Ten years ago, almost to the day, we launched RAZOR: a REAKTOR-based additive synth that – maybe more than any NI product before or since – really did seem like “the future of sound.” A decade on, it still does. Today, its unapologetically digital signature can be heard on tracks by boundary-pushing experimentalists like Mark Fell and Jlin as well as mainstream hits by the likes of Kendrick Lamar and Dua Lipa – even Jean-Michel Jarre has found a place for it in his collection.

There’s one name in particular that remains inextricably linked to RAZOR’s legacy: that of its creator, Erik Wiegand aka Errorsmith. To celebrate this milestone, we caught up with the Berlin-based artist, producer, and programmer for a discussion on the synth’s experimental origins and some reflections on its success. And be sure to read on to the end for some tips and tricks from the man himself on how to get the most out of RAZOR – he’s even provided a selection of free presets.

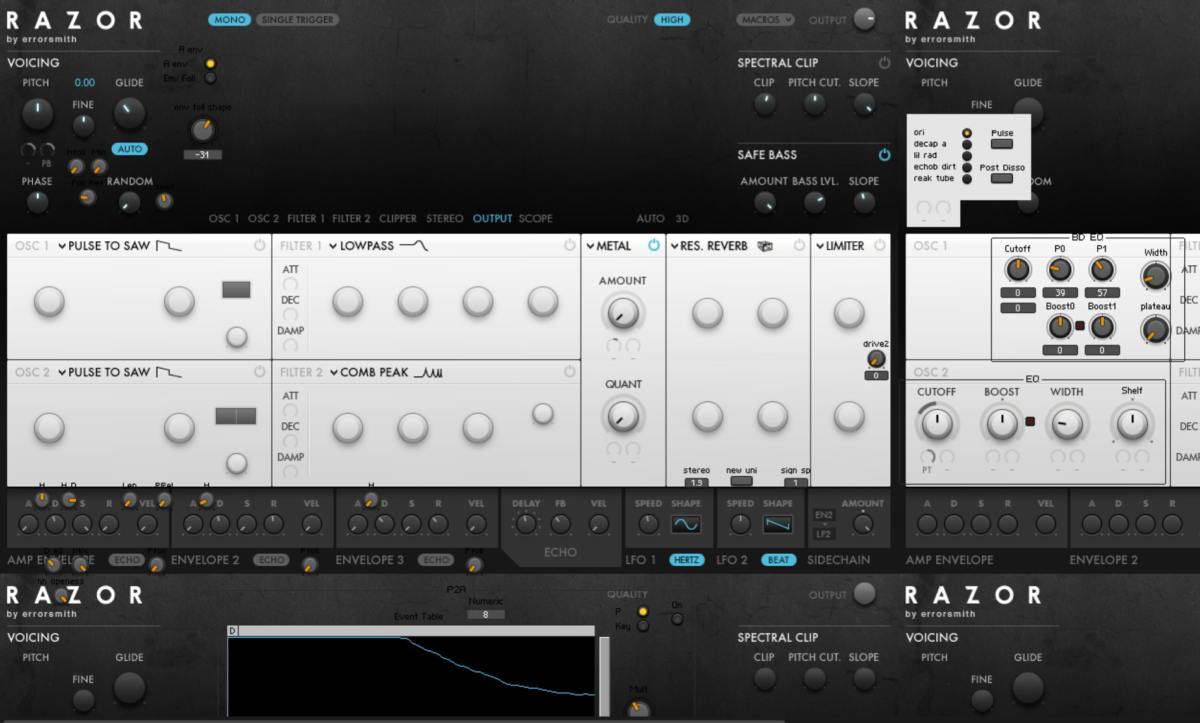

Before we dive into where RAZOR came from, it may be helpful to clear up what, exactly, it is. The name itself is a clue: it’s a sharp, precise, and unmistakably digital-sounding synthesizer, due in large part to its additive approach. Additive synthesis is, in short, the process of creating complex new sounds by stacking up partials – simple sine waves with precisely controlled frequencies and amplitudes. In contrast to more common subtractive methods used by classic analog synthesizers, additive synthesis affords the user a lot more precision with which to sculpt a sound – “a control-freak dream for a synth developer like me,” explains Erik.

