Composer Walter Mair has two studios. One is in London’s central SoHo district. “It’s bare bones, like a big projector and a couch,” he says. “It’s more about making the directors and producers feel comfortable.” Then there’s his home studio, which is anything but minimal. It’s a mad lab anchored by a giant modular synth rack and a range of keyboards – a Flock Audio PATCH system and a MASCHINE both allow him to control his outboard gear and transport MIDI to and fro. Mair has custom instruments (including a modified piano, an OctoBass, and a ContraHurdy) and holding it all together is a Mac Pro with 16 terabytes – running Logic software and crammed full of software and plug-ins – all connected to an Apogee Symphony I/O Mk II audio interface and Focal SM9 monitor speakers.

Mair loves to experiment but he’s also usually on deadline, crafting soundtracks for movies like Till Death and The Unfamiliar as well as videogames from Call of Duty: Mobile to multiple titles in the Grand Theft Auto series, sometimes with only hours to spare from temp score to finished cues. Yet his workflow is anything but predictable, using everything from string quartets and full orchestras to custom KONTAKT instruments, modular sounds, and all manner of unsettling bass, gurgles, and stabs from NI synths like REAKTOR, MONARK, and MASSIVE. He’s not a purist, but a processing king – unafraid to apply digital effects to pristine “real” recordings and vice versa. Nonetheless, he says his creative spark usually comes through his eyes not his ears.

“I can’t work without any visual input,” explains Mair, who was raised in the classical epicentre of Vienna, Austria, but calls London home. “I love seeing anything – it could be a creative artwork, an assembly or even just a drawing by the director. In reading a script, I find sometimes there’s too much room for interpretation, but as soon as I see one frame, it triggers something in my brain. It’s intuitive intuition, you know? It comes from all the music I listen to in my spare time, the stuff that I built myself that never gets released… All of that influences the way I write to picture. There might be a temp score and a director might brief in a specific way, but this first impulse is usually the right thing – there’s a kind of intention there.”

Recently, Mair sat down with Jan “Kabuki” Hennig, a Frankfurt-based producer and Native Instruments product specialist, to talk about how he uses modular synths with MASCHINE, his favorite NI synths, creating custom instruments, and scoring everything from horror flicks to action games. Read to the end to get his advice for new composers, plus hear five of his favorite musical cues and find out how they were crafted.

I see these two worlds you’ve got going – on one hand, you’re into quirky synths, like the OP-1 and the big Arturia Polybrute, and you’re also doing a lot of live recording of full orchestras and string quartets. Where do plug-ins come in to play, and what VSTs do you enjoy working with to alter sounds?

Walter: For me, there’s not much difference in terms of a digital or analog source. It’s just about “What should the sound actually sound like?” For instance, very often brass in a demo sounds quite gnarly and biting. It’s wrong. And then you record it live and it’s absolutely amazing – it has the depth and width, but it doesn’t have the tiny bit of extra bite. So you find yourself using something like Soundtoys’ Decapitator, just to give it a bit of an edge. I just recorded a few piano notes for a job and I used Guitar Rig to create these endless, quite brilliant delays that pop up with a shimmer on top. Then I added distortion and it sounded fantastic. I could never program something like that in the first place. It’s just something that happens when you use the simplest motifs and melodies, enhance them digitally, tweak a few faders and the sound that comes out is insane.

I usually only have a window of a couple of weeks to creatively experiment. During that time, I try to do anything but writing the entire cues – sometimes I write a suite, and then you have elements and motifs in there you can use. The rest is just hard work, using what I’ve done in the first week or two and making sure the rest of the score develops. It’s all about the creative spark. Where do you find it? How do you get it?

In making the music for the recent thriller movie Till Death, you employed waterphones and field recordings. Can you tell us a little bit about the creative spark for that score?

There was a tiny bit of temp scoring there, just to give me an idea. Horror can be quite kitschy at times, so I was trying to move beyond that. Emma (Megan Fox) is out there in the snow in this winter landscape in her cabin, some events happen and everything goes south. I thought, “What can I do to enhance the winter landscape? The leading sound designer at the post-production place reached out to me and was like, “Hey Walter, I’m sending a foley artist to Finland to record some cold, winter landscape sounds, like atmospheres and wind.” I asked him to add a couple elements to the shopping list for me – like a recording of somone throwing a rock on a very thick frozen lake, which doesn’t make a bouncing sound, it just makes this “krssss.” It’s truly like the laser sound of a Star Wars trooper! I asked if they could record a gazillion of those. Big rocks. Small rocks. I need guys to take a huge axe and try to smash open the ice and snow. They also experimented with dry ice, which sounds insane, especially close mic’d. So I got back this huge library of sounds. And the Star Wars trooper sound from the lake, if you use that and pitch it down two octaves and stretch it using the algorithm – or use the Morphogene or Nebulae in the modular synth rig and stretch it out by 600% or 800% percent – out comes this woooorrr orrrrr [makes deep monstrous warble sound] and that forms the basis of a pulse that goes on in the background. And because it all originated in a live recording, there’s always some authenticity to it.

