Music theory is often associated with classical musicians and performers. Because of that, it might not seem like essential knowledge for a producer or beatmaker. Believing this can severely limit your music production skills. Learning music theory empowers you with tools to elevate your craft in significant ways. On top of giving you an efficient workflow, an understanding of music theory will foster creativity and give you deep insight of elements of music like samples, drum beats, chords, and so much more.

If you’re ready to step up your music writing game, then you’re probably wondering how to learn music theory. This article will serve as a guide to get you started, and will point you in the right direction to begin – or continue – your music theory journey. If any particular ideas here grip you, feel free to jump around and click on the hyperlinks throughout the article to learn more.

Jump to these sections:

Follow along with this tutorial using Komplete Start, a free collection of pro sounds, instruments, and more to get you started creating music.

What is music theory?

Music theory is the study of the elements and structures of music. It encompasses a range of concepts – from the very basic, such as understanding how musical notes are written on a staff or piano roll, to more complex ideas like the relationships between chords and scales. Essentially, music theory provides a set of principles for musicians to analyze, compose, and perform music.

Modern Western music theory was built on the musical language that composers have established through their works over the last several hundred years. Theory is based on what already sounds good to our ears and not the other way around. That’s worth mentioning as while music theory serves to create guidelines, there are no hard and fast rules that you absolutely have to follow. Still, having a well-formed grasp of the basics will help immensely when composing your own music.

Can I teach myself music theory?

With such a broad topic at hand, you might think that you need to attend music school to wrap your head around it. While options like music degrees and diplomas are available for some people, unfortunately, that’s not a reality for everyone.

Luckily it is absolutely possible to teach yourself music theory. The availability of online resources, books, and courses makes teaching yourself easier than ever before. Many of these resources are even available for free. Start with basics like definitions and terminology, then gradually progress to more advanced topics like harmony and composition.

You don’t need to lay out a fortune of cash to start learning music theory. What you do have to bring to the table are your curiosity and some discipline. Consistent practice, actively listening to music, and experimenting will solidify what you’ve learned.

Music theory essentials

Let’s get started and look into the basics of music theory. The topics below are all interrelated, so understanding one concept will likely impact how you view the others.

Please be aware that all of the information in this article is based on Western music theory. This is one way of tackling ideas that are prominent in popular music, but there are many other systems of musical knowledge that exist outside of this framework.

Rhythm

The term “rhythm” covers timing aspects of music – meaning the patterns of notes and silences that fill up time. A few important topics that may fall into the rhythm category are beat, tempo, polyrhythms, and syncopation.

Beat

In the music production world, we sometimes refer to the instrumental part of a track as a “beat,” but that’s a bit of a misnomer for the theory side of things. A beat is the most basic unit of time in music. It’s the steady, underlying pulse that you feel when you listen to a song. The beat provides a solid framework for organizing musical events and serves as the current that pushes the music forward. The prevalent beat in a song is dictated by a “time signature” that looks like a fraction. Two common time signatures are 4/4 and 6/8.

Tempo

Tempo is the speed of a musical piece. The tempo sets a song’s overall pace, and can also influence the mood. Slow tempos usually result in a reflective atmosphere, while faster tempos can create energy and excitement. Tempo is described in “beats per minute” or BPM for short. Faster BPMs are used commonly in energetic dance genres like drum and bass, or trance, while lower tempos can be used for chilled genres like lo-fi, and ambient.

(Note that in a DAW you can usually find the tempo and time signature controls together near the transport window.)

Polyrhythms

Polyrhythms happen when we simultaneously play multiple rhythms on top of each other. Experimenting with polyrhythms can add complexity to your music if you use them cleverly. Polyrhythms are popular in dubstep, jazz, and many kinds of non-Western music.

Listen to this example of polyrhythms found in the Spotlight Collection: West Africa sample pack for Kontakt.

Syncopation

Syncopation occurs when the emphasis in a musical passage is placed on offbeats. It’s a technique that adds a sense of unpredictability and groove to the rhythm.

