 20 years, it’s not going to happen. And it’s not because there are no good songs, it’s just the way everything is programmed.”

“I think people are realising it’s not just bookings,” Higgins says, “because it doesn’t really work – you need to have a built-in crowd.” It’s something Escobar says too: “I think the best thing you can do now is open something that’s not trying to compete, and just do your own thing.” The parties and clubs really leaving a mark seem to be the ones built on this mentality – places like Nowadays, run by the Mister Saturday Night crew.

And while things settle in New York, and the venues likely to go down in club history emerge, this becomes all the more important. “I’ve come quite close to telling people ‘you know, if you give me every Saturday night I’ll stop touring.’ Escobar explains. I’d rather have this thing I can invest in and harvest, where I maybe even leave behind some kind of legacy, than these endless two-hour sets where I only get into it 10 minutes before the next DJ is standing there with their USB sticks – it’s fun, and I know I’m lucky, but there’s something about having a weekly thing that you can put everything into.”

That’s happened, both with Higgins’ Kaviar Disco Club, and Escobar’s Tiki Disco. The latter started in a pizza restaurant backyard, with Escobar and his friends DJing for food and drinks, and became a regular event, with hundreds of people waiting to get in. It’s a perfect example of things growing organically, and leaving a lasting impression – a way to keep things going,

“I think there’s this misconception of clubbing that people have where it’s like, ‘oh you do that for a few years when you’re crazy and wild, but you never settle down with someone you meet in a club,’’ says Escobar. “And I think it’s the exact opposite, I think people I’ve met in nightlife are so much warmer and more open-minded and caring. I couldn’t think of a better group of people to spend your time with and to be around. I’m way over 30 and I’m still there!”

photo credits: DropkickJosh Photography