Songwriting is an ancient art, effectively as old as human culture itself. Over the years and generations, familiar formats and customs emerge in the structuring of songs—whether following intuitive folk traditions or more formalized rules dictated by music theory.

The mathematical patterns that make up songs are mostly subconscious to us as we listen. That said, we can definitely notice when the balance is right and the music just ‘works’. In fact, the secret to successful songwriting often lies in finding a perfect balance between fulfilling and subverting the listener’s expectations. We can identify basic song structures that are shared across a broad range of artists, genres, and eras of popular music.

This article will break down the component parts of a song and introduce the most common arrangement shapes, analyzing some song structure examples from popular music along the way.

Jump to these sections:

What is song structure?

A song structure refers to the arrangement or organization of the different sections of a song, such as the verse, pre-chorus, chorus, bridge, and other parts. It is the blueprint that dictates how the song progresses, and it helps give the song its shape and flow.

The structure of a song is the shape of the story it tells—its narrative arc from beginning to end.

Song structure becomes second nature to the listener, but thinking in terms of these shapes will help you to work more efficiently and write more effective and powerful music.

Without an organized structure, your song is just an abstract scramble of musical ideas and themes. Of course, this can be desirable in more freeform, experimental music. But pop song arrangements tend to be ordered and formulaic, and this sense of familiarity is precisely what makes them catchy and appealing to a wide audience.

Let’s run through the main sections that make up a song. These are the building blocks of musical arrangement, but bear in mind that there are always exceptions to any rule—many popular songs mix up their own blend of sections and conventions, and what ‘works’ in any instance will depend on the unique ideas and style of the song itself.

Basic structure of a song

The basic structure of a song includes the intro, verse, pre-chorus, chorus, bridge, and an outro. These can be placed in different sections of the song or repeated depending on the type of song you are writing. We’ll get into more detail about each of these elements below.

Intro

It’s important to catch the listener’s attention and draw them in at the start of a song. This can be with a big, explosive statement, or by easing into the groove more subtly.

A more technical function of the intro is to establish the tone, tempo, and instrumentation that follows. The length of the intro can vary widely, from a quick lead-in to a full, extended section—live performances often feature longer intros to set the mood and build the audience’s anticipation.

Many songs open with the main hook or motif played solo, while in the case of EDM tracks the intro is usually a drum beat.

Verse

Songs generally feature multiple verse sections, which make up the bulk of the runtime.

This is where the main storytelling occurs—each verse contains lyrics that develop a narrative in a linear progression over the course of the song.

While the lyrics are usually (though not always) unique to each verse, they tend to follow a similar melody and rhyme scheme each time, and stick to a consistent length—typically 16 or 32 bars.

Chorus/Refrain

The word ‘chorus’ literally means bigger, fuller, with more voices. The chorus is the climax of a song, its big statement (both lyrically and musically).

In contrast to verse sections, the chorus features the same lyrics each time it repeats—hence it is also referred to as a ‘refrain’. This repetition gives it an anthemic quality, pulling the sections of the song together into an overall unity.

A major decision in songwriting is the balance between the verses and chorus. In some cases they are musically similar, e.g. the same chords continuing throughout the song. Other examples feature a more drastic contrast and opposition between sections.

Pre-chorus/Post-chorus

These sections are optional and don’t feature in every song. That said, they are commonly used to maintain a smooth flow between sections, build up tension for the big release of the chorus, or work as a harmonic pivot into a new chord progression.

An effective use of pre-chorus sections can be heard in Lana Del Rey’s hit “Video Games”—the music sustains on the dominant chord for a moment of pause (at 0:58, 2:24, and 3:23), before the vocal descends five steps in the line “tell you all the time”, into the resolution of the chorus.

Bridge/Break

A bridge section is typically used only once, usually heard just before the final chorus. It introduces variation, with new chords or melodic material to keep things interesting late-on in the song.

A ‘break’ or ‘breakdown’ is an equivalent section that originated in jazz and soul music and was then adopted in hip-hop and electronic dance tracks. This refers to a section of reduced instrumentation, literally a break from the main musical material. A solo might feature here too.

Outro

The ending of a song sometimes mirrors the intro, or there may be a unique section to tie things up in conclusion. On the other hand, some songs end with an abrupt stop, especially in more aggressive rock or punk styles (e.g. “Song 2” by Blur).

Gradually slowing down at the end of a song is called ‘ritardando’, a word taken from classical music. Alternatively, many songs slowly fade out to silence. Such techniques help tail off a song’s intensity and make it easier to blend in the context of a DJ set or album.

Common song structures

1. Verse-chorus

This is the basic song structure that we hear most often in contemporary popular music. A narrative unfolds across multiple verses, intercut with a repeating chorus that states the song’s main theme(s). Most songs feature two or three verse-chorus cycles.

Depending on the song, one of these binary parts is given more weight and power, while the other serves as background support. Pop hits are usually centered around a big, climactic chorus, while songs with more of a storytelling focus, such as folk, rap, or musicals, will place more emphasis on the progression of the verses and use a chorus to break things up.

Let’s take a look at Miley Cyrus’s new single, “Flowers,” an instant ear worm which has broken numerous sales and streaming records in its first weeks since release.

The structure of the song is ABABB. More precisely, we could subdivide the chorus sections into chorus + post-chorus (the line “I can love me better” has its own independent melody and rhythm, but it follows the chorus each time consistently).

The song doesn’t do anything groundbreaking—it follows the same chord pattern throughout and taps into our familiarity with traditional song structures. But it’s perfectly balanced and manages to sound simultaneously classic and current. A lot of this is thanks to its shape—verse, chorus, verse, chorus, repeat the final chorus, and we’re done. Magic.