Melody in music

You’ve probably had an earworm before – when a song gets stuck in your head and you can’t shake it off. If you have, then it is most likely the melody that has ended up being that earworm. The melody of a song is the part that you can sing or hum, and it’s usually the most prominent part of a track. A melody is a linear succession of musical tones that forms a recognizable musical phrase.

Melodies are characterized by their pitch, rhythm, and contour. They are also called “top-lines” and in the context of pop music are often performed by the vocalist as the front-and-center element of a track.

Pitch

When we talk about how high or low a note is in music, we are talking specifically about pitch. A note’s pitch is based on its fundamental frequency. The higher or lower that fundamental frequency, the higher or lower the pitch.

Each pitch in music has a unique name based on where it is located on the piano roll. We refer to a pitch firstly by its letter name, and secondly by a number that corresponds with the octave of that particular pitch. All pitches will contain one of the following letter names:

A, B, C, D, E, F, or G.

As well as a number ranging from 0-8.

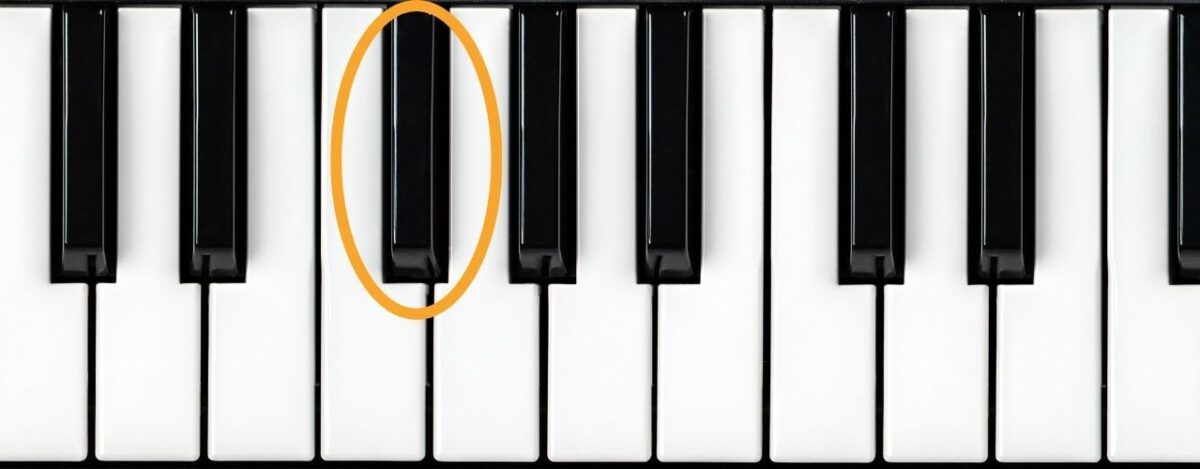

A pitch description might also include something called an “accidental.” The two accidentals are “sharps” (#) and “flats” (b). A sharp means that a note is immediately above the letter-name description, and a flat means that the note is immediately below the letter-name description. An Eb is directly below a natural E, and a C# is directly above a natural C.

This low–pitched note is A#1:

And this high–pitched note is D5:

Sometimes accidentals can share a place on the keyboard/piano roll. For example, F# shares a place with Gb. We name them differently for analytical reasons, so don’t get too hung up on this technicality when learning the basics of music theory.

