Sound design is the art of shaping audio towards a desired goal. That goal may be to create the proper bass synth for a house track or to create the sound of an alien world for a film. The applications are endless and sound designers work in the worlds of music production, film/television, gaming, UX, and more.

Typically, the process of sound design begins with identifying the sounds needed for a given project. Sound designers will either create a sound that exists in their imagination or recreate a sound that inspires them. Regardless of the approach, every sound designer should understand the elements of sound and the tools needed to manipulate them. Below, we’ll dive into the workflow of creating a sound from scratch and provide examples of what sound designers do in different industries.

Watch the sound design basics 101 video below to learn more.

Free sound design plug-ins to get you started: Download KOMPLETE START

If you’re interested in sound design, we’ve put together a free sound design plug-in bundle to get you started. KOMPLETE START has over 2,000 studio-quality sounds you can download for free. It comes with 16 pro-grade synths, sampled instruments, plus effects, loops, and samples to start designing sound.

How to make a sound

Making any sound begins with an understanding of the elements that create the sound itself. Once you understand the different elements of a sound, it’s a matter of understanding the tools you can use to manipulate them. When deconstructing a sound, you’ll need to:

- Choose the right sound design tools

- Identify the timbre

- Shape the amplitude envelope

- Add modulation

- Add effects

1. Choose the right sound design tool

One of the first questions you should ask yourself is, “What audio source can I use to create this sound?” Was the sound created with a synthesizer, a sampler, physical instrument, or field recording? It’s good to familiarize yourself with different types of sound design because you’ll develop a sense for what each tool can do and which tool is right for the job at hand. Here are some common audio sources sound designers use to create sound:

Samplers

Sampling is the process of taking a portion of a sound recording and reusing it as an instrument or sound in a different recording. Samplers allow you to upload any audio file and manipulate it to your liking. For example, you can take the sound of a washing machine, drop it into a sampler, and play it as an instrument in your music. Alternatively, you can record the sound of rain and use it in a podcast to enhance the narrative. While you can go through the process of recording your own sounds, you can also purchase sample packs online or use free resources like freesound.org for faster results. You can find samples for almost anything you can imagine: rain, birds, debris, explosions, as well as physical instruments like pianos, strings, and drums.

Synthesizers

Another way to create sound is by using a synthesizer. Synthesizers are great for creating electronic sounds from scratch. Instead of using live recordings as a source of sound like samplers do, synthesizers use oscillators that generate electrical audio signals. You can then combine waveforms and alter their attributes to create the timbre you want. There are different types of synthesis you should get familiar with:

- Subtractive synthesis

- Wavetable synthesis

- FM synthesis

- Granular synthesis

- Sample-based synthesis

- Additive synthesis

- Physical modeling

- Spectral synthesis

2. Identify the timbre

Now that you’ve chosen the tool you’ll use to create sound, the next step is to choose the waveform(s) you’ll tweak and edit to get to your end goal. What sound will you use as your starting point? Try choosing something with a similar timbre (tonal quality) to the sound you want to create. Once you have your waveform, you’ll tweak and edit until you’re happy with the results.

