Danny Elfman’s vast career began in the early ‘80s as the singer/songwriter behind new wave band Oingo Boingo. Throughout the ‘90s, he changed course and gained worldwide recognition for his more than 100 film scores alongside work for TV, theatre, and the concert stage, encompassing long-standing creative relationships with eminent directors such as Tim Burton and Sam Raimi.

Elfman will require no further introduction for many of you, but to recap a few career highlights, we might mention Burton’s Batman, Edward Scissorhands, and The Nightmare Before Christmas; Oscar-nominated scores for Good Will Hunting and Men in Black; the first two instalments in Raimi’s Spiderman trilogy and this year’s Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. And not to forget that Simpsons theme.

Prior to the pandemic, Elfman carved out some space in his hectic scoring schedule to focus on rehearsing for a stream of live concerts, including a rare performance at Coachella. However, their cancellation forced the composer to look inwards and reroute his exasperation into his first solo album in 37 years, Big Mess. (he did eventually get to play at Coachella too – catch a glimpse of that below).

We spoke to Danny about how the ambitious project pushed him beyond his comfort zone, helping him to rediscover his voice and build a new sound palette from his KONTAKT sample library and the more recent acquisition of GUITAR RIG.

To what extent did the pandemic create the conditions for you to make your first traditional album in almost four decades?

It was a very weird configuration of events – a kind of perfect storm. I’d already decided not to take film work for 2020 because I knew that I had Coachella coming up and a lot of concerts, including two works in Europe and the Elfman/Burton stage production of The Nightmare Before Christmas. Of course, with my luck, the one year out of 37 that I decided not to take film work was the year that 22 concerts evaporated all at the same time and I found myself holed up with my wife, son and dog thinking “what am I going to do with myself?”

How did Big Mess arise from that?

I’d been rehearsing for Coachella and had one new piece of music that I was very excited about and going to premiere. It was part of an idea that I’d had a year before for a festival in Tasmania called Dark Mofo where I’d pitched them an extended concept piece for a rock or punk band with a chamber orchestra and nine female singers and modified that into a song. So Coachella unleashed a number of things – one was getting me to put my voice to something and, two, suddenly having an electric guitar at my fingers.

Lyrically, the album is quite acerbic…

I put lyrics to a song that was originally called I’m So Sorry, now just Sorry, and realised I had so much venom in me that needed to come out. The whole project was a combination of having time on my hands, annoyance over the tour cancellations and the intense frustration of being an American in 2020 and living in what I felt was an Orwellian–themed world that I could never have imagined happening in my lifetime. I opened up the door to writing songs and it ended up being like Pandora’s Box.

Although Big Mess is an electronic rock album, your film score influences live in its string arrangements. Did you always plan to make such an epic and cinematic rock album?

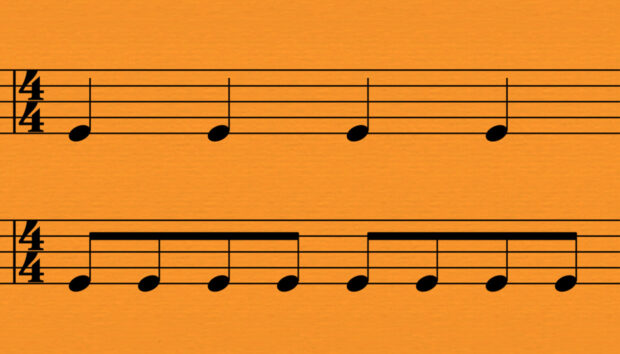

I’d had this concept in my head from the year before of using strings as a driving rhythmic force rather than an embellishment. That’s not something I hear very often, so yes I did start with that in mind and the songs Sorry and Happy defined the sonic template for the rest of the album. The fact that one was very heavy and the other very light and crazy also defined the album, because by the time I’d hit 18 songs there was almost an even split between those two styles. I remember telling my manager that maybe this should be two different albums because I had this competition going on internally and the songs were taking turns. It wasn’t something I was expecting to do and it felt very therapeutic, so the album was an unintentional surprise – like a weird gift.

You used a number of engineers to help mix the album. Is that something you’d typically do in the soundtrack world?

I‘ve mixed every piece of every soundtrack for the last 37 years, but I still need an engineer. Mixing is a very technical job, so it doesn’t really matter if it’s a rock album or a soundtrack I depend on good engineers, especially for orchestra. Back in the Oingo Boingo days we always had an engineer but I’d never used multiple engineers before – it just worked out that way because I worked very closely with the owner of Epitaph Records, Brett Gurewitz, and he was turning me on to different people. As I got deeper into the production, I realised that specific engineers excel at driving rock beat songs while others specialise in stuff that’s more textural. The third engineer I worked with had done a shit ton of punk albums and I wanted someone who had that raw aesthetic.

In the movie world you prefer to write to a cut than a script. In this case, did the lyrics inform how you visualised the album?

The lyrics tend to go side by side. I usually start with a simple riff and maybe a bit of a bassline or piece of guitar and by the time the song develops I have half fleshed out lyrics. It’s funny because I just watched the amazing Beatles documentary that Peter Jackson made called Get Back and seeing how they worked made sense to me. You go in with a melody or a tune and a feel for a lyric, or what will become the lyric, and certain words fall into that cadence. At first, you don’t understand it but at a certain point it has a sense of intent and starts to take off. It’s a symbiotic thing and of course it’s very different than writing to film, but whether I’m writing a concerto or a rock album, there’s a common drive for me to get out of my comfort zone.

I’d record guitar, chop it up in Kontakt and turn it into an instrument by putting it through different effects and treating it as if it were a sample.

What was it like stepping in front of a microphone again?