“With additive, you have a great deal of control over how harmonic or dissonant a sound is. You can do something similar with more conventional techniques like ring modulation or FM, for example, but it’s kind of limited. Additive synthesis, by comparison, is like a playground in that respect. For me, personally, the dissonance effects are one of Razor’s strongest features.”

A little over a decade before starting work on RAZOR, Erik was butting up against the limitations of hardware synthesizers of the time – sometimes going so far as to crack them open and modify them to better suit his needs. But with his background in computer science, the introduction of REAKTOR’s predecessor, GENERATOR, was something of a Eureka moment. “It was a 100% match – like it was written exactly to my needs,” he explains. “It made me realize that I don’t want to code with text anymore. Reaktor’s patch-based programming is much easier for me and it helps me to try out things quickly, as you can hear the results immediately. When I started with Reaktor there was no need to modify my analog synths anymore; I could take something from the Library, learn from it and modify it – or develop my own stuff from scratch.”

1999 saw Erik debut his Errorsmith moniker with the release of Errorsmith #1, an album made entirely with his own REAKTOR patches. That same year, he joined Native Instruments’ Quality Assurance team and ultimately took on the responsibility of maintaining the REAKTOR Library itself; even after he went freelance in 2004, Erik continued to contribute to the library with each update.

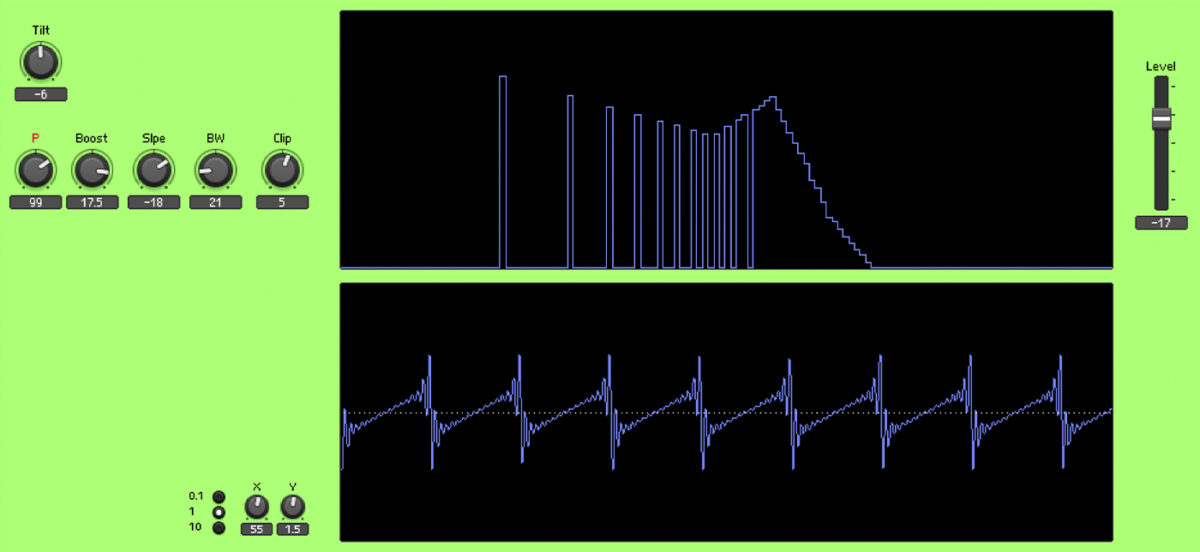

It was in 2009, having been asked for ideas for a forthcoming update, that Erik submitted the first draft of his additive masterpiece: a stripped-back, lime-green ensemble that already bore the RAZOR name and an early version of its trademark visualisations. This proof-of-concept – an additive simulation of a saw wave running through a resonant low-pass filter (present in the synth today as Lowpass Ramps) – was a simple, but unique idea.

“In the beginning there was just the idea: ‘How would it sound if I simulate a resonant filter using an additive approach?’ So I made it, added some spectral clipping, and I was already really happy about the result. It sounded different enough that it already had its own character. And then I kept going, wondering what it would sound like to simulate classic synthesizer features: different filter shapes, oscillator types, chorus effects… I realized there was a lot of potential in this simple idea. At that time, there weren’t really any additive synthesizers exploring those ideas. They were typically used to simulate other instruments – replicating the sound of a piano, things like that.”