2. Verse-chorus-bridge-chorus

This is another widely used template in popular music. Following on from the basic verse-chorus structure, a bridge adds another layer of sophistication and variety.

A textbook example is “Since U Been Gone” by Kelly Clarkson. The song has the structure ABABCB, and each section can be easily distinguished with its own tone, melody, and chords. The bridge section contrasts with the rest of the song and occurs only once, followed by a final chorus refrain.

“Angels” by Robbie Williams demonstrates a different approach. Here, the bridge is an instrumental break featuring a guitar solo, while the chords and overall mood match the chorus sections.

In contrast again, the bridge in “1979” by The Smashing Pumpkins is the most intense part of the whole song. When it hits (at 2:30), it seems to lift off from the chorus and deliver a full, euphoric release, whereas the rest of the song is relatively restrained.

3. 32-bar form

This is an earlier song form that peaked in popularity in the first half of the 20th century, but it established the trend for the modern structures detailed above.

These songs are split into four sections of eight bars, structured AABA—two verses, a contrasting B section, and closing with a final verse. The term ‘middle eight’, used in modern parlance to refer to the bridge, comes from this style of song.

The 32-bar form was a popular shape for show tunes. The definitive example is “Over the Rainbow,” sung by Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz (you can hear the song shift into the B section at 1:16).

To explain this trend for short, snappy song structures, we have to consider the time limitations of early recorded music using vinyl. Time brought improvements in technology that allowed songwriters the freedom to compose more extended arrangements, but the 32-bar template has stuck around.

Individual sections often adopt the AABA shape within longer, more complex songs—“Yesterday” by The Beatles is a good example of a more modern extension of this structure.

4. AAA

Certain types of song, including hymns, ballads, carols, and nursery rhymes, are comprised of just one repeating section, through which a story develops.

We also find this in the traditions of country and folk music. “Scarborough Fair” by Simon and Garfunkel is built from one verse section, but the intensity gradually grows as more complex vocal harmonies and instrumentation are added each time we hear the repeating sequence.

Songs with a verse-verse-verse structure can still be split up with a refrain, but this isn’t distinct enough to be a separate musical section. In “Jolene” by Dolly Parton, the song follows the same chord sequence throughout, and what could be regarded as the chorus is just a short lyrical repetition, literally a refrain.

Dance music is often composed entirely around one repeating musical motif. Check out Laurent Garnier’s classic track “The Man With The Red Face”—the same bass and chord pattern repeats throughout the track, while the rises and falls in energy come from fuller or sparser instrumentation on top.

The same thing features in rap and hip-hop, e.g. “Get A Hold” by A Tribe Called Quest. It’s true that many hip-hop tracks follow a verse-chorus structure, but in this case it could also be regarded as AAA, split up with a refrain but musically the same throughout.

5. 12-bar blues

The twelve-bar cycle follows the chords I, IV, I, V, then back to I, with a predictability that allows a soloist free range to improvise over the top and know what the rhythm section will be doing underneath.

One of the most common chord progressions in 20th-century music, this structure originated in jazz and blues before bleeding into early rock-and-roll hits like “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry or “Shake, Rattle and Roll” by Big Joe Turner.

Another famous example of 12-bar blues is the 1962 instrumental “Green Onions” by Booker T. & the MGs.

6. Through-composed

A core ingredient in songwriting is repetition, but your song need not be cyclical or symmetrical. Take James Blake’s “Retrograde” as an example. Although it is bookended by a similar-sounding intro/outro, the main body of the song follows a linear AB structure—intro, verse, chorus, outro.

Another popular structure is ABABC, where the song breaks from the verse-chorus cycle into a unique bridge section at the end, not looping back to earlier material. Radiohead use this a lot in their songs—for example, “Nude”, “Karma Police”, and “There, There” all follow this structure.

Tips for finding the right song structure

Song structures are more guidelines than strict rules, and most songs feature their own nuances and variations—even the examples used in this article aren’t completely clear-cut.

When working out how to structure a song in your own writing and music production, it ultimately comes down to a lot of experimentation, trial and error, and feeling to get the balance right.

What feels natural?

How much contrast there is between sections is completely up to you and the particular flavor of the song. For example, we’ve touched on the question of where an AAA structure with refrains becomes a separate chorus section—it’s a bit ambiguous.

One motif can make a whole song, so don’t underestimate the importance of the hook. There are countless examples of this, but how about “Smells Like Teen Spirit”—the iconic opening riff makes up the skeleton of the entire song. The only time it deviates from this is in short post-chorus sections to transition back to the verses (at 1:23 and 2:37).

Start structuring your songs

If you’re struggling with a song, there can be a tendency to add too much and overwork an idea until the inspiration is gone. Instead, try a more minimalistic approach—embrace repetition, getting a feel for how subtle fluctuations in the melody or the rhythm can be more impactful than big, bombastic shifts.

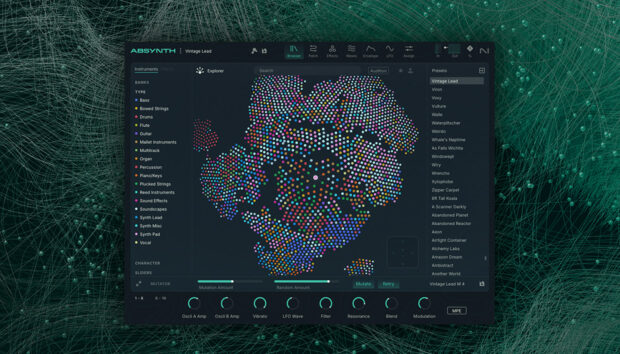

If you’re making your first steps into the world of songwriting and learning about musical structures, KOMPLETE START is a useful, free bundle of sounds and practical tools to practice with.