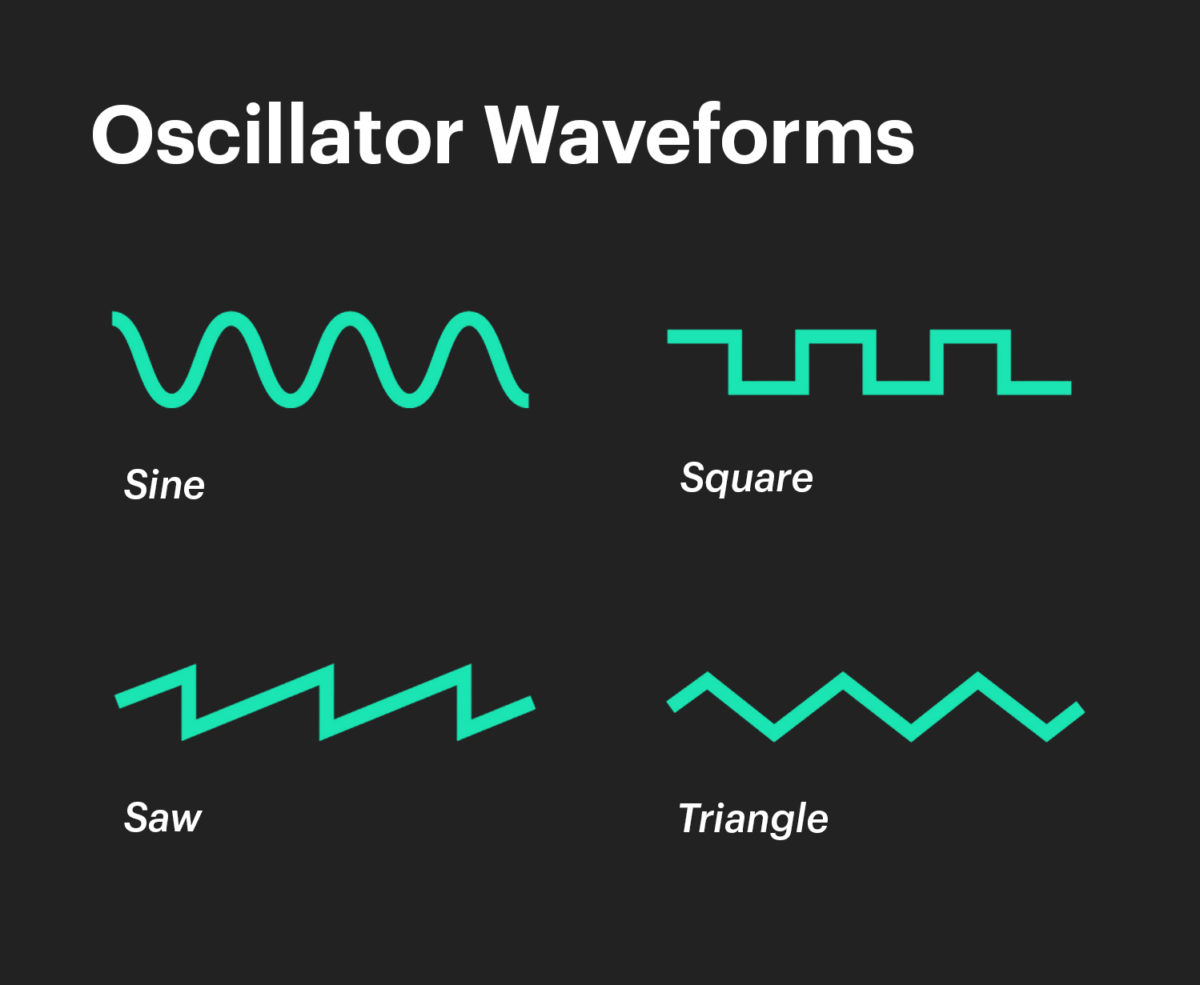

Identifying the timbre of synthesized sounds

If you’re recreating a synth sound then you’ll need to get familiar with the timbre of basic waveforms: sine, square, sawtooth, and triangle. Each waveform has a unique sound. Once you memorize how each of these sounds, you’ll be able to identify these waveforms by ear.

Identifying the timbre of complex sounds

How would you go about recreating a complex waveform, such as the sound of a portal gun? Sounds like these require multiple layers and your approach would require finding sounds that match the timbre of each layer. Essentially, you’re finding the individual pieces of a puzzle: “which sound will give me the sizzle I need? What about the body and punch?”

Here are several approaches to deconstructing the timbre of a complex sound. These exercises can help you identify the waveforms you’ll need to get started designing your sound.

- Loop the sound and write down a list of words that come to mind. These words can be anything as long as they remind you of what you’re hearing. For a portal gun, you may hear a soft kick drum, a flamethrower, a laser, and a computer booting up.

- Where does each sound fit?

- Identify the layer responsible for the attack or transient of a sound. This is the initial impact of the sound, so maybe you’ll use the soft kick drum and laser to fill this role.

- Identify the sustaining layer responsible for the tone of the sound. The sustaining layer is the overall body of the sound. For this, you’ll maybe use the computer boot-up sound as the main timbre of your portal gun.

- Identify the layer responsible for the release of the sound. How does the sound fade into silence? For the tail of your portal gun, maybe you’ll use a flamethrower with a tremolo effect as you automate the volume to silence.

