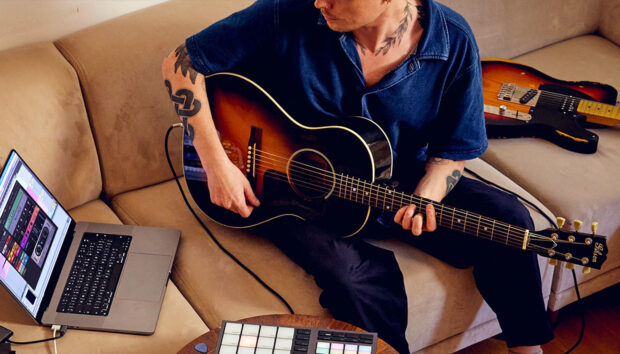

The irresistible elfin waltz of D.R.A.M.’s “Broccoli.” The twisted organ chords that kick off Travis Scott’s “Sicko Mode.” The anthemic pads and horns of Drake’s “Laugh Now Cry Later.” The sultry, jazzy synths of Jessie Reyez’s “Far Away.” What do all these tracks have in common? They’ve all been touched, quite literally, by the hands of producer Rogét Chahayed. At age 32, L.A.-based Chahayed has become rap and R&B’s go-to for clever hooks, unique intros and outros and irresistible synth lines, more often than not crafted with NI’s KONTAKT.

So we thought we’d stop by the producer’s LA studio to find out more about the sounds and processes behind some of his biggest hits. Grab yourself a trio of Rogét’s personal KONTAKT instruments below – a dark piano, a vintage organ, and a Spanish guitar – then read on to learn more about the man himself and get the story behind some of the biggest hits of his career to date.

Note: You’ll need the full version of KONTAKT to load these instruments.

“Kontakt has a lot of really cool libraries that have such realistic samples,” says Chahayed from his home deep in the San Fernando Valley. “Some of my favorite strings to use within Kontakt are Albion and Vivace, which has incredible string runs and sort of orchestral snippets that are really like cinematic, and in some cases almost cartoon-like. I also love Lumina, and Cinematic Strings for the more lush, string-heavy orchestral production. I also use Battery a lot to chop samples that I have made with my analog synths. Having the high-quality sounds and samples is half the work, and the other half is being able to play and arrange correctly. I’ve done a lot of string arrangements via Native Instruments, which later translates perfectly to a real string section playing.”

Rogét didn’t start working with orchestras overnight. In fact, you could say his whole life has been training for this moment. Starting on piano at age 7, he worked his way up to a scholarship at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music – he graduated in 2010 with a degree in Piano Performance, but not before picking up a strong interest in a different sort of composition. “While studying classical piano at college, I sparked up an interest in hip-hop production, especially the stuff that Scott Storch was doing with Dr. Dre,” he recalls. “I was really starting to take more notice of the keys and the sounds behind a lot of those songs and I thought to myself, ‘Hey, I would love to be that guy. I would love to end up stamping my sound into that style of music.’”

“It’s a process that requires patience and a lot of passion,” he explains, of the journey from the classical world to breaking into the rap game. “Basically, I moved back to L.A. and started to integrate myself into the scene a lot – showing up to any studio sessions I could, playing piano on songs, working on ideas, learning how to make beats in Logic.” Eventually he caught the ear of Melvin “Mel-Man” Bradford, one of Dr. Dre’s closest collaborators, who shares production credits on Dre’s 2001 album and Eminem’s The Marshall Mathers LP, among many others. “I sort of became a student of his, and he was a mentor to me,” recalls Chahayed. “He guided me through making beats and then he introduced me to Dre, which in turn led me to having a position at Aftermath as a keyboard player and co-producer. That was in 2014 and that was a very pivotal moment, like ‘Hey, the greatest producer of all time wants you in his presence and wants to share ideas and work with you.’

It was only a couple years from that point until Chahayed hit his other big break: crafting the unmistakable hook of DRAM & Lil Yachty’s “Broccoli,” an addictive, wonky flute loop that resembles a Mozart solo as played by Link from Legend of Zelda. “When we were making ‘Broccoli,’ DRAM was singing this melody and it suggested a flute sound,” he recalls. “I think the combination of the sound that I picked and the way I played it with the right articulation gave it this very Mozart-like element. I think it makes it a little charming, and it’s really cool that something as simple as the way you articulate a simple melody can really give it that specific feeling. Classical music is just in my DNA. Having so much experience playing classical and studying the form and the technique, it definitely bleeds into what I do now.”