Using the DNA of the landscape… That’s a very interesting way to transform a sound from one function to the other.

Totally. You take the field recording or instrument out of context and tweak it and out comes something different, but there’s a link in there and you can feel it. Emma is in a constant state of fearing for her life – there’s something in there that’s very off, and I wanted a sound for that. I thought, “How about we use double bass?” That instrument captures an emotion that is quite low and dark and I wanted to combine it with something more electronic, but quite organic. I reached out to a friend of mine in Austria, Thomas Mertlseder, who is a sound designer and instrument maker. He takes a contra-bass and a hurdy gurdy, which is like this medieval kind of instrument, and he goes into his shed and does his thing and comes out with the contrahurdy. It’s the double bass – which quite a hefty instrument with big, thick strings – but then on top, instead of a fingerboard, there’s bolts from the engines of the hurdy gurdy and as soon as you turn it on it makes this brrr big bass noise. It creates these really interesting overtones and it’s such an amazing thing that I’ve never heard before – it’s just one of these Frankenstein instruments.

How did you go about sampling and transferring the contrahurdy sounds into KONTAKT?

In that case I just played it live in what I call chunks, recorded them, and then dragged them into Kontakt. Each note or half-note would be a different sample (you can play on the keyboard) and they’re at different pitches and stuff. It has this disorganization to it but I really like it. I picked one sound to be the lead sound. And then I asked a friend of mine to take on the programming work and we did that same process of making a Kontakt instrument with the waterphone, which is not chromatic instrument, you can’t play like C, C sharp, D. There are limits and those limits are actually quite good because they reminds you: this is not supposed to sound good. [laughs] It’s pretty gnarly and it fits this foreboding feeling that something’s going wrong.

Very often I sample stuff myself, even if it’s with an instrument I can’t play; I might play something wrong or out of tune but it sounds so auditorily satisfying. It’s about finding a unique sound for the project – and even if it’s “wrong,” it could still be right.

So we have your bespoke instruments, some of which you sample and make into KONTAKT instruments, then these live recorded score elements. At what point does MASCHINE come into the equation?

I use Maschine often for rhythmic parts – if there’s anything I would like to play with my hands and get a feel for the rhythm. I love the pads, they’re super soft and I like the organic texture they have. If it’s something I’d like to play on Maschine rather than a keyboard, I don’t go to lengths to program it into Kontakt; I just import every sample into Maschine or Battery and its super easy to tweak sounds in there and pitch them up or down. If it’s a percussive element, which has a very short transient, then you have to quantize it a tiny bit so it fits to the metronome. If you have sounds in there that aren’t percussive, then maybe you leave them. Maybe you go to a factory or you smash stuff and there are sounds with a long transient or attack or decay. How do those sound when you played them back, or even play multiple sounds on top of one another? Some stuff shouldn’t overlap but when you trigger it together it creates a nice sound. Maschine is so straightforward, you literally play it – it’s like playing piano to me.

