Mongolian warlords. World-class ballet dancers. Ants in the Sahara Desert. Shaun the Sheep. Coldplay. The Sims. In a Venn diagram, these things don’t have much in common, except Ilan Eshkeri. At 43, the British composer has spent over 20 years soundtracking both the grand and the mundane with equal care and feeling. Eshkeri’s work runs the gamut between film, TV and video game scores, orchestral arrangements for the likes of Amon Tobin and Coldplay, and more esoteric commissions, like a 12-part tone-poem for Paris’ Tuileries Garden and music for astronaut Tim Peake’s Principia space mission.

“It’s all a story,” says Eshkeri. “Whatever you’re making music for, even if it’s just a dance track, it’s very helpful to think about what the story is and doing things that are in service of telling the story. Even if you’re conveying an abstract emotion, it can still have a narrative flow. Lots of people are focusing on just making music, and if you’re scoring, that’s not really the job. The job is storytelling.”

Eshkeri was brought up on classical music – he’s played violin since age 4 playing violin and electric guitar since 13 – and unwittingly honed his chops sitting in on practice while his mother worked with a charity orchestra. “I used to spend every Thursday night doing my homework while a 90-piece orchestra was rehearsing,” he explains. “I’d sit in different places – at the front, back, side – and I got used to knowing what these different instruments did. Now I have a very clear sense inside my head of what the orchestra sounds like and what it can achieve. It’s useful to know where the instruments are most resonant, and what keys work best for different instruments. For instance, B flat is a bad key for strings but a great key for brass. People think, ‘Oh my god, it’s so big and hard to learn,’ but that’s just the myth that people have created to make it seem inaccessible. There are four string instruments, four brass instruments and four woodwind instruments, and then versions of those. It’s 12 instruments! You could learn that in a week by Googling it or looking on YouTube. Learn the instruments and learn what they can do because the samples only tell you 10% of the story.”