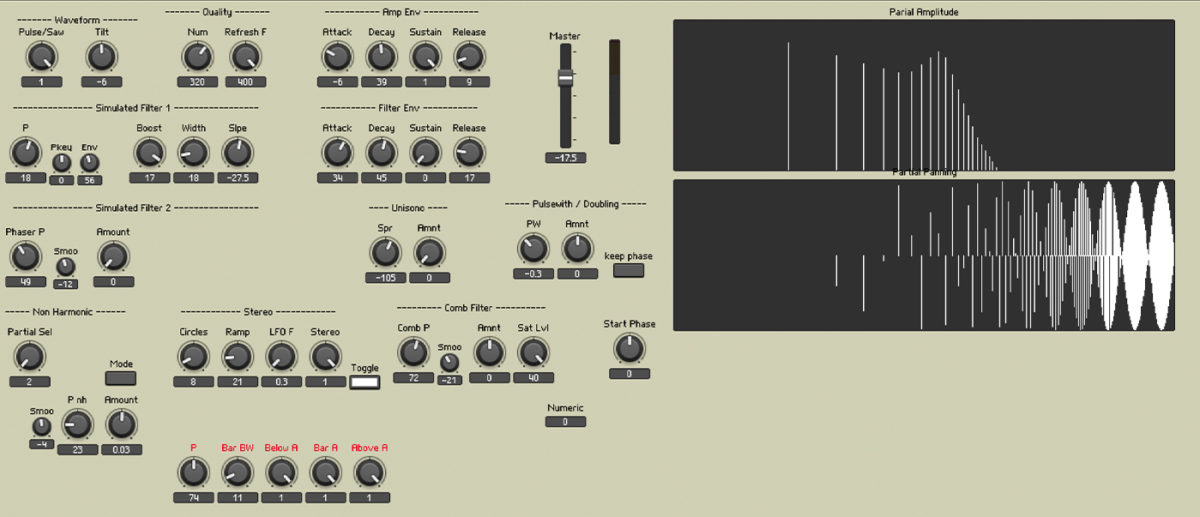

By early 2010, Erik’s RAZOR prototype had grown to include blendable waveforms, multiple filter emulations, unison and stereo effects, and a separate section for adding inharmonicity or dissonance – all created using additive techniques.

Around this time, Erik was beginning to probe the outer limits of his method, going beyond interesting takes on classic concepts to imagine new ways of manipulating sound. Take the Waterbed filter, for instance:

“That’s probably about the oddest, most outlandish idea I could think of for a filter,” he explains. “I wanted a way to demonstrate the amount of freedom I had to create a filter with a completely arbitrary shape, so why not that of water waves? And there were other examples, like the way you can morph between the comb filter and phaser-like effect. Or have barber-pole phasing, where the peaks are going continually up or continually down – for every peak or notch that disappears at one end of the spectrum, a new one is formed on the opposite side, which creates an acoustic illusion.

“My focus was on looking at what was already out there, recreating that with additive techniques, and then expanding on it. That way, when you open up RAZOR, you’ll see parameters that you’re already somewhat accustomed to, but you can use them to create something totally new.”

Following this ethos, RAZOR grew and grew. By fall of 2010, Erik delivered the first full prototype to NI (though not entirely on time, he confesses). From there, it was a case of sharpening the concept and designing an interface that would encourage people to pick up the synth and get creative with it.

The pitch was ‘complicated new synthesis presented in a traditional analog layout.’

A large part of this work, as NI Design Lead Efflam Le Bivic explains, was about simplifying the controls – or rather “hiding the complexity.”

“The pitch was ‘complicated new synthesis presented in a traditional analog layout,’” he says. “In Razor, everything except the distortion is done with operations on the partials, so it doesn’t really have stages chained one after another like an analog synth. What I did was to replicate that analog workflow visually instead, starting from the oscillators then to the filter, the reverb…

“The second task was to reduce the complexity of each ‘module’. The low-pass filter, for instance, actually has 16 knobs, but it looks like 4 because all the modulation amounts and the envelope knobs are small and minimalistic.”