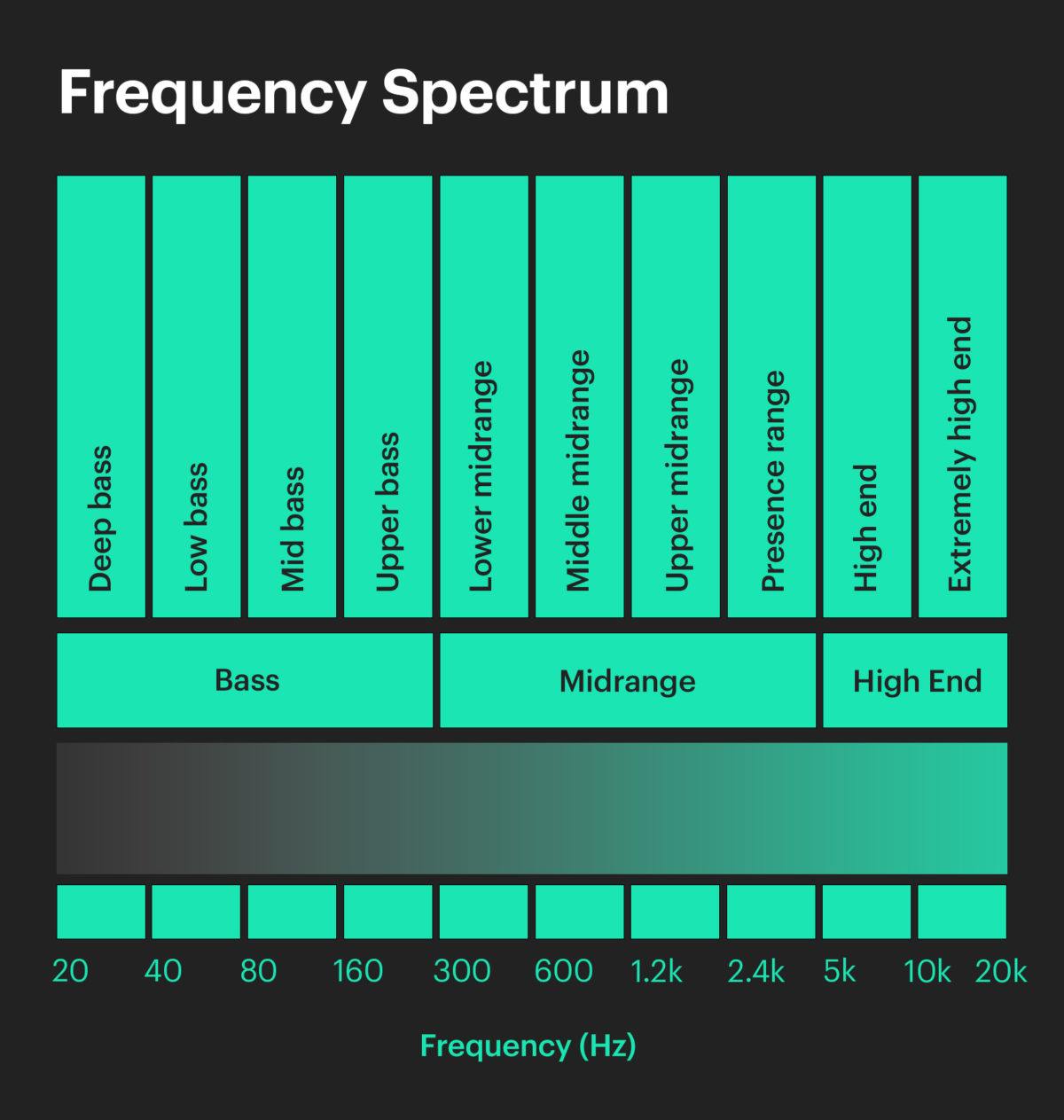

- If you need to put the sound under a magnifying glass, try analyzing different frequency bands of the waveform. What energy is present in the low end, midrange, and high end frequency bands? Try using an EQ to isolate different frequencies to get an idea of how to approach creating your sound.

