With his new single “Dust” on All Day I Dream’s Spring Sampler, UK producer Jim Rider continues to refine his deep, melody-driven club sound. Known for balancing emotional tone with tight, effective arrangement, Rider brings a kind of self-editing clarity that many producers spend years trying to develop.

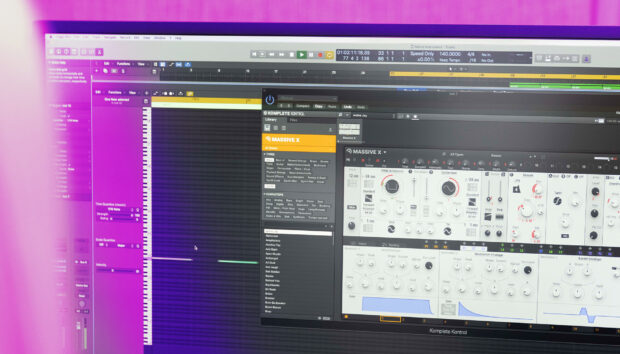

That mindset is especially visible in his use of Native Instruments Massive, a synth known for its endless modulation options and deep control. For Rider, the challenge isn’t how much you can do in Massive – it’s knowing when to stop. His patches are built around purpose, not complexity, with most of the magic happening through timing, automation, and carefully selected movement.

In this interview, Rider explains how he avoids overdesigning his patches, how he uses macros and subtle automation to keep sounds interesting, and why simplicity nearly always wins.

Jump to these sections:

- Techniques for stripping a busy patch back

- Why he prefers musicality over heavy modulation

- His performer + macro tricks for movement

- The importance of restraint in sound design

- How “Dust” evolved through subtle edits, not complexity

Here’s how he keeps a synth like Massive musical.

When a patch in Massive feels too busy, what’s your process for scaling it back?

I suppose it depends on what the patch is going to be used for. If it’s a lead synth or arp it can afford to be busier, more varied and take up more space, but if we’re looking at a bassline or a pad it may often be better to simplify it so it doesn’t distract you from your other elements. If something feels too busy I’d usually strip it down to its lead oscillator and work “up” from there. Over-layering is easily done in Massive as there are so many “controllables” and it’s easy to get carried away.

If a texture is a bit much, I’ll solo everything until I work out which bits are “busiest” then start muting elements. Usually if too many things are working simultaneously it becomes overpowering.

Like most people, I use Massive for a lot of basslines. I know this sounds like a really simple thing but it’s effective; I like open up the cutoff at the end of each phrase (e.g. into breakdowns, drops or when introducing a new element or melody) to let the listener know something different is about to happen, then when you’ve made your point, you just close it again to get back to that fuller bass.

I’ll also sometimes just steadily open it up throughout the track, it’s subtle but increases the energy as a track evolves.

Honestly though, sometimes they’re just best left alone. I used the “Baby Cybermen” patch in a recent remix I made of Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn.” I knew I had the patch and melody I wanted, so I dicked about with it for hours (and got nowhere). I ended up literally just resetting it and using the preset with some very minor tweaks. So I guess initial sound selection is just as important as trying to tame a patch.

Have you ever had a moment where too much modulation ruined the groove or tone of a track?

Yeah all the time, quite often you want to squeeze every cool sound you’ve made into a track but with age and experience you come to realise less is more.

For example, you could make a bassline with an envelope on the filter, an LFO on the amp and some automation on the velocity of each note. It might sound amazing on its own but leaves very little space for anything else and ends up becoming distracting from your groove. Each to their own, but I personally much prefer a repetitive groove with slight variations e.g. subtle filters and automation over time, than a load of mad modulation going on.

Also, I think of my production process like I’m in a band; maybe this is more relevant to the style of music I make, but if you can’t get your idea across with five simple instruments e.g. a drummer, bassist, lead guitarist, rhythm guitarist and singer then the idea’s probably not very good.

What helps you stay disciplined when you’re tempted to overdesign a sound, especially in a synth that is so complex?

As I mentioned, I think experience teaches restraint. A lot of the most memorable house records (and the oldies that people still play today) usually have the simplest arrangement and sound design but both are perfect for the situation. So now, before I get stuck into any sound design or modulation, I’ll ask myself if the sound already works as it is. I’m more concerned about musicality than making crazy, complicated sounds.

If I’ve spent ages tweaking a patch and getting nowhere, I’ll bounce it to audio, commit to it and move on to another part. I can always come back and edit the audio later if needed, but getting stuck twizzling knobs for hours can send you down a rabbit hole and frankly waste your time.

I often then find when I come back to that part it’ll either work as it is or I’ll be inspired to re-write it to fit whatever else I’ve added. You can also just drop the same midi into a few different patches and A/B test to see which sits better in your mix.

Has your sound design specifically made an impact on your career? As in, how much of your success do you think is attributed to your sound design and selection alone?

Hmm that’s a good question… being honest, I think I’d attribute my success more to my musical background and sound selection than my sound design. I like to think I have good taste which in turn means I pick the right sounds when I produce (and play music that resonates when I DJ) and my approach to sound design is usually a bit more subtle.

Patience is a key element people overlook, for example holding instruments or sounds back so they have a bigger impact when they’re eventually used. On my latest release “Dust” the bass doesn’t kick in until after the first drop (around 2 minutes in the Extended Mix) and it’s way more effective as a result.

As I mentioned, I focus my use of sound design towards musicality such as creating grooves, interesting arrangements, tweaking chord progressions and creating catchy melodies rather than showing off technical prowess, let’s just say there are a lot of happy accidents in my music.

Would you mind sharing one trick you use in Massive to give movement without cluttering the patch?

I like to use Performer on very low rate settings (maybe synced to 1/4) and mapped to the wavetable position or filter cutoff. If you design a performer shape with only 2-3 steps, maybe with a small dip or rise, then dial it back to 10/15% modulation depth it gives the sound a little push, which adds movement but isn’t too obvious.

I also use the macro controls a lot. I’ll map parameters (like wavetable position, feedback or some of the filter options) to one macro and then automate that over a few bars. That way I’m adding variation but the sound feels cohesive. It keeps the patch sounding “whole” while introducing a bit of movement and evolution over time, handy for long builds plus keeping pads interesting and less static sounding.

What’s a common mistake you see newer producers making when it comes to synth programming?

With a lot of beginners what’s noticeable is the lack of movement and progression to a synth, this is usually down to a lack of knowledge of A.) arrangement and general composition and B.) when to use which type of automation.

Composition wise, someone more experienced might tease a lead melody in an opening section of a track, drop the full melody in the middle section then evolve that melody and the patch itself after a second drop whereas a beginner will often add the same synth line three times with little change throughout. In terms of automation, you’ll either hear little to nothing OR all the effects at their disposal set to extreme parameter settings.

I mentioned it before, but less really is more. If it’s used right, a well selected sine-wave with some subtle automation can hit just as hard as a 4-oscillator, modulated bad boy with a shit-tonne of effects stacked up!

Wrapping it all up

Thanks to Jim Rider for sharing how he keeps things in check inside one of the most complex synths out there. His approach is a reminder that sound design doesn’t have to be flashy to be effective – it just has to serve the track. In his case, Massive becomes a tool for feel, not for flexing.

For producers looking to get more out of their synth work without getting buried in modulation maps, this interview is a clinic in editing, commitment, and taste.