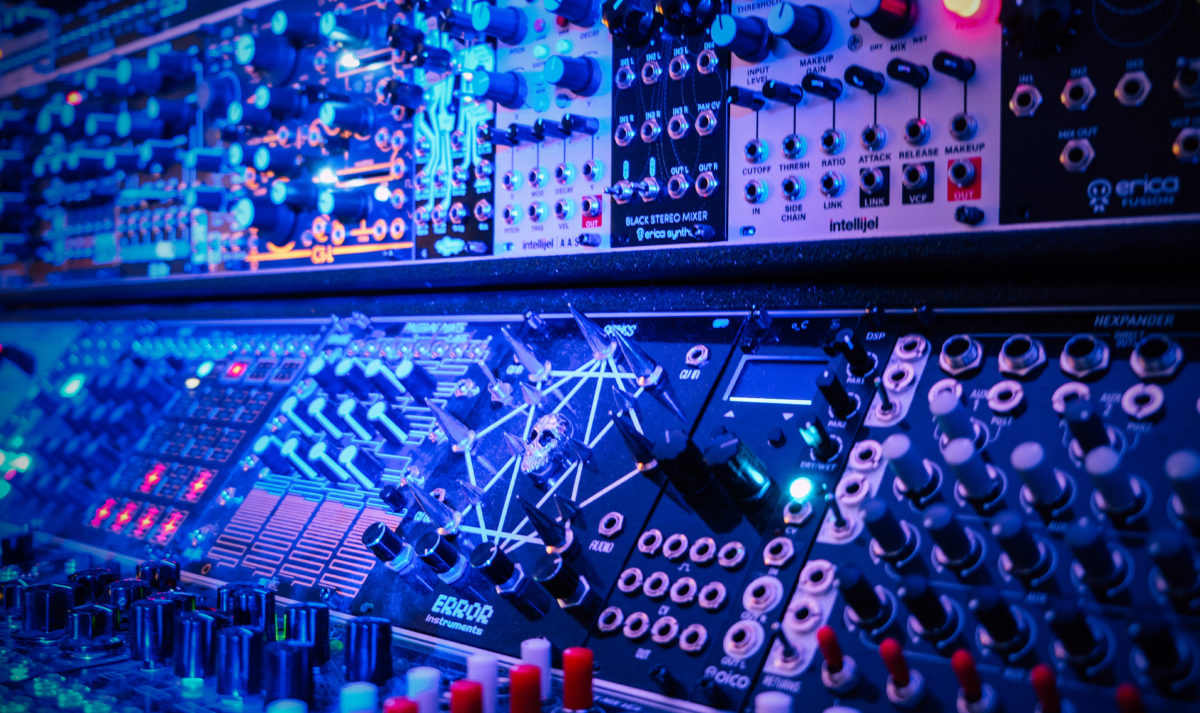

The modular rig plays a big part in your sound. Do you see the modular synthesizer as one big voice or how do you think about it?

It is like a big mouth. You feed something in and something comes back. For the longest time, I used it as an internal kind of process, where there’s an oscillator going into a filter going into an effect or an arpeggiator – then you record that and it becomes the first part of the jigsaw puzzle that’s a track. Then I decided, wouldn’t it be nice to feed in sounds from the outside world? Then I got Qu-Bit’s Nebulae module. You get your tiny USB stick, you put some sounds on it, fire it in, and then you can stretch and cut the sound in all these sort of granular ways, which I love doing. With Nebulae, you can change the pitch and the lengths independently. I did quite a lot of sound experiments in that. In the last year, I discovered I would like to use a source coming from the outside that triggers the modular instead of the modular triggering itself. Now I can prepare the perfect structure in Logic, fire MIDI into the modular, and trigger new sounds I like within there. Then I discovered that I could do the same thing with Maschine because it’s got MIDI outs. So I run MIDI through Maschine and when I play the Maschine pads it triggers the modular synths.

You seem to be quite into the whole granular side of things. Have you experimented with some of the Reaktor patches that deal with that, like Travelizer?

What I use a lot is The Finger and The Mouth from Reaktor, and Rounds inside Komplete. Very often I use the iPad – there are some granular synthesis things on there which are really cool tools, like Samplr and csGrain.

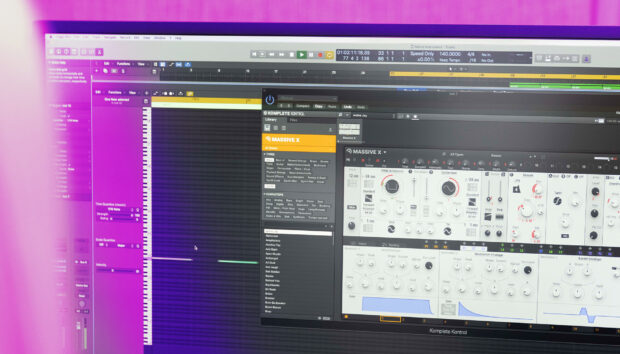

I would love a new iteration of Absynth. It was my most used synthesizer for so many years of my earlier composing life. Absynth has such a huge versatility in what it can sound like and I program the most ridiculous sub-basses in there. It’s got really tiny, granular-ish pads that are super sophisticated. I used the ES1 and ES2 [built-in Logic synths] quite a bit in the beginning, but now I use Monark, which is so simple and straightforward but also goes quite deep – it has so many cool sounds, especially bass and ’80s sounding arpeggiators, Stranger Things-style stuff. I love Massive for the sound. It’s a brutal sound, and you don’t need many effects on it. Sometimes you need just one synth sound that really jumps out and it’s perfect for that.

It’s about finding a unique sound…

Even if it’s “wrong,” it could still be right.

I use presets often as a starting point. You use a preset because it has a certain kind of sonicality to it that you like, but then you want to make it your own. Hopefully by that time, I’ve messed around with it and I know how to program a few parameters and go into the matrix and get to a sound that’s different. But at least you had a faster start because you didn’t start with an empty patch.

