Throughout the past few decades, as digital music technology has become more prevalent, there has been a roiling debate about whether older analog music tools are superior to their digital counterparts, or whether new innovations make digital the right path. Certainly there are solid arguments in favor of either side of the debate. Some combatants value the convenience and reliability of digital, while others say that the usability and familiarity of old analog tools is preferable. Naturally, every user’s preference about comfort is too subjective to rely upon, so we can’t get an answer there.

Where the debate really heats up is between analog sound and digital sound. There are some clear differences between analog and digital audio – the differences in the media offer limitations and advantages on both sides. Digital audio has the opportunity to be extremely free from noise or other signal alterations and “imperfections” when compared to analog options. Conversely, analog audio signal can be more flexible with gain, and because of it’s sometimes imperfect nature, sound more pleasing and natural to the human ear. So how do we choose in the analog vs digital sound debate: louder vs cleaner, warmth vs precision, old-school vs future-facing… What if there was a way to choose the best of all the above?

In this article we’ll explore some of the best ways to make your digital mixes sound analog. We’ll look at how audio producers access the good parts of analog signal, and keep the advantages of digital tools as well.

Here are techniques audio producers use to make digital audio sound analog.

1 Saturation and Distortion

In order to get access to the sound of analog, it’s important to look at what analog signals do, and how that differs from digital signal. One of the clearest distinguishing factors between analog sound and digital sound is the how analog signal is changed by its progress across an analog circuit. Any change to the original signal is considered “distortion” – not just when it makes a guitar or synth sound gritty. Distortion can be subtle. It can give a sound that is noticeably thicker and more present. The more gain that’s added to an analog signal, the more change to the original signal (distortion) we’ll hear. This principle is known as saturation – a circuit that is filled up to its limit with signal.

Saturation will often add “warmth” to your sound. This generally refers to a fuller low end, and smoother highs. Another effect of saturation is more rounded transients, with a somewhat gentle compression effect. You may also notice that certain sounds carry further up into the frequency spectrum; this is a result of “harmonic excitement” which we’ll talk about more below. Overall, saturation and distortion will make any of your sounds seem more “present” in the mix – a very handy tool when you’re mixing digital sources.