It was scary because in the last seven or eight years the only singing I’d done was as Jack Skellington for The Nightmare Before Christmas. But Jack has Jack’s voice and I no longer knew what my voice was. The first thing I learned is that I can no longer reach the high notes. I heard the British singer Tom Jones in Las Vegas when he was my age now and, my god, he was killing it. He’d hit these high notes longer than he had to just to say to the audience, oh yeah, check this shit out! But he never stopped singing and therein lays the difference. While I knew that my high range was no longer there, I discovered over the first three or four songs that I had access to a different kind of quality, and when I recorded the song True I became aware of the fact that I couldn’t have done this song 30 years ago. Then I was actually enjoying it because it was like trying out a new instrument.

Did you create a traditional band to jam out ideas to?

The band I used for Big Mess was the one I’d hoped to use for Coachella. We’d already rehearsed together and I love these guys, so when it came time to record I just called them up. I’d also created a large sample library in Kontakt. If you look at my template right now you’ll see that I’ve got a huge library of strings, brass, woodwinds and orchestral instruments, but when it comes to all of my prepared piano, percussion and weird sounds, I was definitely using a lot of my own stuff for some of the songs. I’d record guitar, chop it up in Kontakt and turn it into an instrument by putting it through different effects and treating it as if it were a sample. When it came time to record the album, even though I used two wonderful guitarists, I still kept a lot of what I would call my ‘fucked up’ samples that I didn’t feel there was any way to replace.

Did you present demos to the band in the same way that you would send a mock-up to a movie director?

There were demos to listen to and I encouraged them to put their own stamp on things because I had to record each musician one at a time due to quarantine. In the film world you have to demo everything, so I knew that I should treat my demo vocal seriously, but the fun thing was that although I have a great studio in Los Angeles I was actually quarantined in a house north of LA where all I have is a little writing room. I’ve still got my computers, so I have access to samples if I want to score, but technically all I had was one electric guitar, one acoustic guitar, a microphone and my headphones, which didn’t work. It was interesting to discover that was all I needed alongside my samples and a copy of Digital Performer to record into.

What other software was important to your recording process?

I used Guitar Rig quite a bit. If you listen to the song Insects, and to a lesser extent, True, there’s a lot of really crazy guitar effects that were all played through Guitar Rig. In fact, I did such a lot of crazy guitar shit that I’d intended to do an extended mix, so one of these days I’m going to make my own mix of Insects and you’ll hear shit tons of me working in Guitar Rig [laughs].

How do you find working with Trent Reznor on a remix for the track True?

I never would have imagined working with Trent, Blixa Bargeld in Germany, the punk band Fever 333 and Rebekah Del Rio. It all started with Trent, which was great because we’d never got together before. My bass player sent a song to him because I was too shy, he asked for more and the next thing we knew he’d sent over a ton of stuff for two tracks, True and Native Intelligence. I reconstructed Native Intelligence with my bass player using the tracks that Trent gave me and recut my own vocal to work better around his. That was wonderful because I never normally collaborate.

For the various orchestral parts on the album, did you invite string players in to perform on various tracks?

Just like I would on any score, I used synthetic strings and then replaced them with real strings. I’m not exactly sure what I was using originally, but it would have been a combination of four or five different libraries. For this album, I knew exactly what I wanted, so I recorded a session in Budapest with a large orchestra and used a string quartet in LA for the chamber strings.

Native Instruments is definitely attuned to that sense of people wanting to grab hold of and start messing with things to discover what they’re capable of.

Presumably, Sam Raimi’s Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness has been your latest major film project?

I just finished it less than a week ago. It’s had two world premieres – the first in Vienna with the Vienna Symphony and a percussion concerto with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. This was another casualty of Covid rescheduling, so going from two world premier concertos to Coachella in less than a month has been a real mind fuck, but very exciting! I’m also finishing a third commission for the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain, which is premiering this summer at the proms, and I’m working on a new show with Tim Burton for Netflix called Wednesday.

Do you still feel a sense of trepidation when working on a score?

Every time I start a project I definitely have this sense of, “What if I can’t come up with something good?” I’ve never lost that feeling and I couldn’t tell you if that’s a good or a bad thing, but I very rarely approach a project knowing exactly what I’m going to do or thinking that I’m going to kill it. I may sound like that to my directors [laughs], but inside I’m thinking, fuck, what am I going to do? So there’s always that fear of what if I lower the bucket into the well and there’s no water, but so far that’s not happened.

How does the latest sampling technology play into your role as a music producer/film composer in 2022?

Of course, every songwriter or composer hopes that the sampling technology improves and improves because we want more access to sounds and the ability to manipulate them. I don’t know if the algorithmic writing of music will affect me much because that’s still a very pure process that comes down to hands on keys and finding sounds. The pure sense of writing is very organic and hasn’t changed for me any more than it’s changed in the last 500 years, but with all this technology it’s very exciting to come up with fresh new sounds that open up new horizons.

Is discovering new sounds as exciting was it was in the ‘80s?

I did a lot of synth programming on both Big Mess and Doctor Strange. When a new synthesiser comes out, I still feel like a kid waiting for a toy to arrive, which goes all the way back to the ‘80s when I found a synthesizer at a music store in Tokyo that they were able to send to me. A friend of mine only turned me on to Guitar Rig in the past year, but as soon as I got my hands on it and started writing it became part of my compositional method. What I love about it is that I can just dive in and start learning without having to read a manual. Native Instruments is definitely attuned to that sense of people wanting to grab hold of and start messing with things to discover what they’re capable of. The more we move in that direction, the better.

Big Mess is available now via Bandcamp. To keep up with Danny’s latest projects, check out check out his website, or follow him on Instagram.

Photography: Jacob Boll