To finish the interface, Efflam brought in freelance designer Philipp Granzin. “It had to be elegant, easy to use, and with a clear visual structure,” recounts Granzin. “I wanted to emphasize the hierarchy of elements and find a futuristic graphical expression that related to modern electronic music. To that effect, I combined a bright, high-contrast look with cold colors and a subtle texture that referenced the mood of decay in techno culture.”

“When I saw it for the first time I was like, ‘Wow, that looks like the most expensive synthesizer ever!’” says Erik of Philipp’s initial design. “Those were really my words to Efflam. Not that the most expensive things are necessarily the best, but this thing looked really valuable. And I’m biased, of course, but I really don’t think it has grown old.”

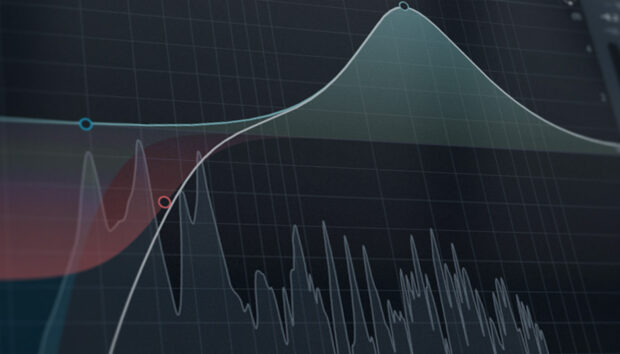

RAZOR’s most recognizable visual element was still incomplete – the prominent 3D spectral visualization at its center.

“Matt Jackson [then a conceptual product designer at NI, now with Ableton] asked me if we could have something more visual,” recalls Erik. “Almost like a screensaver. I didn’t want to do something cheesy or just for the sake of it, but I realized it didn’t have to be – it could be something useful. I wasn’t fully convinced until I had this obvious idea of doing something like Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures record cover.”

By the time the spring of 2011 rolled around, RAZOR’s final layout was re-skinned, the new 3D visualizations added, and the synth we know today was born. “It was a total eye-opener for me again when I saw the final version – the impact the right GUI can have. It wasn’t just another synthesizer, it was Razor.”

“It wasn’t like releasing a record,” Erik remembers. “Even though I see Razor as a work of art and not a mere tool, I think music-making for me is a more personal, passionate, and at times more painful engagement. So releasing my music feels different.

“Making synthesizers is part of making music for me. So it’s interconnected, but I was ultimately making something for other people to use in this case. If someone tells me to make my music easier to listen to, I’ll tell them that I didn’t ask for their opinion, but I was happy to have the feedback from NI on Razor. It was important for me that the presets were varied and not limited to my musical style – and I didn’t want to make the music for the video for the same reason.”

RAZOR 1.0 finally launched to the public in March 2011 (with a video soundtracked by NI’s Antonio de Spirt) and was met with immediately positive feedback. “Wicked,” “killer,” “bumpin’,” said a “duly humbled” Computer Music magazine at the time, and prominent artists responded with similar enthusiasm (check out a few examples on the NI website).

So what’s it like to hear your synthesizer on the radio? Despite RAZOR having since found favor with producers of almost every modern genre, Erik insists it doesn’t happen all that often. While the synth can be said to have a very distinct sound, even by today’s standards, the precise tone-tweaking on offer makes RAZOR equally suited to more “bread-and-butter” duties – adding a layer of sub-bass to other instruments, for instance.

“When I do recognize Razor in a track, I’m always happy,” Erik says. “Even if I don’t particularly like the music. It just makes me happy to hear that it helped realize that piece of music and was inspiring to its user.

“Of course, there are some artists that I do rate highly. Mark Fell, for instance. He’s used it quite a bit for making chords, and that’s not my field. I couldn’t imagine using Razor like that because I don’t really use chords in my own music, but I really like the way he does it. They’re very special: kind of thin-sounding, but in a way that suits his music perfectly. Rian Treanor, his son, has a more abrasive approach to sound design which is a little closer to what I’m doing. Le Dom is another artist I like a lot who uses Razor prominently in some of his tracks.”