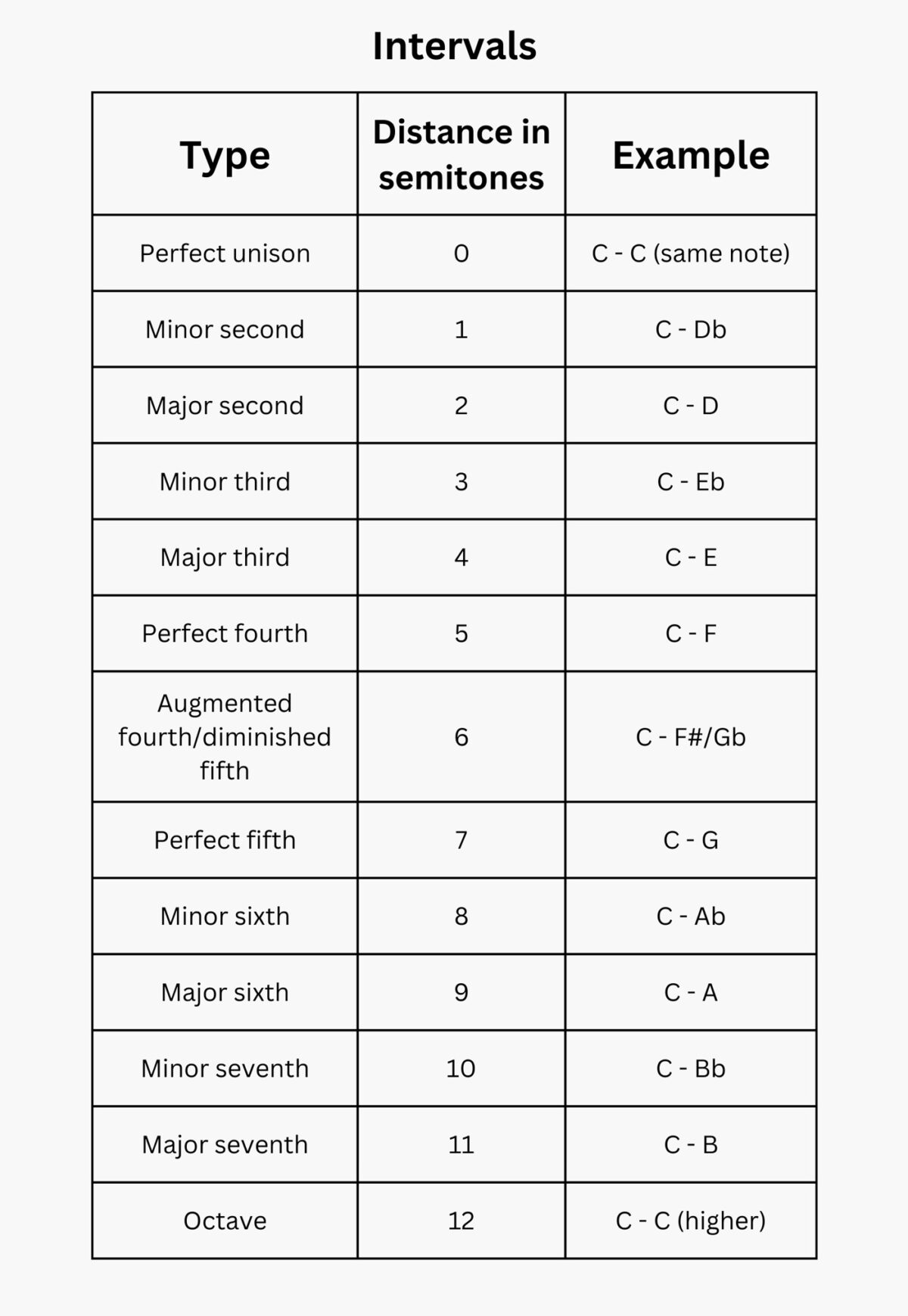

Intervals

An interval is the difference in space between two different pitches. There are several ways to categorize intervals. We define intervals with the following terms:

1. Type

This refers to the quality of the interval, and how large the space is between two notes. There are five types of intervals: major, minor, perfect, augmented, and diminished.