You want to be inspired, but sometimes you have to do exactly what needs to be done because you’re against the clock. Tomorrow, the client needs to hear something, and I have two hours time, or maybe eight hours if my client is in Los Angeles! These days I have my own library of patches I’ve designed for myself in Monark and Reaktor and I’ve got my own environment – let’s call it a “chain of effects” – for putting a sound through. Usually that’s something with a granular sound to it and then distortion, either before or after, and then a spectral delay inside Reaktor. Recording a quick take of a cello and running it through my chain is much faster than powering up a modular rig. That’s kind of my fuel to create something that gives me a very immediate output. It doesn’t sound better or worse, it’s just kind of that [snaps fingers] you’re there.

It’s very textural. You bring out components in the sound.

It’s a kind of Brian Eno approach. What I record is quite dry by default, so whatever I have here (other than something like the waterphone) is quite compressed. And if you run it through those effects it gets this three-dimensional character. Sometimes I mute the original and just use the pads to have something else up in the front, or at times it’s okay to have the mids like 50/50 or 40/60 with the original signal.

I was starting a track with some piano and I wanted to sample a very old piano I have that sounds amazing and then put some character on it. Eventually, I just found NI’s Noire piano and it sounds so good, plus it has stuff like the “space bubbles” in the Particle Engine, where you play a few notes and it just triggers something. I decided to mute the original notes and leave just the particles, then recorded the melody with my home piano – that to me was the perfect mixture of analog and digital, taking the best of both worlds.

It’s definitely a different approach to a person who uses pianos like Maverick or Alicia’s Keys — which are there for a good reason and sound amazingly real. I’m mostly trying to push the boundaries and think about how I can use this stuff to create something that some people haven’t heard before; doing something that goes the extra mile, which I think is the reason why directors and producers come back to me in the end. I’m a big sucker for Native Instruments, I have to say. I’ve been using it ever since I entered the music market, since I became a composer, so it’s in my DNA.

You’ve also worked on a lot of videogames. From an emotional aspect, is scoring a videogame different to a film?

The way of working is very different, but the emotions are the same. You have to be very true to whatever emotion the filmmaker or game developer wants to convey. The way I write for games is in three or four-minute long tracks – let’s say, you’re walking through the corridor, there’s tension, this crosses over to a fight with one enemy, then you’re retreating, then going back at it, then there’s the final boss fight. All of that needs to be in the back of your head, which makes it a bit more difficult from a logistical point of view. But I love this challenge. My music gets so much more dynamic than I ever had in mind because it’s triggered by the game.

When we worked on Crash Bandicoot, I had just come off The Unfamiliar, which was a gritty, dark psychological horror film. I was in that world for many months and it was good fun but I wanted to do something that would evoke different emotions in me. In came this pitch for Crash Bandicoot 4: It’s About Time and I thought “This might be exactly what I’m after.” Happy, positive, in your face. It’s got different universes: there’s an ice world, a world of dinosaurs, ancient times, science fiction, the future. I did an electronic guitar-wave track in there; I played some prehistoric bone flutes that I sourced. There’s a Mardi Gras level where the player jumps from a piano to a tuba, and wherever you land triggers a different note and phrase. It’s all based on beats and the player has 100% control – you can’t wait for a half a bar or something – but it doesn’t matter and it still makes musical sense. It’s clever writing, but even more clever programming. It was such a big ambitious project and it worked out brilliantly, and it’s one of the best areas in the entire game. You always learn something from every project; there’s always something you can take away as an experience.

What’s your advice for composers who are just starting out?

Record as much as possible live. It could be drums, it could be something you play – it doesn’t matter what it is. I encourage everyone to record live, structure that, build a Kontakt instrument – make sure those phrases are with you and you can use them again and again. It becomes a part of your sound and your palette and style that no one can take away from you. For years now, I have recorded strings and I usually try to do a few recordings at the end of a normal session, some aleatoric stuff, something quite out there. Now I have those recordings in my library to use for initial sketch demos.

Also, learn not to overproduce. It’s something that I had to learn over many years and still have to learn. Sometimes I have 15 reverbs on one sound and there’s no point in doing that – very often it just messes up your frequency spectrum and eats everything up. Today you have every synth and plugin at your disposal, so its important to get to a point where you carve out space for each frequency with an EQ and make sure all your sounds are there for a reason.

Keep reading below to find out about five of Walter Mair’s favorite pieces of music he’s composed and how they were made.