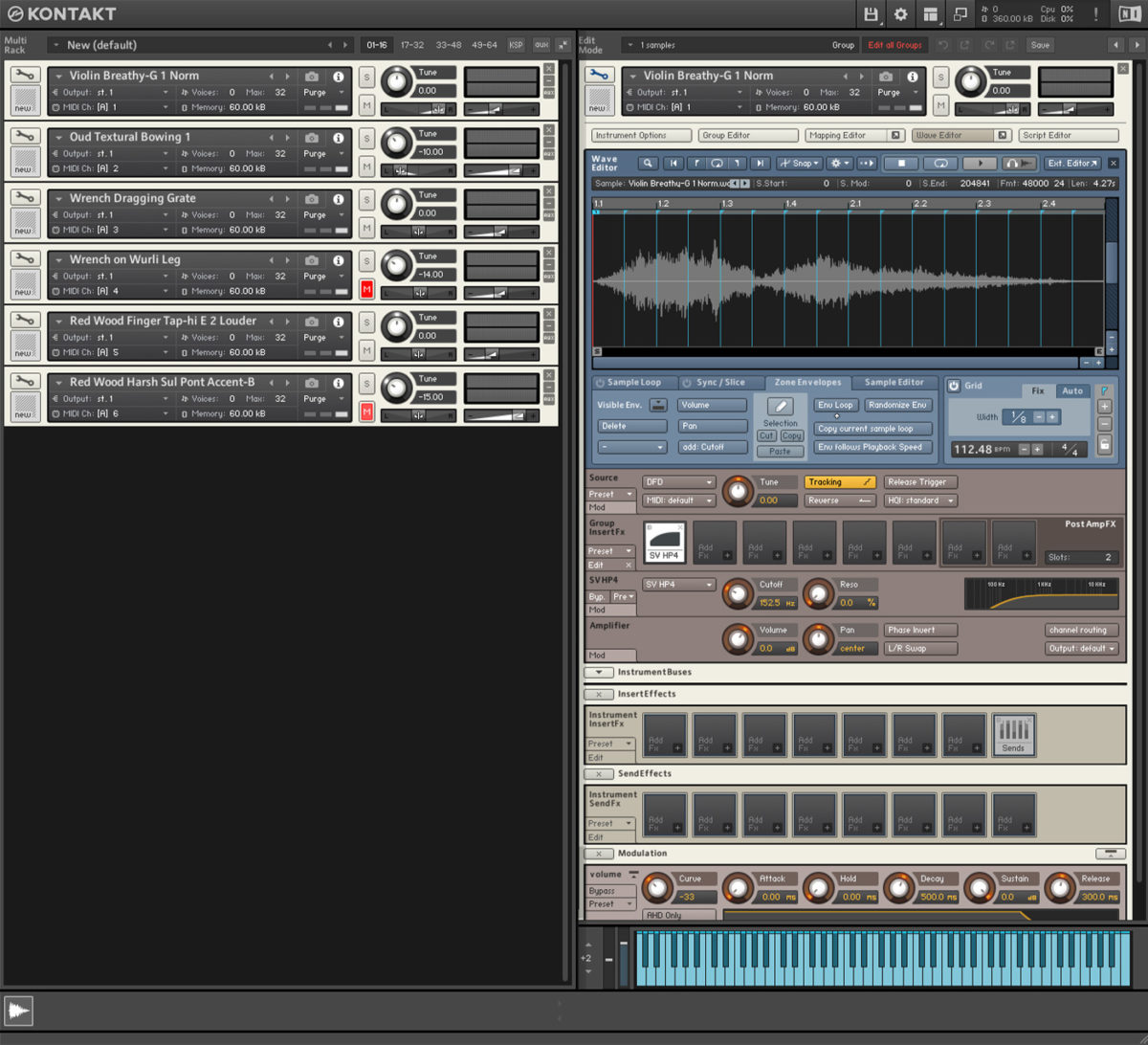

Sounds Eshkeri recorded and turned into samples using KONTAKT.

Samples may not replace an actual orchestra, but they are a huge part of the modern scoring process, explains Eshkeri, who began his career at 19 working for British composers Michael Kamen and Edward Shearmur and spending summers at London’s famed Abbey Road Studios. “When I started, people were still recording on two-inch tape and Pro Tools was the new thing. I had to work out how all the new digital equipment worked for the composers that I was working for. At that time, sampling was still in Emulators and Kurzweils, and Hans Zimmer was just beginning to evolve that whole world into something bigger and greater than it had been before with recording his own samples. Soon after, Gigastudio happened, which was a computer-based sampler, and then shortly after that’s when Native Instruments came in with Kontakt and it’s been that way ever since! But the industry went through this change during my 20s where suddenly a piano sketch wasn’t good enough and clients expected you to create a full symphonic mock-up.”

What you hear increasingly is orchestral scores that sound like the samples, and that is through lack of education. So I encourage everybody to learn what the orchestra can really do.

“The good thing about working with the computer in general is that it turns you into an audience member,” he continues. “I can try out a piece of music, sit back and listen and decide whether I like it or not. I can save another version, or try something else infinitely.” Mockups made using VST instruments are shown to film directors or whomever is commissioning the project for approval before they make their way to musical notation and on to live players. “The sample is a tool to get you from one place to the next,” explains Eshkeri. “And that’s why I use the Kontakt sampler all day, every day, as part of my process – it’s very interactive and easy to use and it doesn’t get in the way of my creativity. It’s got great complexity, if you want complexity, but if you just want to do something really basic and simple, you can do that super quickly. And so that makes it a really versatile and useful tool in the studio.” Eshkeri is particularly a fan of Kontakt’s drums, the timpani and celeste from the Symphony Series and creating his own Kontakt instruments with samples he’s recorded from live instruments.

Ilan is still a strong believer in taking things out of the computer and having real humans play what he’s composed, or at least mixing the two. “There’s a lot of complexity now in the way that people use virtual instruments, and expectations of what can be done. But with everything I do, I always make it real. There’s a tremendous amount of pressure in the industry to do things with samples, but I think you need the performance. You need the heart and the soul. Art, at its foundation, is about authenticity. Without authenticity it has no value. And I think the other real danger with samples is that people start writing within the limitations of the samples instead of the instruments. What you hear increasingly is orchestral scores that sound like the samples, and that is through lack of education. So I encourage everybody to learn what the orchestra can really do.”