Rogét uses a variety of techniques to arrive at his sound, concentrating more on building out layered melodies and less on tweaking each individual sound into something unique. “It’s not necessarily the sound that matters, but how you play it,” he explains. “There’s a quote from a famous pianist named Arthur Rubinstein: ‘There’s no such thing as bad pianos, only bad players.’ It made me think, you know, you can’t blame a sound for being lame. I mean, I’ve used a cheap Casio; I’ve used stock sounds on songs. I do effect things a little bit. If I’m taking a stock Rhodes, I’ll use things like guitar amps or pedals on it or run the sound through plug-ins that makes it sound lo-fi or warbling. Sometimes I manipulate the register, either pitch it up or slow it down a little bit, or add some delay, but I don’t add much. There are a lot of people that like to spend 15 minutes just mixing one thing – I would rather just make it sound good on the fly.”

“Producing is sort of like painting,” Chahayed says, sagely. “You don’t want there to be distracting colors that throw off the whole vibe of the painting. Most times I want to feature the portrait – often, this is the singer – and everything else in the background is there to support that. I mean, there are definitely songs where the riff drives the entire song, like Dre and Snoop’s ‘Still D.R.E’ or Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing.” But usually when you’re working with an artist, you’re trying to highlight their vocal. I think both the challenge and the fun part is making sure that you have enough on the track to where there’s sort of a mattress, you could say, for the melody, for the artist.”

Chahayed’s star only continues to rise – at the moment, he’s working on new tracks with Big Sean, Kehlani, Doja Cat, Olivia O’Brien, and Kali Uchis, along with continued collaborations with Hit-boy. He’s also working with a New Zealand band called Drax Project – whose music is a mix of jazz, hip-hop, R&B and pop – and co-writing and producing with his talented sisters Juliana and Andrea Chahayed. In the meantime, we asked Rogét to tell us about the production of a handful of his biggest collaborations.

Halsey – Bad at Love

Me and the producer Ricky Reed were just having a cook-up session one day back in 2016. He recorded me playing some synth pads on my Prophet 8, which ended up becoming the main loop of “Bad at Love.” After I made that initial synth pad, I slowly started adding a few small elements to it. I pulled up something on Kontakt, I believe it was Synthex, and found a bell-like sound, with which I recorded these high chords – along with the low pad, it created this nice blend of low and high registers. Ricky put the drums on it and then he ended up having a session with Halsey a few months later – she heard the track and instantly gravitated towards it. A song like that is perfect for Halsey because her voice is in the middle register. I think that’s something to take into consideration when you’re making a song or when you’re working with an artist. Does this person have a lower voice? Do they have a higher voice? How does it pierce through the song? “Bad at Love” was more of an atmosphere, but there was enough chordal stuff going on in the bottom and enough high-end things to brighten it a little bit at the top. It was just enough for her to write a legendary song.

Khalid – Vertigo

At the time I was working with a producer named John Hill, who had sessions with Khalid. The rooms were sort of crowded already, so he asked me to send him some ideas from home. I was made aware of the things that he was listening to and inspired by at the time. The main thing I listened for in those references were the chord progressions and the space. Most of the reference songs had two, maybe three chords at most, and I just wanted to give Khalid ideas that had a lot of space for him to float freely on. For “Vertigo,” I pulled up one of my favorite Kontakt instruments, which is the Jazz Guitar factory sample library, and I came up with the initial progression in five minutes. I sent that loop over to John and about a month later, I got a text saying that one loop was going to be a song for Khalid – that main guitar riff that you hear in the song is actually me playing on a small MIDI keyboard. The quality of the guitar sound combined with my knowledge of guitar playing and the intervals being spaced out correctly, really makes it sound like there is a guitarist playing that riff. So I’m really happy with how that turned out.