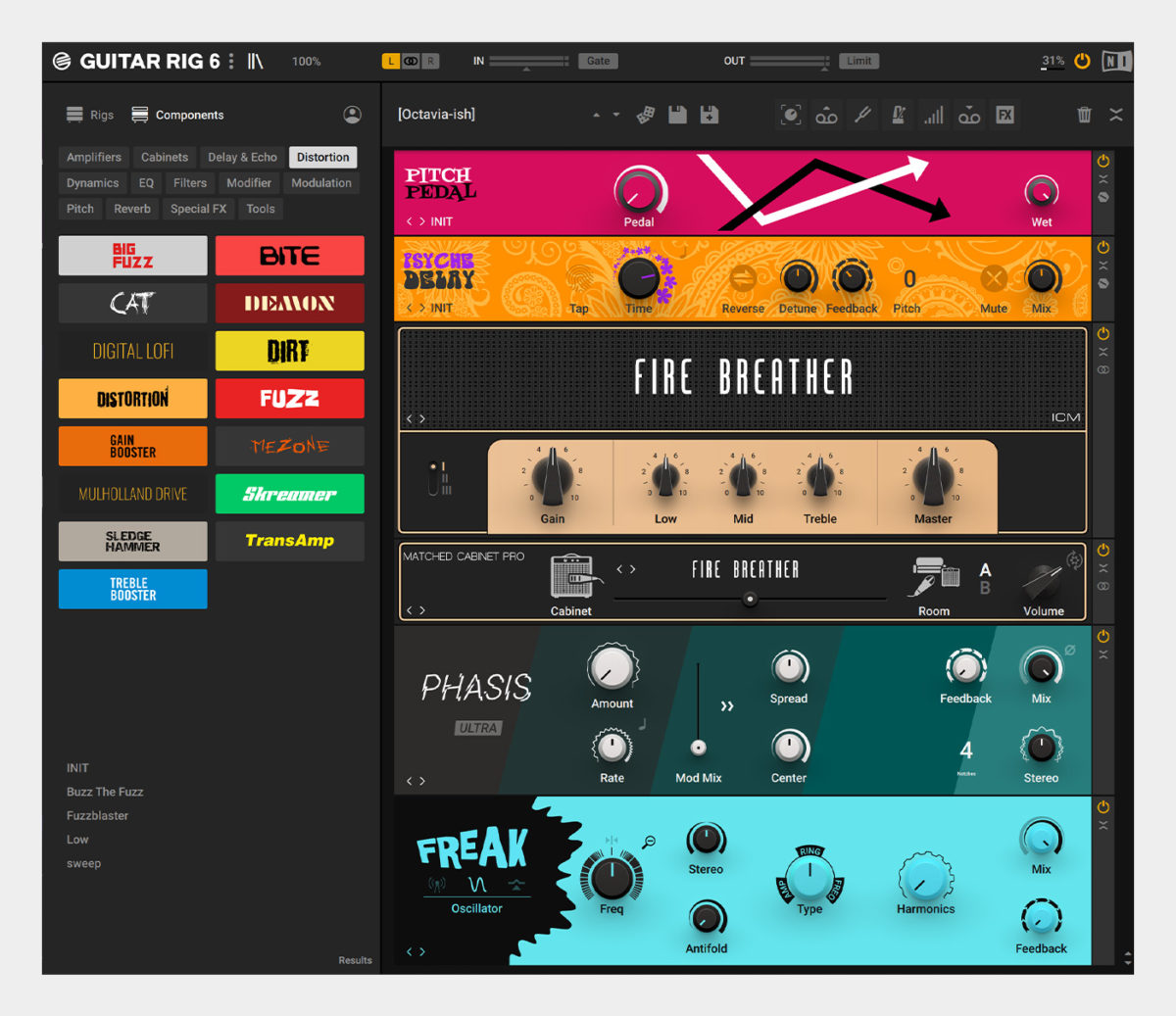

Native Instruments’ Guitar Rig 6 has a ton of different modules that will help you test out different types of analog saturation.