Ilan is quick to explain that he doesn’t mean he can afford an orchestra on every project. “A lot of times I can’t! I did a film with Ralph Fiennes where we just did everything with a solo violin and a solo cello. There was a huge train crash in it and it was like “How do I score a huge train with just the violin and the cello?” But it’s all about creativity. Often the limitations are what force you to do something interesting.”

No matter how large or small the project, Ilan always starts with a vision and a framework. “You need an idea. And that concept becomes a construct around which the music is based, which helps give it purpose and significance. When I worked on the videogame Ghost of Tsushima, that was all about authenticity and Japanese music. I decided to work within the framework of Japanese harmony, which was complex – in Western music, you have a 12-note scale, but in Japanese music, you have different types of 5-note scales. If you work solely within that harmony, which they did for a thousand years, you’re quite limited. And that was very challenging. I kept thinking, ‘How am I going to make Japanese instruments fit with an orchestra?’ Then I thought, ‘What if the Western orchestra only played within the confines of Japanese scales and tonality?’ Traditional Japanese music is sort of homophonic; they don’t really have chords and harmony in the way Western music does. So I devised a system of chords that were built out of 5-note scales. I created this process of writing music, and then once I’d created all the rules, I broke the rules all the time!”

Eshkeri didn’t just study Japanese music from afar for Ghost of Tsushima, he immersed himself in Japanese culture and traditional music. “I used shakuhachi, biwa, taiko drums, a whole load of percussion, koto, Japanese chanting Japanese solo female vocals, a Japanese flute called the shamisen. They typically wouldn’t have been played together very much at all so that’s how I used them, in a soloistic way. The musicians I worked with were really extraordinary and extremely patient – they really took the time to talk to me about the instruments, how they’re played, what’s stylistically unique to them. For instance, the koto (a zither-type plucked instrument) plays these five notes across two-and-a-half octaves; you can alter the scales, but not during the performance. You can bend a note a quarter-tone, sometimes the lower notes you can bend up a whole tone. And that’s it – that’s the limitation. Whereas a shakuhachi, a Japanese flute, is different – you can underblow the note a semitone or overplay the note a half step; if you overblow a whole step, it’s too screechy. And then of course in your sample library, the sample comes up and it plays every note of the scale – it’s easy not to consider what’s actually possible, but in this case I wrote specifically for the instrument and what it could do in real life.”

“The instrument I loved the most was the satsuma-biwa, which was the instrument of the samurai, they used to play as part of their epic storytelling. The art was nearly completely lost but there’s this incredible woman, one of the most soulful and the most amazing musicians I’ve ever worked with, named Junko Ueda who plays it and taught me about it. There’s this piece of music on the Ghost of Tsushima album called “Forgotten Song” and the melody is a shomyo Buddhist chant that Junko Uedo sang for me. I used the melody and arranged it and had it orchestrated. But that melody is over a thousand years old, it’s ancient, and it sort of pierces my soul whenever I hear it. The great thing about art is that there’s a point at which, it’s not just notes, it’s greater than the sum of its parts. It has some meaning and it carries weight and history, and that connects deeply on some level.”

4 cues that KONTAKT helped create

“I create my own samples often. In these pieces below, you can hear things that I’ve recorded myself that I’ve used. Again, it’s all about not getting in the way of the creative process. I make a sound, I’ve recorded it, I want to get it into the sampler really quickly and work with it. I want it to be as simple and direct as possible, and Kontakt is really good at that.”

“Way of the Ghost”

“This is the theme tune for Ghost of Tsushima, and it was one of the first things I wrote. We put it on the back burner because we weren’t sure, but then it came back and I’m glad it did. It’s a very simple tune – it uses a five-note Japanese scale, and it only uses those five notes in the entire piece. At the beginning, there are these drones… The biggest part of the drone sound is me playing on a very particular place on the violin in a certain way with a bow that I’ve specially treated, then putting that sound in a sampler in Kontakt and using that sound throughout the score. The sound is very quiet when I initially play it, but when you slow it down just a tiny bit in the sampler it really brings out all these artifacts that the bow creates; then you put a bit of reverb or delay on that and turn it up and it just creates this very interesting sound field. The drone comes at the beginning and the end of this piece, and it just creates a very sort of rich sound bed.”