3. Shape the amplitude envelope

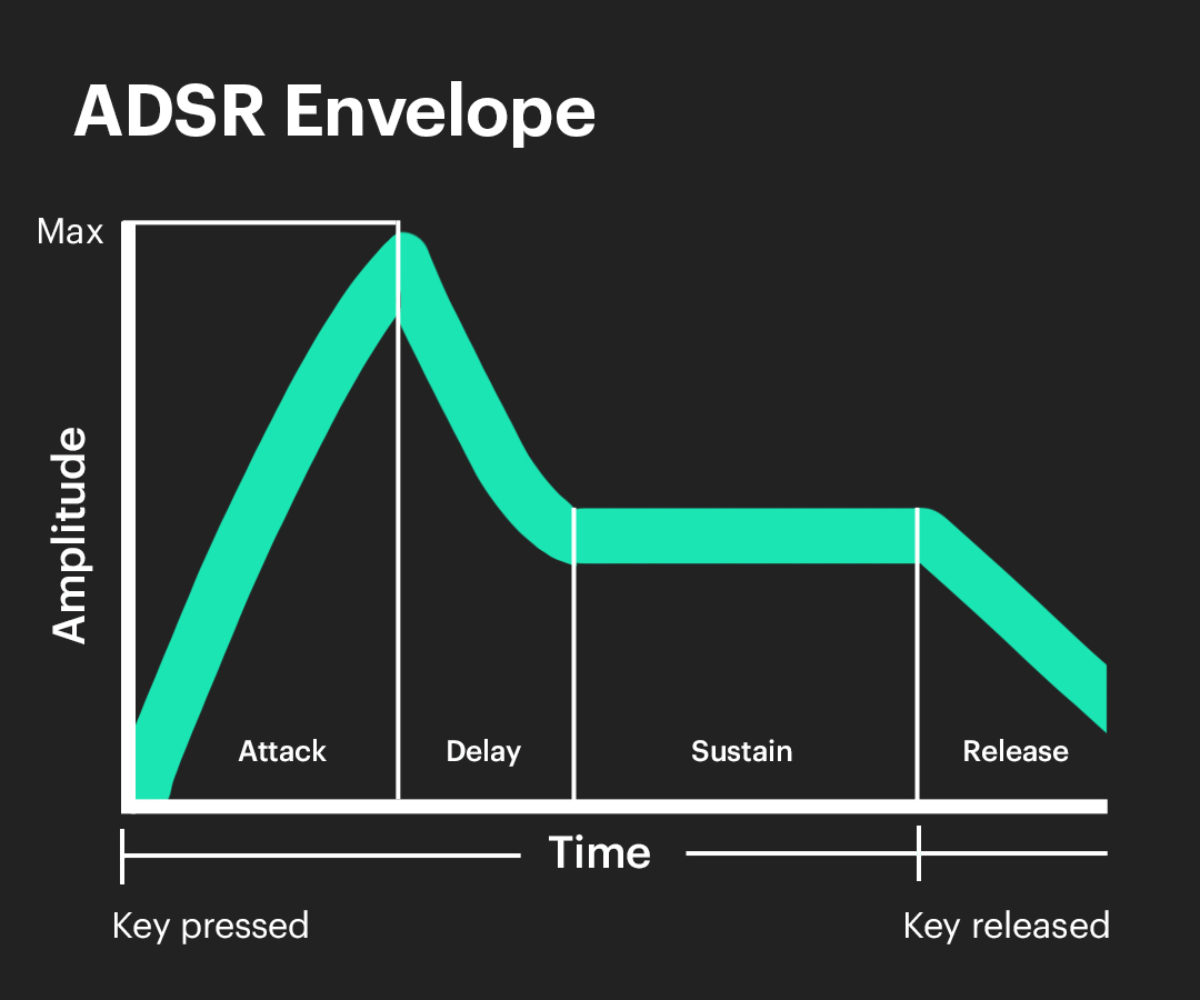

The next step is to shape the amplitude envelope of your sound. Amplitude envelope refers to how the volume of a sound wave changes over time. Does the sound slowly build up or is the impact immediate? How long does it last? Does it end abruptly or does it gradually fade away? The amplitude envelope of a sound can be described by four attributes: attack, decay, sustain, and release

- Attack: the attack time of a sound refers to the amount of time it takes for the amplitude of a sound to reach its maximum level.

- Decay: The decay of a sound refers to the time it takes for a sound to fall from its peak amplitude to the sustain level.

- Sustain: The sustain level refers to the level that a sound maintains as you hold a note. Note: Sustain refers to level whereas attack, decay, and release refer to a length of time.