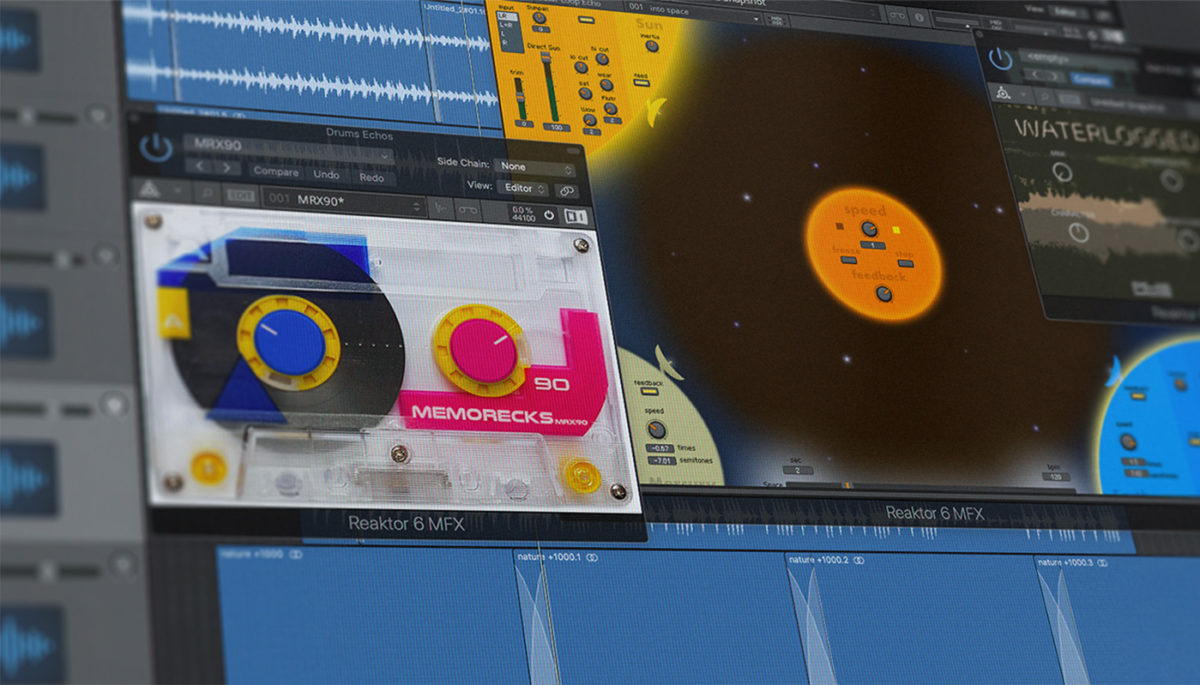

And you can grab these free Reaktor patches to get really wild with distorting and tweaking your sounds.

2 Dynamics and Gain-Staging

One of the key aspects that people associate with analog sound is a fullness and depth. This is a result of the saturation and distortion we discussed above, but another key factor is compression and gain staging.

The dynamic headroom of digital devices and analog devices are different, and this is where the concept of clipping is important. Clipping is the point at which a signal overpowers a device and results in lost signal, they are literally clipped. Analog circuits in mixers, compressors, equalizers, etc have the ability to saturate and distort before they clip. This means that they can continue to transmit signal that surges past 0 dB, and as a result, they have a greater amount of dynamic headroom. Digital devices, however, can not process signal past 0 dB, and therefore they have less dynamic headroom.

So how do we adapt a digital signal to function more like those running through analog devices? The key is to increase the dynamic headroom similar to how analog devices handle signal. By keeping your signal far away from ever touching 0 dB on your channels (and inserts), you will retain the dynamic headroom.

Another key tool to help achieve this is to use compressors and expanders to preserve dynamic range. Compressors are often accused of only reducing dynamic range, but in fact, clever use of them can increase range and headroom in a signal.

To get an idea of how analog compression and dynamics can affect your sound, try Supercharger GT.

Or check these free dynamics tools from the Reaktor library.

3 Harmonic Excitement and EQ

Harmonic excitement is very similar to what we spoke about in the saturation section, as it often results from saturation. When an audio signal is processed through analog circuits, the signal can gain harmonic multiples of it’s original tone. Let’s imagine we have a digital sine wave tone pitched to C2, which is roughly 65 Hz. Then we run that tone through an analog pre-amp. As we add more gain to that signal, we will see multiples of that original tone across the spectrum. Those multiples will appear at harmonic intervals, usually around octaves such as C3 (130 Hz), and C4 (261 Hz) and even at fifths like G3 (196 Hz) or other multiples. These multiples can make a lower tone more audible in a mix, as they extend the original signal further up into the frequency spectrum. Most circuits will add more multiples (harmonic excitement) the further they are saturated. Some circuits begin to add harmonic excitement just passively, without any extra gain or saturation added. Other circuits will add even-numbered multiples, while some circuits will give odd-numbered multiples.

Now that we know the way that analog harmonic excitement adds subtle harmonizing tones to a digital sound, we can use that to inform our EQ techniques. If we want to enhance the harmonic multiples of a tone, we can also subtract the tones that are not multiples. Let’s continue with the example of the 65 Hz tone. We want to enhance the even-numbered harmonics of that tone (2×65=130, 4×65=260,etc), and we can emphasize those by subtracting out the odd harmonics (3×65=195, 5×65=325,etc). WIthout adding any analog circuits, we’ve already enhanced the analog feel we want by reducing sounds we don’t want.

A great way to test out harmonic excitement is to use iZotope’s Exciter in Neutron 4.

Here are some free lo-fi and tape effects in Reaktor.

