Music arrangement is the art of organizing and adapting a piece of music. It involves making decisions about how different musical elements such as melody, harmony, rhythm, and instrumentation are structured, orchestrated, and presented within a composition.

The main elements or components that comprise the arrangement are form, instrumentation, rhythm, harmony, and possibly sound design and textural elements. In this article, we will explore the different possibilities of arranging techniques, the aspects of arranging music, and how those aspects can impact the way the music is perceived in a particular production.

Jump to the basics of music arrangement:

- Form

- Instrumentation

- Rhythm

- Harmony

- Sound design and textures

- Putting it all together in a real-world production

Get started arranging your music with the tools included in Komplete Start, a free bundle of professional-grade instruments, samples, synths, and more.

1. Form: how the different pieces work together

The form of the music arrangement considers how the different parts of a song or musical piece are organized in time. We might have the basic ideas for a song, with a verse, chorus, and a bridge, and then, while in the arranging phase, decide that we want to, for example, repeat the choruses twice and then add a new verse after the bridge. Perhaps that newly added verse will be in the way of a “breakdown,” which then will make us think of how we are presenting that section in terms of instrumentation and dynamics, in contrast to the sections before and after.

I personally find that the decisions that concern the form of a piece are as important as the instrumentation and even the main core elements of a song. We could have a really catchy and memorable melody with some great lyrics, but if the parts are not well thought-out and we have the wrong amount of repeats or not enough sections to keep the attention fresh, then we might end up with a not-as-engaging music piece.

If the form is well put together, the music should feel exciting and new to the degree that we are presented with something familiar (therefore comfortable and enjoyable – “feels like home”), yet surprising enough to keep the listener always excited about the new things that are coming as the song develops.

Let’s take Queen’s masterpiece “Bohemian Rhapsody” as an example

A lot of us are familiar with this 1975 classic by Queen. Although it is not their only long-form and multi-section song, it is certainly their most famous.

This is an example of a masterfully crafted piece that takes you on a whole journey, but only after setting the tone and inviting you into a very familiar musical universe for almost three minutes. This is why I am using it as an example for exploring form. And as we will see here, Freddie Mercury’s influence from classical music is especially present in this song.

After the iconic vocal intro and once the piano comes in with the arpeggiated motif, the song seems to settle into a pace, and it more or less develops as a traditional pop song, with a verse followed by a chorus and then another verse and chorus (although the lyrics do not repeat as we would expect in a typical chorus). Then, at approximately 2:36, Bryan May comes in with an incredible guitar solo over the same chord changes we had been familiarized with for a while.

So far, things have happened in a more or less expected way. Then, after almost 3 minutes into the song, things change drastically: a sudden change of key takes us into a completely different musical section, which develops and moves through various variations, ultimately turning into the epic rock song we know, with chants, new heavy guitar riffs, and even more guitar solos.

This is a really clever manipulation of form. By introducing this completely new section, the song gets refreshed in a way that is completely unexpected, and by doing so, the return to the original motif and tone of the song at the end makes for a full-circle-type reward. By moving further and further from what we once knew as our musical home during the first 3 minutes of music, coming back to the original key and mood at the end is a much-awaited gratification. This is the type of song that will make you want to take a few moments to reflect and process what just happened once it’s done.

Without getting too technical or scholastic, it is worth pointing out that the way the return to the opening theme happens is very similar to the way a classical concerto is structured. We could think of the guitar solo that begins at 4:45 and then merges into a piano run at 4:52, acting similarly to what a cadenza would do in a concerto. Usually, that would happen at the end of the “development” section (similar to how the brand-new and more adventurous section happens here starting at 3:00) and would be a time for the soloist to flourish and play an almost improvisatory solo section. After that, the return to the original theme and key would take place.

If you are curious about this and want to explore it in more depth, I would recommend you research the “Sonata Form.”

2. Instrumentation: who is playing what?

When we talk about instrumentation, we are referring to the choice of sounds or instruments that will take the different musical roles in the arrangement. We can take the same musical parts that are played, let’s say, with a guitar, a single voice, and a fiddle in a folk song, and re-assign them to a synthesizer (to play the chords), a cello to take on the vocal melody and, perhaps, a banjo (to play the melodic bits from the original violin).

Even without changing a single note in the arrangement, by modifying the instrumentation, we will certainly impact how the music is perceived. Changing the instrumentation is changing the textures that we hear, and that is one of the most powerful ways to shape the sound of an arrangement.