“Khotun Khan”

“Characters typically have their own motifs or melodies and this is the theme for Khotun Khan, the bad guy in Ghost of Tsushima. Again, I created a sound on an instrument and sampled it into Kontakt. The instrument is something I picked up on an island in Malaysia many years ago – I call it the Redwood – it has a big thick neck and a tiny drum of snakeskin on the bottom; you play it a bit like a cello. It has three metal strings and over the years, one of the pegs has broken so I can’t tighten that one string. So I took my violin bow and as I bowed it, it pulled on the loose string and changed the pitch of it; when the string was released, it made this rrrrrrang sound. I put this sound in the Kontakt sampler and played it down from its original pitch – about five notes or so but still in key – just enough to bring out these really interesting artefacts.

“I loved the sound so much and so did the game-makers that I started thinking, “How can I write this so that the orchestra can perform this sound with the whole string section or the whole brass section, so that they can make a sort of giant representation of this sound?” And so I set about trying to work out how to write that in notation – lots of black scribbled-in triangles and stuff on the paper to try and get the orchestra to do it and we got there in the end. So now, every time Khotun Khan is by himself, he gets this sound of me playing the Redwood instrument and sometimes when he’s standing there with his whole army, you get the version with the orchestra. I think it ended up being quite effective in the piece, and Kontakt was very helpful in that journey.”

“Silver Ants”

“The silver ants are just amazing. They live in the Sahara Desert. When the sun comes out and it’s becoming too hot, and all the animals are finding somewhere to hide, the silver ants run out at the last minute to try and scavenge for anything they can – a carcass, an animal that’s not gotten away or that might be dying. But they’ve got an incredibly short amount of time before it gets so hot that they’re also going to die so they’re right on the clock. I watched this scene in the series and I was like “This is a heist movie with ants.” They’ve got 10 minutes to get out there, find some food and get it back and stuff goes wrong along the way and there’s all kinds of challenges they have to overcome. It’s just brilliant. The music had to be really high octane right from right from the start so I thought, “How would I approach this if it was a heist movie?” I thought I’d use a lot of synths – a Juno, an Arturia MiniBrute and a VST that’s an Oberheim replica – but it also needed an organic element because they’re ants so I played these really fast elements and also some scratchy sounds on my violin and put those in the Kontakt sampler. I could have re-tuned the whole violin to get the sounds, but it was useful to be able to record it in and then move it about in the sampler. It’s all synths and solo violin and a little bit of percussion (that also ended up in the sampler) until the end when the orchestra joins in. I approached each animal’s section like a song. My challenge was to actually make these feel like individual tracks and not a film score, which is unique for a nature documentary. Virtually all of the tracks have a pop element to them; everything has to have a big melody always and within that you’re telling stories that match the animals and what environment they live in.”

“A Perfect Planet”

“’The story of Earth’s power and fragility” is the tagline for this series and the main character in it is our planet, Earth. In the series we learn about how Earth has provided the climate for all life to exist so I wanted to write this theme around the idea of Mother Nature – I thought the best way to express that was through human voices. In the series, you’re somewhere in the world with an animal character, you zoom out to the planet and then you get this vocal theme; if you zoom out to space, you get the same theme but played on piano, very simple and distant. Often these types of nature shows don’t have a constant theme we keep returning to but in this show there is one – sometimes it’s a major version, sometimes a minor version, but it’s always vocals, piano, arpeggio strings, or a combination of those; it gives it a real sense of something dramatic. Loads of different people performed on it: Tim Wheeler from Ash plays guitars on it, Tim Carter from Kasabian plays drums on it plus a brilliant composer and vocalist named Chad Hobson, an up-and-coming folk singer named Daisy, also several children’s choirs sang on it and a professional adult choir. The first two episodes were recorded in London but after that you couldn’t put an orchestra together during the pandemic. So my friend Atli Örvarsson, who is an amazing composer, conducted the strings for me in Iceland. That’s the point of the whole show is the planet collaborating – it’s about people coming together, and hopefully taking climate change and sustainability seriously enough to make a change.”

Ilan’s score for A Perfect Planet is available now. Check out your options for purchase or streaming here.