- Release: the release time of a sound refers to the amount of time it takes for a note to decay from the sustain level to complete silence after a key is released.

Sound designers shape the amplitude envelope of a sound by using the ADSR (attack, decay, sustain, release) envelope built into a synthesizer or sampler or by automating an audio signal’s level in a DAW. So when you’re imagining or recreating a sound, begin by identifying how its volume changes over time and tweak the ADSR envelope of your sound to match what you’re hearing.

4. Apply modulation

Sound is not a static phenomenon, it moves and evolves. In sound design we use a term called modulation to refer to the process of varying one or more properties of a waveform over time. Modulation can help add movement and depth to your sound. When recreating a sound, you’ll have to listen for modulation and apply those changes to your own sound. Some common elements of sound that are commonly modulated are:

- Pitch

- Amplitude

- Frequency content

Once you pin-point the elements that change over time, listen to how they change. Is it a one-time change, is it continuous, or is it random? You can alter a sound by adjusting a knob or slider that controls a parameter like pitch, filter cutoff, or anything else. You can do this by hand, or alternatively, you can assign a modulator to adjust a knob for you.

There are a few different modulation sources you can use depending on how you want to control the way a sound changes over time:

- LFO: an LFO (low-frequency oscillator) is ideal if you want to modulate a parameter in a repeatable and predictable way. An LFO will modulate a parameter continuously. You simply assign the LFO to affect the parameter of your choosing: select the rate at which modulation happens, the waveform which determines the type of motion applied to the parameter, and the amount which sets the intensity of modulation.

-

- ADSR envelopes: envelopes are ideal if you want a change to occur only once after you hit a key. An envelope will adjust a knob according to how you set the attack, decay, sustain, and release.

- DAW automation lane: another option is to create an automation lane in your DAW. Similar to LFOs and ADSR envelopes, the automation lane will modulate a parameter of your choosing except you have to draw the shape of the modulation envelope yourself.

5. Add audio effects

Audio effects are hardware or software processors used to manipulate an audio signal. Understanding audio effects requires a bit of experience because you’ll have to learn how to build a signal chain and how each effect shapes your sound to get an idea of whether a particular effect will help you achieve the sound you want. One of the primary use cases of audio effects is to recreate psychoacoustic phenomena. For example, if you want to create the illusion of space and depth, then you’ll add reverb and echo. If you want to recreate a telephone vocal effect, then you’ll use a high pass filter and maybe some saturation. Some of the main types of effects you’ll use are:

- Modulation effects: chorus, tremolo, phaser, and auto-pan

- Time-based effects: delay, reverb, and echo

- Dynamic effects: compression and distortion

- Filters: Low-pass filters, high-pass filters, and band-pass filters

What do sound designers do?

Sound designers create, edit, and collect sounds for music, film, applications, video games, and other types of interactive media. Their tasks may involve recording, mixing, sampling, building effect chains, sound editing, and sometimes composing underscores.

Learning the art of sound design can expand your creative possibilities and prepare you to work on different types of projects. Let’s explore some of the different roles sound designers play in various industries.

Sound design in film

Sound design is how filmmakers create the sonic world of a film. It plays a key role in creating an immersive experience that manipulates the audience’s expectations and brings the film’s overall atmosphere to life. Some of the main components of sound design in film include creating sound effects, mixing, foley, dialogue editing, and music.

Examples

- Star Wars lightsaber: a combination of the hum of an aged film projector and the buzz captured from microphone feedback near an old television’s picture tube.

- Fighting scenes: cracking walnuts to create the sound of broken bones, smacking slabs of meat to recreate the sound of punches

Brief history of sound design in film

Technology improved over the years and Hollywood began to dominate the world of entertainment. Audiences were for the first time able to experience vast, dreamy landscapes and dazzling special effects through the screen, accompanied by soundtracks that had to match them in scale and splendor. Traditional atmospheric effects, Foley, and other sound design elements were carried over from radio to the fledging film and TV industries before being thrust to new heights, as visuals and sound could be combined in an unprecedented, full-sensory experience.