In this case, we are talking about changing instrument by instrument for parts that were already crafted. This could be quite effective when working with a piece of music that has an arrangement that is easily recognizable, and by changing the instrumentation only, we will catch the attention of the listener by playing the same notes but with completely different timbers.

In a very different scenario, where maybe there is no previous music arrangement when we choose the instrumentation, we are setting up a bunch of parameters to what will be possible. For me, it usually starts with a melodic idea (or a chord voicing idea) and thinking about what instrument would be cool to use for it. But the other way, where I think of an interesting sound regardless of the notes, can trigger all sorts of musical brainstorming, just based on the possibilities of the instrument and what we have heard that instrument play in other songs or works.

In more traditional settings, we could think of various types of pre-set ensembles we could use as a starting point for possible instrumentations in a project. A few of these could be a string quartet (two violins, one viola, and one cello), a jazz combo/rhythm section (piano and/or guitar, upright bass, and drums), a big band (basically a jazz rhythm section plus a horn section comprised of four trumpets, four trombones, two alto saxes, two tenor saxes, and a baritone sax).

Other standard instrumentation types found in traditional music are an SATB (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) vocal ensemble or choir (a choir will have multiple singers of each) and chamber and full symphony orchestras.

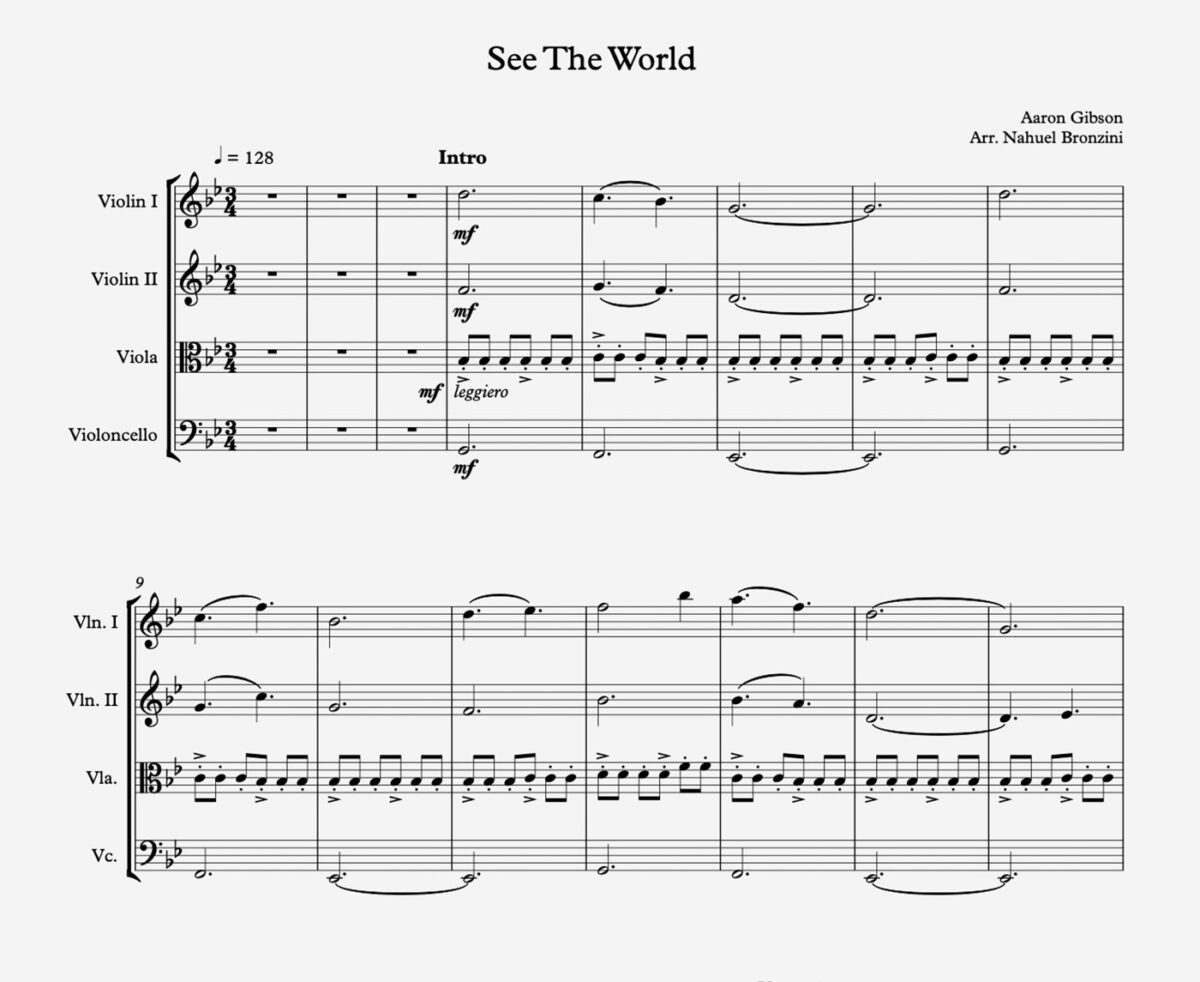

“See The World” by Aaron Gibson – arranged for Electric Bass, String Quartet and Voice

This is one of the most special projects I’ve been involved with, both because of the sensibility of the music and the technical challenge to craft an arrangement for it. Here, the choice of arranging instruments and how each part fit the musical puzzle was critical to making it all work together.

The main challenge here is that the electric bass plays over a wide range of textures and notes, from the lowest part of the register with deep notes filling the space to more percussive and higher-up registers.

A string quartet typically has very distinct ranges and roles for each one of the instruments. Cello usually takes the lowest part of the spectrum, violins covering the highs, and the viola ties it all together in the center.

In this case, the quartet takes different shapes and roles as the song progresses to either imitate some of the sounds the bass is creating or become an element of contrast and create a fuller sound by covering whatever the bass leaves open.

For example, during the intro, the bass provides a rhythmic strumming pattern over where the voice is singing, and to complement that, the quartet is playing long, sustained chords with some melodic accents to support the vocal. This creates a rich and balanced sound during that section. The spacing of the notes and how wide open the quartet is playing is key in order to create both support and space for the bass to poke through and the vocal to still be the primary focus.

3. Rhythm: groove and beyond

Often overlooked, rhythm is one of the key components of arranging. From the time we add a new melodic component or modify a song’s melody, we are making rhythmic modifications to the piece. If we take the notes of an existing melody and change the length or starting point of some of the notes, the melody will feel quite different from the original. This would be a simple rhythmic change to the arrangement, but it can have a huge impact on how the music is felt.