2. Distance in semitones

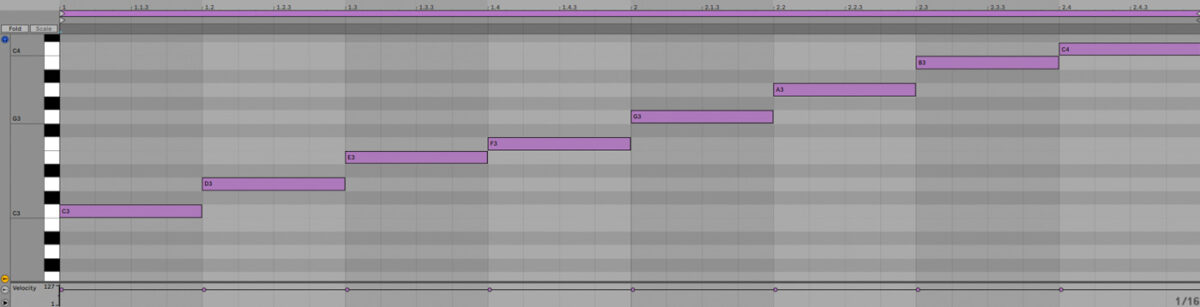

A semitone is the smallest distance between two notes in Western music theory. For instance, D and D# are one semitone away from each other. The distance two semitones away is called a whole-tone, or simply a tone. E is one tone away from D.

3. Distance in letter names/numbers

The difference between notes’ letter names determines which numerical value we assign to the interval. Let’s look at this in practice:

We can see that the distance between C and E is three notes (including C, it is C, D, and then E). Therefore we call this interval a third. This particular example is a major third as it is also four semitones away. If the E was flattened to Eb, and was three semitones away, it would be a minor third.

With these concepts in mind, you can refer to this table to explain what kind of interval exists between two pitches:

When intervals are played in succession they are called “melodic intervals.” When they are played at the same time they are “harmonic intervals,” and result in harmony and chords.

Harmony in music

While melody may be the most easily recognizable part of a song, harmony is an essential underlying element that gives the melody its emotional context. Harmony imbues music with tension as it navigates further from a tonal center, and releases as it arrives “home.”

Harmony occurs when stacking several notes on top of each other simultaneously. Harmonic intervals can transform a solo melody:

Into a harmonized melody:

Or create chords.

Chords in music

A chord is a group of three or more notes that are sounded simultaneously. Chords are fundamental building blocks of music theory and play a central role in the structure and character of musical compositions.

We name chords based on which intervals are present. The lowest note in the chord usually determines the letter name of the chord. Following that, the third and fifth intervals are defining features. If there is a major third present (measured from the root note), it is a major chord. If there is a minor third present, it is a minor chord. The same goes for the fifth interval which determines if the chord is diminished or augmented.

If we look at an E major chord, it contains the notes E, G#, and B. The E – G# interval is a major third, so it is a major chord. The E – B interval is a perfect fifth, which we don’t need to specify in the chord name.

Triads

Chords with three notes like E major are called triads and generally consist of a root note, a third, and a fifth. These kinds of chords are widespread in popular music. You get the following kinds of triads:

1. Major triads (root note, major third, perfect fifth)

2. Minor triads (root note, minor third, perfect fifth)

3. Diminished triads (root note, minor third, diminished fifth)

4. Augmented triads (root note, major third, augmented fifth)

Chord extensions

Moving beyond basic triads, chords can actually feature any scale note. When we add notes to a chord over and above the triad we are adding “chord extensions.” This can result in wonderful and unique chord sounds that can be heard in a myriad of genres like jazz, soul, and house.

Let’s take the E major triad from earlier and add a D# and an F# on top of it. Those notes are both in the E major scale, which you’ll read about later.

Now it is called an E major 9. It is called a “9” rather than a “2” because we are extending the chord above the initial octave or “8.” E major 9 sounds like this:

Extending chords will add vibrant color to your compositions.

Chord inversions

An inversion is simply when you change the order of the notes in the chord that you’re playing, and place something other than the root note in the bass voicing. Let’s look at the same E major triad from before. It consists of E, G#, and B. Those notes, however, don’t need to be played in that order.

If we put the third note at the bottom and play them as G#, E, and B it is called a “first inversion” and it sounds like this:

If we place the fifth note, B, at the bottom of the chord, it is called a “second inversion”, and it sounds like this:

Inverting chords can provide smooth voicing motion when changing chords in the context of a chord progression. It also makes chords sound less stable, so they can be used to provide a small amount of tension relief without fully arriving at the tonal center.

Chord progressions

Chords should weave together to create a sense of build-up, and an eventual release of tension. When we string together a series of different chords, it is referred to as a “chord progression.”