Filmmakers were inspired by the fresh sounds and radical, boundary-pushing ideas coming out of the music studios of the ‘60s and ‘70s, and many classic landmarks of cinema are celebrated for their inventive and effective uses of sound design. In Star Wars, released in 1977, much of the texture and excitement of the outer-space worlds come from what we hear. The film was the first to introduce booming sub-bass frequencies, which have since come to be expected from any action movie shown in a cinema. The now-instantly recognizable buzz of lightsabers was created by accident, when a sound designer for the film walked in front of an old TV set with a live microphone and some static noise was picked up. Chewbacca’s endearing growls were a mix of real recordings of walruses and other animals. Darth Vader’s notorious breathing noise was inspired by a scuba apparatus. Add to this all the other explosions, lasers, spacecraft engines, and other futuristic noises; without the sound design elements, you’d be left with only half a movie, as half the story is told through sound.

Apocalypse Now, the 1979 Vietnam War epic, opens with a forest of palm trees exploding into flames as helicopters fly past in the foreground. The ‘wop-wop-wop’ sound of the helicopter blades was actually played on a synthesizer, which establishes an eerie, dreamlike atmosphere right from the start. The film was the first to use surround sound in cinema, and the frantic effect of the helicopters zooming across three-dimensional space, around six different audio channels and speaker placements, was the perfect demonstration of what sound mixing could achieve. As the Doors’ “The End” comes to a haunting crescendo, the image of the burning forest is superimposed with a ceiling fan in the protagonist’s hotel room. The synthesized helicopter noises and the sound of the fan are likewise blended, highlighting for us the protagonist’s subjective point of view, his memories of war, perhaps his trauma. It’s a masterful example of storytelling using sound, which even bagged sound designer, Walter Murch, the Oscar that year for Best Sound. In fact, it was Murch who popularized the term Sound Designer as a professional job title in the industry, with a specific focus on creative, post-production sound design.

There are countless great uses of sound design in film, some more recent examples being the bone-rattling drones throughout Inception and other Christopher Nolan blockbusters, or the mechanical whirr of morphing machines in Transformers, almost like a dubstep bass line. These are iconic movie sounds, and they play a huge part in the experience and the success of these famous titles. We already have a sense of the interrelationship between sound effects and the musical score, and how the line between musical and non-musical sound is rather hazy. Further technological advances in the last few decades have drawn these disciplines closer together, as creators have increasingly more processing power and sonic possibilities at their fingertips in a standard home-studio set-up. Software samplers such as KONTAKT and BATTERY are great platforms for importing and manipulating recordings from the real world, as well as accessing enormous libraries of sampled sounds, from percussion and orchestras to electronics from another dimension.

Sound design in music

Generally a music producer might use sound to compliment an artist’s lyrics, build anticipation in the arrangement, enhance instrumentation, or create a sonic palette that sparks the listener’s imagination. Sound design in music can encompass mixing, mastering, synthesis, sampling, and other experimental recording techniques.

Examples

- Transition effects in electronic music: genres like EDM use a combination of mixing techniques and synthesizers to create pitch risers and noise sweeps that build anticipation for a drop.

- Robotic vocal effects: vocoders, exaggerated pitch correction settings, chorus, reverb, and delay effects are used to create robotic sounding vocal effects popular in modern pop music.

Sound design in video games

Sound design in video games incorporates a combination of techniques used in film, UX, and music. Sound designers have to create sounds for menu screens as well as the sound for entire digital worlds that come alive with audio.

Sound design in UX

UX refers to the quality of a user’s experience with a product or service. When it comes to designing a user’s interaction with a product, the main goal is to minimize friction, confusion, and frustration when completing tasks. Sound design in UX is important because it can help:

- Provide feedback of a user action or system status

- Amplify visual elements

- Draw attention to important information

- Establish brand identity

Examples

- Jaguar I-PACE: the silence of electric vehicle motors presents a public health risk to pedestrians who rely on sound to alert them of nearby vehicles. Quiet motors are also unpleasant to the driver who prefers to hear the motor reacting to the gas pedal. To solve this problem, Jaguar worked with sound designer Richard Devine to create the Stop/Start noise of the motors, the audible vehicle alert systems, and the dynamic driving sounds from scratch.

Start designing sound

While sound design may sound like a complicated process, it’s really only a matter of understanding the elements of sound and the tools you need to manipulate them. We hope this guide gave you a helpful breakdown of how to approach your own sound design practice and the different industries you can apply these skills in. If you haven’t yet, get the free download of KOMPLETE START for access to samples, synthesizers, and loops that will help you get started.