Once we have a change of rhythm in the melody, that will prompt other parts that are playing off of the melody to change (this could be an accompaniment part playing chords under the melody), and when we change the accent of the chord changes in a song, then we are changing how the groove feels. All the musical pieces are connected and feed off of one another. It’s fascinating. We just need to listen closely and see how things impact other elements in the music once we make a change.

Let’s listen to “1612” by Vulfpeck as an example

This would be a completely fine song that could work perfectly even with an evenly played guitar strumming pattern or half notes playing the chords down on a piano. It has a set of harmonic changes similar to a standard blues I-IV type situation, and that’s great all on its own. But the way the different parts are arranged rhythmically really takes the song to the next level.

The syncopated bass and drum kick create all sorts of accents, while the piano’s ostinato helps to keep time. Those two elements together give a sense of groove. The “groove” is all that interplays together, the hits and the spaces in between. This allows for the vocal to do all sorts of playful twists to the melody. By having a very distinct rhythmic feel, there’s a lot of room for improvisation and spontaneity. This song is really all about groove and having a good time.

4. Harmony: the soul’s musical substance

This is a personal favorite for me. Chords are sort of the pathways to pull someone’s heartstrings. There is so much we can do with a simple chord substitution or a subtle inversion of one of the existing chords in a song.

Many times, when working with songwriters, my job as a producer and arranger is to find what is already working in the music and what could use a small tweak in order to elevate the core elements of a song. I find that the chord changes and how these are arranged throughout the song is one of the key factors for a song to work. I usually lean towards small, subtle changes rather than big re-harmonizations of sections. But sometimes, a song might just not have enough harmonic motion and start to feel too repetitive or not engaging enough after a few repeats of a simple chord progression.

If we get lucky, we may find ways to make the existing melody work over a different set of chord changes. This could give the chorus section of a song a whole new perspective, or even a bridge that stands out could be created with this approach.

Pat Metheny’s guitar arrangement of “Don’t Know Why”

This is a beautiful example of what can be achieved by reimagining the supporting chord changes to a song.

If you are familiar with this song, which was made famous by Norah Jones in her debut album “Come Away With Me,” you will hear how cleverly Pat Metheny kept the original melody almost intact while giving it an entirely new meaning with his reharmonizations. What I love about this version is that he makes sure we are well accustomed to the song during the first section of the arrangement, playing the melody as we know it and only subtly altering how the harmony underneath works, with minor variations and changes in range, adding and subtracting bass notes, but without any significant alterations to the chord structure.

