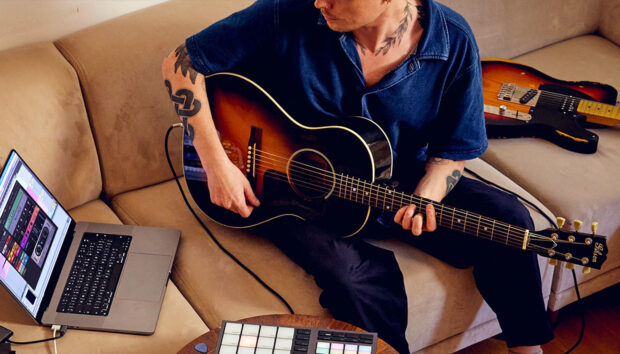

Major Seven, a.k.a. Omar Walker, is a prolific 26-year-old Atlanta producer known for his deft use of soul samples and intricate drum work. In his short career, Walker has already produced for the likes of Future, Rick Ross, and Jay-Z, with a series of collaborations on the way including both big names and up-and-comers. Walker also happens to be a Native Instruments product specialist, and recently got his hands on the new MASCHINE. We talked shop with Walker between his many commitments during the run-up to the A3C music festival and conference in Atlanta.

What’s usually the starting point when you’re working with other artists?

I always ask what kinda vision someone has for their record, and ask them for different music references. I’ll play them a couple of beats with a similar sound, and peep their reaction. Once you can figure out what the direction is, you know where to go.

As far as making the beats, I came up in the digital era, so for me crate digging is going on YouTube [laughs]. I’ll go searching for really rare sounds and really rare music, listening for certain parts that catch my attention. Then I’ll usually go on iTunes and buy the record, just so I have the highest quality; sometimes, though, it might even be better to have that distorted YouTube quality – it depends what the vision is. Either way, I’ll load it up in Maschine, and start doing sample chops.

What’s your process like for that?

First I’ll convert the sample to WAV or AIFF and then load it in Maschine. I’ll set my pads to fixed velocity, because I like to hear everything at the same volume and at the loudest volume while I’m working, and make sure my polyphony is at one, so that all the samples aren’t overlapping each other while I’m playing. There are a lot of options, but I usually don’t use any of the auto-slicing features; I usually manually choose the start and end point of all the samples, and then duplicate until I have all the chops that I want. I really fine-tune those start and end points of all the chops, even though it takes more time.

You’ve been using the MASCHINE STUDIO for that, and recently started using the MASCHINE MK3 as well, correct?

Yeah. That’s my biggest feature on the Mk3 – they added those larger screens, which is what I love about the Studio so much. The screens make it so easy to see what you’re working on, to zoom in with the knobs, and having the different colors for clarity – it makes it an exciting workflow. To have it on a portable Maschine is amazing. I’d always bring my Mk2 with me when I was traveling, because a lot of times I have to work on the road. I preferred my stationary setup at home, but now I can still be as comfortable and effective when chopping my samples on the road – now I basically have a portable Maschine Studio, with all that functionality.

Just having Maschine there as my drum library is great. It’s so organized, and it’s so easy to just choose one sample and then go to your keyboard and that one sample is now an instrument – I can play every sample, I can tune every sample as if it’s a piano. That’s such a key feature to me, because I play melodies with so many percussion and drum sounds. And even with drums, I like to put those in key.

How do you accomplish that?

Well, because you can change the pitch so easily in Maschine, you can click on your sound and then go to your keyboard and find where that C is – so when you press C on your percussion, it’s in-tune with your piano sound. At the same time, you have to go with the song – sometimes what feels better might be something off-key, so you just have to know the rules to know when to break them.

Once you get your chops done, what comes next?

The first thing I’ll do is play around with the chops and try to come up with an arrangement that pretty much everybody could connect with. Once I find that right combination and right timing, I’ll start recording them into the DAW – I use Logic X and Pro Tools – and figure out the perfect tempo. I’ll also select all of the chops and start playing around with the pitch as well, because sometimes having a higher or lower pitch, a faster or slower speed, can change the effectiveness of the record. There’s a lot to think about when you’re producing. I tell people all the time, producing is really just a series of decisions, and you’re trying to make the right decision all the time. Even when you make the wrong decision, you just have to know when you do that and change it to the right one. It’s all about trial and error; the consumer only hears the final product, but it’s all about the process.