Aside from being the creator of RAZOR, Erik’s also well-known for using the synth extensively in his own output – including for the entirety of his 2017 Errorsmith album Superlative Fatigue.

Given that RAZOR remains the most prominent component of Errorsmith’s sonic toolkit, does Erik see a downside to having made it so readily available to other producers?

“Sure, other people now have the possibility to sound like me. ‘I’m Interesting, Cheerful & Sociable,’ a popular track on my album, was made using the ‘Joker (Turn Ratio)’ preset as the only sound beside the drums – I even added instructions on how to use it in the preset name. I think it’s a great sound, but I haven’t heard anyone else using it before. I made it very easy to sound like me, but that didn’t happen.

“A synth doesn’t make music by itself,” he states. “You’ve still got to create something with those sounds. That’s why I’m relaxed about potentially giving away ‘my sound’ with these creations. There is always room to make my thing with it, which differs from what others will do with it. Also it helps that I know this synth better than anybody else and I can easily adapt it to my special interests and needs.”

“I never held back any ideas when I created Razor. I wanted to give it everything and show what I’m capable of doing.”

With Erik’s history of modifying synthesizers, it would be surprising if he’d gone a full decade without tinkering with RAZOR, and he has indeed been under the hood to add features over the years. His personal version has a few small tricks up its sleeve – like an added hold stage in the amp envelope, slight variations on the different filter types, and an additive EQ. But these are specific hacks for specific parts of specific tracks. Erik’s creative process, he says, mostly obliterates the line between coding synths and playing them.

“The things I’ve added over the years aren’t things that would make sense in the release version,” he insists. “One of the big strengths of Razor is how lean and uncluttered it is – how easy it is to understand what’s going on. It doesn’t make sense to start adding knobs that are only of interest for a very particular job.

“I never held back any ideas when I created Razor. I wanted to give it everything and show what I’m capable of doing.”

Ten years on, as fresh as RAZOR still sounds, it’s hard not to wonder what comes next. While Erik will “never say never,” a RAZOR 2 doesn’t appear to be in the cards – at least not imminently. “I’m very happy with how it is. There’s not much missing. To expand on it would mean to add complexity, and that’s not something I want to do.”

“When I make music today, I still use Razor,” he offers. “That’s still my mindset – it’s still additive. I think if there’s ever going to be a follow-up, it’s definitely going to be an additive thing. That’s still what’s interesting to me.”

RAZOR for beginners: Three top tips from Errorsmith

Before wrapping up, we asked Erik about some of his favorite RAZOR features, and how he uses them in his work. “I take a really minimal approach,” he says. “One thing at a time. That’s what I like about Razor; you can select one feature, add another and it’s already done. You don’t need to have two oscillators going and two filters and dissonance effects and stereo.”

So if you’re just getting to grips with RAZOR, here are three highly recommended features and a few pro tips for using them, courtesy of Errorsmith himself. Erik has also kindly provided all the presets he created for the demos below, along with their Ableton project files (for Live 9 or later) – download the pack here.

If you don’t yet have RAZOR, but are feeling inspired to check it out, you can grab the free demo here.

Pure dissonance

“I’d recommend just exploring the dissonance effects first – just go to the default preset in the Errorsmith section and you’ll get a sawtooth with a filter. Turn the filter off, go immediately to the dissonance effects and just play with them first. Some of them are so drastic that they could be the main feature of a sound by themselves – if you feel like it’s a too bright, you can turn the filter back on and take it back a little bit. That can already be a cool sound in my opinion.”

Formants, not filters

“With the formant oscillators, sometimes you don’t even need any filtering – modulating the formant frequency is enough to create a rich sound. Adding one of the stereo effects might be all that is needed. Keep it simple.”

Doubling down

“With a dissonant sound, since the partials are already inharmonic to one another, you get additional partials when you distort them. So it’s interesting to try out distortions together with the dissonance effects. For instance, a very drastic one is the Clipper – with the little razor blade icon. It’s basically a two-stage wavefolder. If you apply that to a dissonant sound, it gets very rough.”

You can keep up with the latest from Errorsmith over on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. His latest music is available to stream or buy via Bandcamp and SoundCloud.

Photos: Camille Blake