Chord progressions are a vital part of songwriting, and the chord progressions you choose will dictate the mood and structure of your compositions. There are lots of common chord progressions used in certain genres like R&B and pop.

You’ve likely heard this chord progression before:

That is a vi-IV-I-V, and it is an extremely common chord progression in pop music. You can hear it in songs like “Ghost” by Justin Bieber:

As well as “BEBE” by 6ix9ine and Anuel Aa:

The same chord progressions can be used in countless songs without being considered plagiarism. Feel free to include some that you like in your compositions. Just make sure to write your own melodies.

Which chord progression should you use in which contexts? How do people write chord progressions in the first place? In order to understand the answers to these questions, you’ll need to wrap your head around keys.

Keys in music

To keep things sounding consistent and pleasant to our ears, our compositions often employ keys. A key grounds a piece in a “tonal center” and acts as a guide for which scales we should choose for a song’s chords and melodies.

A key will be named as a letter, followed by its quality (usually major or minor). For example, a song could be in the key of A minor, in which case, the piece will be mostly based on the notes of the A minor scale which are A-B-C-D-E-F-G-(A).

This scale will influence the tonality of the piece as most of the melody notes and chord tones will derive from that scale.

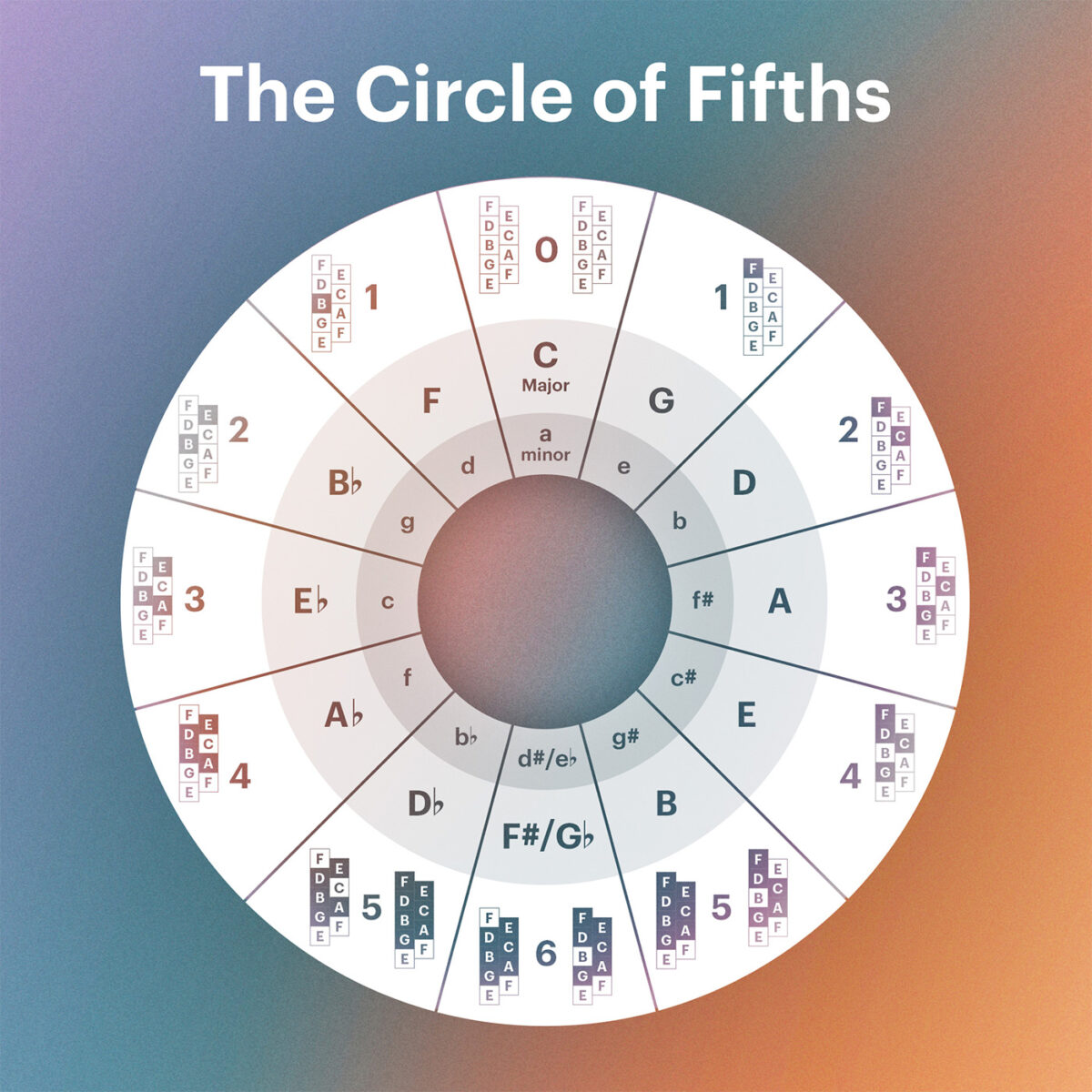

Circle of fifths

The circle of fifths is a valuable tool when working to understand keys and scales. It allows you to visualize keys according to what their scales are made up of and how keys are related to each other.

Moving clockwise around the circle, sharps (#) are added into the key or scale. Moving anti-clockwise, flats (b) are added.

Music scales

If keys are derived from scales, it is important to understand what scales in fact are. A scale is a particular sequence of notes that makes up the material we use to build chords and melodies found in compositions. The most common scales are major and minor standard scales, and they consist of particular interval formulae.

Major scales

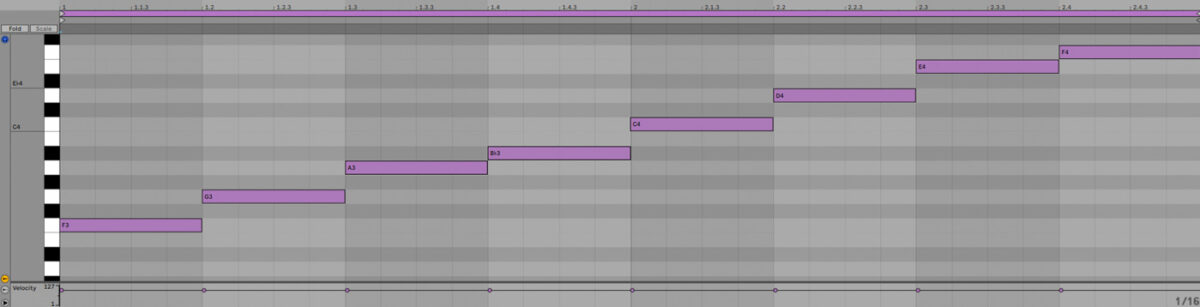

The major scale sounds like this:

And is made up of this formula:

Tone-tone-semitone-tone-tone-tone-semitone.

In the key of F, for instance, that formula will result in this scale:

F-G-A-Bb-C-D-E-(F)

Minor scales

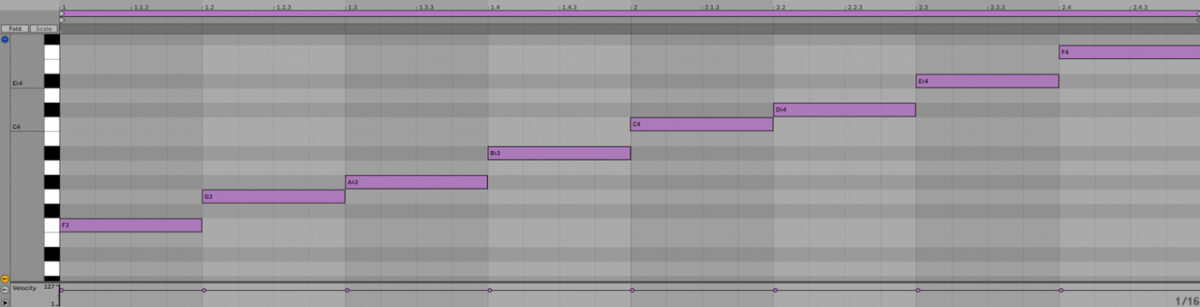

The minor scale sounds like this:

And is made up of this formula:

Tone-semitone-tone-tone-semitone-tone-tone.