Nas – Blue Benz

Getting to work on the Nas album was a bucket-list experience for me just as a musician having been a fan of Nas for so long. The Nas album was executive produced by Hit-boy – he called me and said, “There’s a song that we did that I need to really get finished and put the right sound on it.” I was fortunate enough to hear most of the project if not all of it while it was being made; I also co-produced “27 Summers” on that album as well. Although I’m not with some of these artists directly – like with Nas, for instance – I feel like I’m there through the music, and they’re going to hear what I do. So I treat it as if they’re in the room with me. I exclusively used all Kontakt plugins and Native Instruments stuff for “Blue Benz,” in which you hear a lot of strings, piano, driving synth sounds and basses. I really just wanted to evoke a more classic, kind of grungy sound on that song because it’s very reminiscent of New York in the ’90s and the things Nas is inspired by: mob movies, mob figures. I wanted to keep it really sinister-sounding. It was fun to incorporate those sounds and bring the tracks to the finish line with those driving sounds I had put in there.

Joji – Nitrous

Joji is a very special artist. I was introduced to him by 88 Rising, the label and media house that has Joji, Rich Brian, NIKI, a lot of incredible Asian artists. “Nitrous” was a track that I made with Clams Casino, who is a good friend and collaborator of mine; we also made “Can’t Get Over You” for Joji a few years back. Me and Clams created this very different pocket of drums and different chords – weird sounds and things that sound a little off, maybe even a little uncomfortable at times, but I think that’s what makes it natural. The main chord progression that you hear right off the top when you start playing “Nitrous” was created on the fly while we were doing the beatmaking session – I actually used at $40 Casio keyboard that I got from Toys R’ Us and plugged it into some pedals to give it a little more texture.

Big Sean – Guard Your Heart

This song was really special to work on. Pretty much my entire contribution to the album was done with Sean in the room and I also worked directly with Anderson as well, which was a lot of fun. When I started working on “Guard Your Heart,” the basis of the track was there but Hit-boy and Sean were talking about having an intro that was more sort of related to the main piano sample in the song. They just wanted something that would really smoothly transition right into the riff and make it feel like all one solid piece – the word they used was “organic.” The first opening that you hear in the song is a duet with me and Anderson. All the instruments you hear are me playing – the bass, keys, the synth and the strings, which were done with a combination of Kontakt patches. The bass was also from the Factory Library, the Classic Bass sound, which is one of my favorite simple sounds. I ran it through an amp. I put some piano from the Prophet X; I added some synth and strings from my Kontakt plugins, and sort of just created this minute-long intro that kind of makes it sound like an old soul record. That’s when I think Anderson is really good at is bringing soulfulness to the forefront of modern music, but making it current and making it cool.

Travis Scott – Sicko Mode

This was an idea that I created with Hit-boy in 2016 and we didn’t know it was going to be “Sicko Mode.” It started out as a loop in a cook-up session with Hit-boy, probably in the first month of us meeting and working together. It was inspired by the almighty Rapman Waw patch (Hint: it’s in Factory Library > Vintage > Vintage Toys – ed.) – again, in the Kontakt Factory Library, one of my favorite libraries of all time. When I pulled up that sound, it sounded like nothing I’d ever heard – sort of like a cat meow, organ type of thing… I was just blown away.

The first chord I attempted when I pulled that sound up is the first thing you hear in “Sicko Mode.” I went off that sound and added a bass and a few other sprinkles on top and gave it to Hit-boy to check it out – he immediately put the drums on it and we had just kind of looked at each other like “What is this? This is insane!” He made the move to bring it to Travis directly because he has a close relationship with him. And I heard maybe two years later that we’ve got something on Astroworld. I didn’t know much about it.

The first time I heard the song was the night Astroworld came out. I heard the organ… for about 30 seconds you hear my keys and then out of nowhere I heard Drake say “Astro” and I kind of just freaked out. I didn’t even know it was three beats in one song until a few days later. I thought the song was only a minute long and then I realized, no, this is some “Bohemian Rhapsody” type thing where there’s three movements to a song. It reminds me of classical music – a lot of classical pieces have movements: one is medium speed, one is low and the third is fast. So it was very interesting to hear and see people’s response to such a complex arrangement, and they received it pretty well. And I’m like, wow, this freaky crazy organ progression actually became a part of the culture. I saw Travis Scott had his own McDonald’s meal recently and a lot of kids were going up to the drive-thru – when the person would say “What can I get for you?” they would literally play “Sicko Mode” from the top and stop it. This went way deeper than just a song – it’s a part of the culture that won’t be forgotten. And that’s what my aim was to do when I got into this… I want to leave a mark that stays forever.

Last year, we visited Chahayed’s LA studio to learn more about that Sicko Mode organ intro – watch the video here.