As far as electronic musicians go, Chicago-based producer Kavain Space lucked out with a pretty strong birth name. But Space eventually came to be known as RP Boo — short for Record Player Boo — as he became one of the early originators of the footwork genre during the 1990s.

Though a local legend, Space was relatively unknown outside of Chicago until 2013, when a pair of archival releases (Legacy and Fingers, Bank Pads & Shoe Prints) solidified his presence in the culture at large. Legacy was released on Planet Mu, the label run by Mike Paradinas. Space was also a peer and collaborator to the late DJ Rashad, and is considered by many to be the godfather of Chicago’s essential footwork sound. Since these releases, the producer has spent much of the past five years touring the world, sharing his quixotic style with the rest of the planet.

Native Instruments spoke with Space about the evolution of his tools, and his career’s overlapping arc with the sound of the city.

How has your life changed in the past five or so years, since your music started to become recognized more widely?

Me being in the city of Chicago, I was able to pay attention to what different producers were doing — especially when ghetto house came up — and I could hear things and take them and make tracks. It was so super easy, with all type of ideas.

But then, as I started travelling, it changed. At that time I had just gotten an MPC Studio, and I’d take that with me and come up with a track while I was out. I could actually put it down, right there where I stood; that let me know that I didn’t have to be in Chicago to make this happen. I was able to take what I see, no matter where I go, and say, “Hey — this is a moment, something on my mind. Let me put this down right now.”

When you are back home in the studio, how has your gear and setup changed over the years?

Well, I still have my Roland R-70, but I haven’t produced a track with it in years. Used to be: plug it in, turn it on, create the beat right here. That was it. But now we have all this software and technology. Now, with technology, I can go back and add something, or take something away based on how I feel — that’s the most beautiful part, that I couldn’t do with the R-70. Create something different, after doing the original.

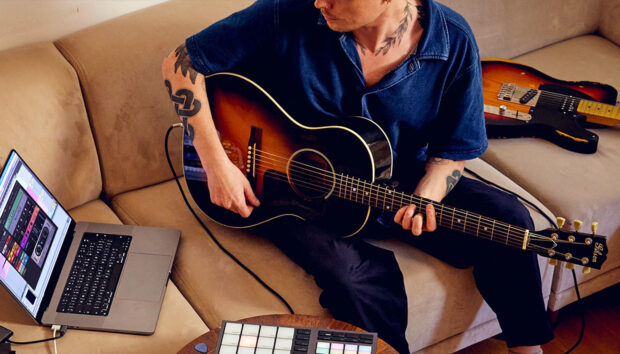

These days I have a variety of gear to work with, such as the Roland TR-8, Akai MPC Studio, Ableton Push 2, Akai MPK 225, Ableton Live, and Native Instruments Komplete Kontrol.

What inspires me now is that I have much more selective gear that’s within my reach to choose from. I know they all have a different choice of sounds and [workflow] approaches, and that gives me more room to explore and be creative. Back some years ago, I was limited with the drum machine and just made the best of it. Back then, the gear I used was obviously limited; now there’s so much “room” that you can realize you won’t be able to finish a track. It can come a time that you feel it’s complete, and then another sound or sequence comes to mind, and there you go — back to adding something.

That said, even though I haven’t used the R-70 in years, I know it’ll still be of use if I decide to go back to it.

How do you work? Do you wait for inspiration, or just sit down and get into things to get the creative juices flowing?

Something I learned back in the day is that a lot of producers would rush themselves. I learned how not to rush, and how to only do something as a project if I feel like I have the time to do it — if I have some “space” to take it on. It becomes a challenge, rather than a question of, “I’m bored.” I don’t like to sit still, but that would challenge me to the point where I could do something that I really wanted to do, but not make it feel like something from the past. Now, if I don’t have anything on my mind, I just go about my day.

When I work on a new track, I just go with how I feel — it’s never forced, and if there’s nothing on my mind to create, I just don’t open up at all to start a track. I’m very self-motivated,

Through your eyes, how did footwork develop and come to life? How did the city of Chicago inform your musical output?

The city planted a seed, yes. I love what music has done for many — even before I was born and started to produce. It was the love of playing tunes with and for the people that motivated me to keep producing. The sound of footwork was developed from people in Chicago just gathering at parties, doing different dance moves with each other, and being complemented by local DJs; over time, it just came into existence with full force with social meaning.

Footwork is known for its creative and off-kilter approach to rhythm and syncopation. How did you approach beat construction in a way that felt different to what others were doing at the time?

A lot of people, especially if they start with the bass, it’ll end up guaranteed to be on the one. I learned how — but I didn’t know it until my father explained it to me, years later — to unravel a small mystery in electronic music. When the metronomes came out, you knew where the one was. But before that, it was hard to catch; not too many people know how to do that. I have plenty of tracks that people think are on the one, because I know how to play them and make them fit on the one — but they’re not on the one. I got tracks that are on the three. I learned that by watching DJs, even if I didn’t know the lingo.

You talked earlier about the newer tools allowing for more revision and alteration, after the initial idea has been put down. How do you know when a track is done, particularly these days?

If I feel that it’s finished, it’s done. But I’ve “finished” tracks in the past, and then been listening to that track in my headphones afterwards and gotten new ideas to go back and add.

The longest it ever took me to do a track was called “Last Night” — did that one years ago. Took me almost nine months just to say I was ready to record it. There was too much traffic coming in and out the house, too much having fun, some of the buddies come over ; I don’t like to work with people in the house, and time would pass. But I eventually got it done.

Lastly, how’d you get the name RP Boo?

My brother gave me that name. He was aware of what was happening at the time — CDs were more popular, and vinyl was declining, and he’d noticed that everything had switched over to CDs. I was still playing vinyl, though. I came home one day, and he said, “What is a DJ?” I said, “Disc jockey.” And he said, “What does CD stand for?” I said, “Compact Disc.” Then he pointed to the turntable, and said, “What do we call it?” I said, “Record player.” He said, “You’re the only one playing records, so that’s your new name — Record Player Boo.” And I loved it. Never looked back.

Photo credits: Deandre Nobles