The F minor scale will therefore consist of these notes:

F-G-Ab-B-C-Db-Eb-(F)

Take a look at the circle of fifths to see why these keys have flat notes in them.

Music modes

If you understand the concept of scales, getting a grip on modes shouldn’t be of much trouble. Modes are a way of repurposing scale formulae to give new tonalities based on interval relationships. That might sound a bit complex, but it’s actually very simple.

A mode is created by taking a scale and using its exact notes starting from a different scale degree. So let’s take a look at our F major scale again.

F-G-A-Bb-C-D-E-(F)

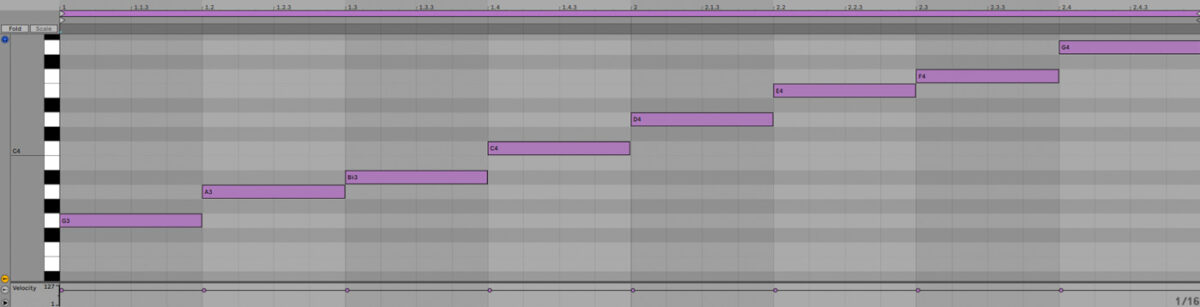

That’s the standard major scale, which – in the context of modes – is also called an Ionian mode. If we take the same notes of that scale but begin on the second degree (G), we are left with a new mode.

G-A-Bb-C-D-E-F-(G)

That is called a Dorian. It is a minor scale that features a raised sixth degree, which gives the tonality a bit of brightness. It sounds like this:

There are seven modes of the major scale, each with its own formula. Modes can be created with other scales too.

Songwriting

In addition to harmony, chords, scales, and everything else we’ve talked about so far, there are other ideas in music theory that could benefit your songwriting approach.

Song structure

Song structure is an element of musical arrangement. Just like with chord progressions, it is common practice to use and re-use established song structures. Structure your song by organizing it into distinct sections like verses, choruses, and bridges.

We can refer to parts of our songs as letter names like “A”, “B”, and “C” (don’t confuse these with keys or pitches). Consider experimenting with traditional song structures such as AABA, verse-chorus, or ABAB.

YouTuber 12tone gives a fantastic breakdown of song structure in this video:

Timbre

Timbre is another crucial songwriting concept – it means the texture of the sound in music.

Timbral choices often materialize as instrument choices because particular instruments have unique tonal and textural characteristics. Choosing instruments that fit the mood of your composition is a significant decision that can heavily affect the listener’s perception of what you have created. Let’s look at the same melody played on two different instruments to assess their contrasting emotional impact.

This is a simple melody played on a piano:

Here is the exact same melody played on Massive X, using wavetable synthesis for a different timbre:

Neither of these is necessarily better than the other, but it is up to you as a songwriter to decide what fits your intention more cohesively. Perhaps the instrumentation of the first example would easily fit into a pop song, while the second lends itself to an electronic niche.

Start learning music theory

With a foundational understanding of music theory, you can apply a more informed approach to your own songwriting and beat making. Good theoretical knowledge will help you make decisions rooted in common musical practice.

Learning music theory is one of the best ways to elevate your skills as a composer. And yes, you absolutely can teach it to yourself! Start practicing music theory with Komplete Start, a collection of free music production software.