“Hold Your Breath” from Till Death

Till Death is quite a sinister, dark action film. In this scene, Emma (Megan Fox) is being chased by our antagonist and this is the pre-showdown. We’re on a frozen lake, there’s no way to escape, you can see blood on the white snow, everything is building up to the big moment at the end. The music had to be quite weird and textural, to show she’s in a frantic mental state. There’s a big payoff moment at the end of this sequence where she had to convey quite a few emotions very quickly and it had to be punctuated by music. The entire scene is gnarly, dark, and menacing so the music couldn’t be four-to-the-floor and structured — I knew I would have to go off the grid. I recorded quite a few drums and percussive elements, which I fired off using Maschine – literally me hammering on the pads to program beats in a way that you wouldn’t normally do in your DAW (where everything is quantized). It was off-kilter and organic and I was really able to score to picture, which I don’t do very often because usually everything needs to be looped in bars. I also used the contrahurdy instrument that I discussed earlier, which is a Frankenstein instrument of a hurdy gurdy and a double bass. Again, I recorded it and built a Kontakt instrument, which fires off phrases that I can pitch up and down, and I also used Battery to truncate samples, like percussive hits.

“Finale” of Till Death

This is the finale where Emma (Megan Fox) is trapped under ice. She’s not able to escape at first and there’s a big struggle. I needed something quite fragile, so I recorded with a string quartet first, which gives us the clarity and the intimacy. Then I recorded weirder strings on top that are doing these extended play techniques, like using the wooden side of the bow – it sounds quite screechy and unpleasant.

There’s four elements in there. There’s the contrahurdy, which describes the entire scenery of the film, and the waterphone, which represents the lake and the sense of the coldness. Then I’ve got the electronic synths, which have a propulsive movement like an undercurrent; some came from Monark, some came from Reaktor patches. I modified them to make them go in and out of tune, so nothing is as pleasant as you think it’s going to be at first. What’s left is the strings – the emotional component – and as soon as those elements come together, it’s a big finale. There’s dozens of layers that form this composition – deleting elements is not necessary, it’s just a matter of carving out EQ curves to make sure each instrument can stand on its own. All of that came together to create this emotional payoff for the end of the film.

Call of Duty: Mobile Theme

Call of Duty is such a big thing, and mobile is a new part of the franchise – this music needed to be as big and epic as humanly possible. I needed a hero for the theme and for that I had a cello playing the lead parts, recorded live together with brass. After that I did some percussion which I played live, followed by drums, bass, a guitar, and synths. I used Massive for some of the synths and sound design effects. Call of Duty is a huge platform so it needs to speak to everyone. There’s guitar and post-rock stuff in there, electronic, and the big brass and orchestra – it’s a good mixture of elements.

“Opening Theme” of Three Way Junction

Three Way Junction is a film shot in London and the Namib Desert in Africa. It’s about this guy whose car breaks down and he’s stranded in the desert, left to die there with no one, the sun is glaring and blistering and there’s no way of escaping. In the beginning, I had to capture the beauty of the environment along with the impending stress; I was thinking about the sun, which is actually there to help us survive but in this case it was taking away life. I recorded a few layers of strings – the biggest layer is very cool with alternative extended-playing techniques. I made these evolving strings which mutate and change texture throughout time, and then came the melody on top and the piano. It’s more of an orchestral, organic score, with a few underlying synth pads. It was an amazing experience because we recorded at Abbey Road Studios in London and the musicians were the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, one of London’s best. That was a career highlight – it was just amazing to have the opportunity.

The Heist Theme

The Heist is a super cool film directed by Tom Green, who also did Monsters: Dark Continent. The decision was made that the score would be as electronic as possible. It starts at the big bank robbery scene, which is epic and beautifully shot – each frame looks so amazing. I knew I had to give them my A-game, using the best synths possible. I used quite a bit of modular, modeling software, plugins. I even brought back Absynth because I like how it granulates and how it works with sounds.

I realized it would be nice to have some incoming and outgoing strings, so I recorded a small section of just a few strings. I cut those pieces together so when something happens in the film, one string always goes up and the other always goes down – the medium is static but there’s always a counter movement in there. Then I thought, “How can I still add to the feeling of nausea, and not knowing what’s going on and where we are? It’s been crescendo-ing for five minutes. What happens now?” That’s when I brought in the Shepard Tone, which Hans Zimmer used in Dunkirk. It’s this upwards-moving synth where the bottom is quiet and then it gets louder and vice versa – it creates the illusion of a constantly rising note, the perfect illusion of an infinite crescendo. The Heist is mixed for cinema in Dolby Atmos using 64 channels, and when you hear it like that it becomes even more enhanced and stronger so it gets really weird!