Then, once we think that will be about all we get, he introduces some really clever and tasteful chromaticism to the part and takes the chords way far beyond their original key, starting at 2:04. But this all works and feels natural because the melody’s structure is kept intact. By holding from the familiar, he is able to take us on a complete harmonic journey.

5. Sound design and textures: using soundscapes in music

As part of music arranging, in modern music production, we have the ability to add textural sounds that are not necessarily hinting at specific notes or chords but rather can create a halo of sound around other elements, adding a sense of space, a certain color tint, and vibe. A good example of this is adding vinyl crackles and noise in the background or ambient sounds from the real world (it could be city soundscapes, the sounds of birds chirping, or the sound of crashing waves at a shore).

We hear examples of this as early as The Beatles and Pink Floyd. In this way, sound design elements become almost part of the instrumentation decisions, and the way we utilize these sounds can affect how the different parts of the song feel.

If we have a certain background sound playing during the intro but then we make it fade out when the vocals come in at the verse, then we are making formal decisions in regards to this texture. The texture might stay during the whole song and suddenly be removed at some point to create a sense of contrast.

Truly, there are no written rules about how we use textures or really anything. (Perhaps there are some rules written out there, but I highly encourage you to use your ear and your own taste. If it feels good, then that means it’s working!)

A look at texture: “Wish You Were Gay” by Billie Eilish

This is one of my favorite songs from Billie’s debut album. What a great addition to contemporary pop music. Both in terms of sound/mixing and production/arrangement.

Everything is done with subtlety and wit. So is the use of sound design in this song. Billie and producer Finneas used what sounds like field recordings of crowds to comment on what the lyrics are describing and also to generate textural transitions between sections. Here, the use of sound design is both a sonic and lyrical addition. To find these bits, use headphones and go to 0:12, 0:29, 1:35, and 2:47 (this one is really subtle).

6. Putting it all together in a real-world production

Here is an example from a recent production I did for Chilean artist ZAPLA, in which we used a hybrid approach to the arranging and production process, having instruments that played in a more improvisatory way and others that were more scripted.

The song was presented to me as an acoustic piece with just guitar and a vocal. In the produced version we can hear a main acoustic guitar, which carries the original seed of the song, and then the rest of the elements (piano, upright bass, electric guitar, drums, cellos) were arranged and added to complement the initial idea.

Guitars, piano, and upright bass were played following a chord sheet and with some instruction provided during the recording sessions, but without an explicit written-out part. The cello parts were first composed playing on a DAW with a MIDI controller using Kontakt’s Session Strings 2 and later made into sheet music for a cellist to re-record them at a studio.

Having a realistic string sample library was crucial for finding sonic inspiration to craft a part that would speak to the song and blend well with the already recorded acoustic instruments.

Here is a snippet of the track with the VST strings as they were used during pre-production corresponding to the final section of the song that starts at 3:08. Some elements are muted during the first couple of measures so we can hear the cello parts more clearly in this example.

Start arranging your music

I hope by now you are ready to dive deeper into the world of producing music with an arranger’s mindset. It’s all about thinking holistically about the music you are working on and remembering that there are no set rules for how to approach a project. Although we broke down the main aspects that comprise an arrangement, in all of these examples, there was more than one aspect involved in the process.

The musical landscape is vast, and we can go deep on a variety of topics and specific disciplines. If there is something we discussed in this article that sounds particularly interesting to you, go ahead and dive deeper. Having a strong foundational understanding of functional harmony, orchestration, and the different qualities of different instruments, or a good understanding of synthesis, are all tools that will enrich your perspective and give you the space to create even more freely.

Think of music making, arranging, and producing like cooking or making a salad, where any and all of the ingredients will impact the final result of the meal. Taste, crunchiness, and amount of spice are all connected and working together to create an amazing experience.

I encourage you to experiment and use the tools we have to craft unique combinations of sounds and textures that speak to you. Don’t mind painting outside the lines. It’s all part of the process. Take a melody, try it on a synth, change the instrument to a different sound, double it, pan it, filter it. Have fun with it. Find out what moves you. I am sure that will speak to others too.

Kontakt has an amazing palette of sounds and possibilities a few clicks away for you to try out all sorts of sonic possibilities, and the free Kontakt Player is included in Komplete Start for you to get started.