4 Nonlinear Variations

One area where digital sound differs from analog sound is in the ability to repeat a sound or operation identically at each instance. A digital synthesizer will create the same note in exactly the same way, every time. Similarly, an LFO on a digital filter will repeatedly oscillate at precisely the timing to which it is set, MIDI notes and sequences will do the same. Analog devices are less perfect. These imperfections in timing, duration, or other envelopes and patterns can be subtle, but they often have a subliminal effect. Our ears hear these imperfections and notice a more “natural” feeling, and those small variations are often appealing because they’re similar to how live musicians can make small, subliminal variations in how they play. This is familiar and appealing to our brains, even on an unconscious level. Classic analog sequencers like in the Roland TR-808 or TB-303 are famous for having what’s known as “drift” – their timing is not exact, and those small changes made their way into the classics of modern music.

We can use this knowledge to make our digital signal sound more analog. Music is a series of patterns. Subtle, tiny changes over any pattern can give the listener a perception that something electric is happening. Small, occasional variations in the timing of a filter, or a note in a sequence can enhance the analog feel of something. Keep in mind, a little bit goes a long way. Sometimes even when it’s too subtle to hear, the effect is there.

These subtle nonlinearities are sometimes built into newer plugins. Analog signal modeling has come a long way in the past 10 years, and plugin makers have gotten extremely adept at using your computer’s processing power to add small bits of analog flavor to your digital signal.

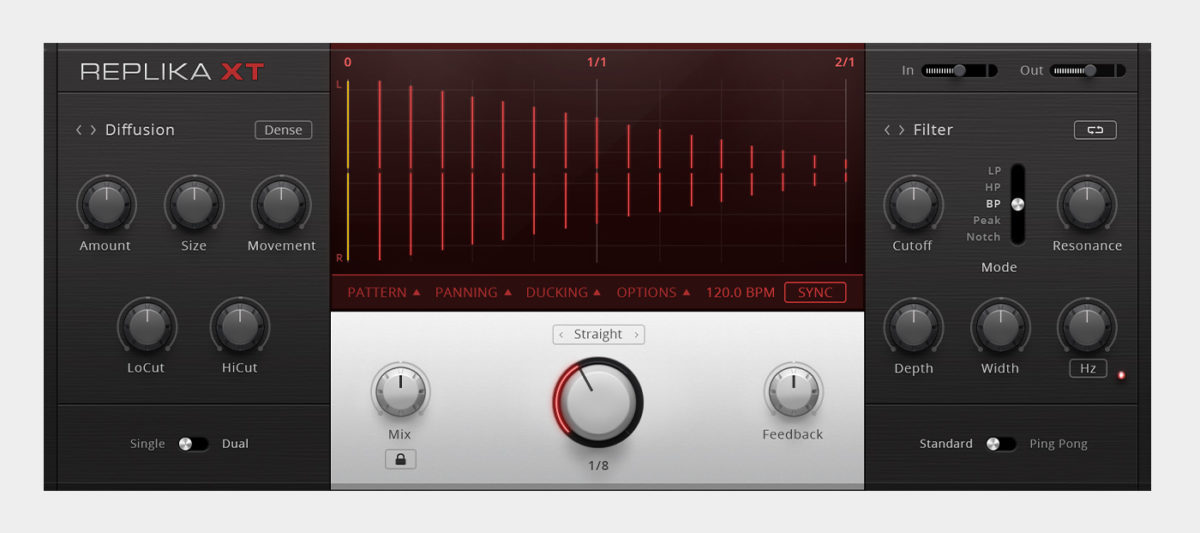

Try the “analog” feature in Native’s Replika XT delay.

You can also add some fun variations to your tracks with these free sequencer tools in Reaktor.

The most important thing to remember when trying to make your digital tracks sound more analog is to use your ears. Only you know what sounds good to you. Some analog sounds will appeal to you, some won’t. You may want your tracks to sound “lo-fi” and dirty, or you may want them to sound subtly warm and classic. There’s no “best” – there’s only what sounds right to you, and taking the time to find that is more important than any single result.