How specific are the artist briefs you generally get?

It’s funny, record companies will often send out these “who’s looking” lists, with a bunch of artists that are working on their projects at the time. They’ll have a description of where they want to go with their album, or what kind of songs they’re looking for, and it’ll say things like “uptempo,” “90s feel” – stuff like that. Sometimes you can go based on that, but a lot of times artists also want to experiment and see what you can bring to the table, and hear what you have and see if it inspires them. One thing I’ve learned is that a lot of times those lists are wrong, and the stuff you’re making that you expect an artist to be on, is not the stuff they end up getting on [laughs]. They always choose the stuff you least expect.

How often do those artists come to you with specific ideas or sketches?

There are times when an artist will have an acapella of something they did, and they felt like the production could have been stronger, or they want to go in a different direction with the production. Other times, there are artists I work with that might write to their acoustic guitar; I’ll be able to record the vocal arrangements and the guitar separately, and then I’ll be able to produce the record based on where I think the production can best complement the vocals. The guitar might not end up on the final production, or it might have a completely different amp or effect to where it might not even sound like a guitar anymore.

It’s a very experimental process—sometimes you have to take risks. A good example of a hit would be the “Selfish” record that me, Detail, and Mantra did for Future and Rihanna. Based on the previous work that Future had done, we were worried about being responsible for ruining his career! [laughs] We didn’t even see the vision of him being on that type of ballad, but it turned out to be an amazing record. You have to be open to creativity and not box yourself in.

How much of your life as a producer these days is in the studio with artists, versus making stuff on your own to share with them later?

I think for the most part, nowadays it’s mostly just creating on your own. We’re in such a fast-paced world, where everybody wants things right away; the artist just wants to come to the studio, hear a hit, cut it and be out [laughs]. There’s a lot less of what producing was back in the day, even though it’s still a very useful skillset. I consider myself a well-rounded producer, not simply someone who makes beats or writes songs. You can be the producer just by emailing a track – and that’s cool, but I feel like as a producer you should have other skillsets, so that if you’re working with a musician or instrumentalist or engineer, you can communicate with them. But yeah, nowadays it’s a bit of a lost art, because a lot of artists prefer you to send music or come to the studio and press play… they just want the record.

Have you seen a change in your career from the older way of doing things to what you just described?

Oh, most definitely. The sessions that have best honed my production skills are those that I’ve done with independent artists or upcoming artists, where we really sat there and created the music from scratch, together. It would be more experimenting, and a longer process. But most of the major placements I’ve gotten have been from just submitting the music that I create on my own. You just always want to keep creating; even when you don’t know what you’re gonna be working on, you just have to have a vision of where you see music going.

But like I said, I do love to dig for rare samples that make me feel something, catch that emotion. And a lot of the time, these songs were never popular – they were underdog songs that weren’t hits back in the day. For instance, “The Devil is a Lie” song I did for Rick Ross and Jay-Z – when I found that Gene Williams sample off of “Don’t Let Your Love Fade Away,” there were like 3000 views on it. I just try to find stuff that makes me feel a connection.

Sometimes you might hear a song and do an interpolation, which is what I did with the Future song, “Neva Missa Lost.” That’s actually a flip on the Jodeci song, “My Heart Belongs to You,” which is just like a 90s jam. I wanted to flip that into something that was current. Sometimes I might start with a sample and build on the beat, and then take the sample out at the end.

Any final producing tips?

If I’m producing in Logic, I’ll have a template set up for a multitimbral drum track. So I’ll have 16 Logic tracks, each of which represents a pad on the Maschine. So basically I can mix each sound in Logic as if I have 16 instances of Maschine open – it’s a really great template for multitimbral instrumentation. You then start ideas using note repeat – record all the hi hats and drag that MIDI over, and I have it in Logic. Or sometimes, if I’m making something in Pro Tools – usually I do that for collaborations – when people send me some audio files, I might just dump them into Pro Tools. I’ll go through a bunch of sounds in Maschine that might work on the record, and load them up on all 16 pads; I’ll click on one and either record in Maschine and drag out the audio, or I’ll record it as MIDI inside of Pro Tools and convert it to audio.