With his first studio album in 14 years released earlier this year on Skint Records, ‘The Desecration of Desire’ is a reflection of Dave Clarke’s deeper, musical tastes. It’s an electronic album, brimming with guest vocals, built upon the framework set by post-punk icons, and styled in darkened, modern production techniques. Speaking to Native Instruments, the techno-producer-DJ talks about how he records vocals, writes basslines, and makes drums, reflecting upon his studio process along the way.

The drums really stand out on this record. Was there a particular technique you used?

I would love to say I have a technique, but I don’t. I make tracks as if I was a kid doing Lego, where everything is smashed up in the corner, and then I just use those parts. I don’t have a drum library, or a favourites folder; I go through what’s available from Goldbaby, to Arturia, to Native and see what works.

The only technique I definitely do have is that I ship out my drums to external compressors. I let things talk to me; I’ll play with it; and sometimes you flow really quickly, and sometimes you don’t.

If a track really works, then I’ll step away. I learnt when I was younger that you could spend ages brainwashing yourself into thinking something was really amazing by working till two or three in the morning, and then waking up the next day with the same track in your head. And that’s not such a good thing. I don’t want to keep hearing that track, so I’ll step away – and if I come back to it and it still feels exciting, then I’ll work on it some more.

What part did you write first for the track “Is Vic There?”

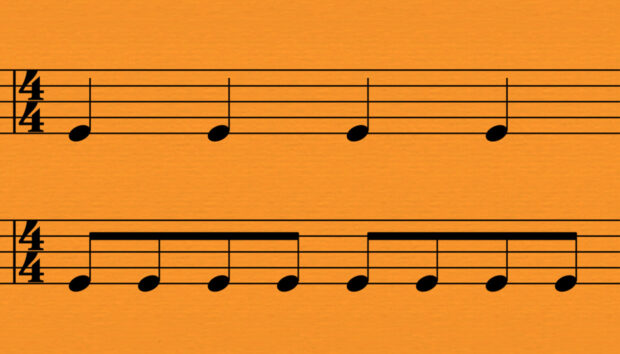

The bassline. I like the fact that it’s softly off-kilter. The bassline was working with me, and then I put the drums to it. It’s not completely quantised, so it’s more human.

And how do you approach creating a bassline like the one in that track?

I cheat a little bit. I have so many soft synths, but I’m not interested in learning each arpeggiator through each graphical user interface, so I use the Logic Arpeggiator plugin. If I have a really cool arpeggiated line, I will then copy the arpeggiator to another synthesiser. But everything is trial and error.

Once you’ve got the framework down, when do you normally bring in the vocals? And how do you get ideas and references for a suitable vocal style?

When I feel like it’s a solid idea, and I feel like I’ve made a really good track, then I just YouTube [for references]. I have a lot of YouTube channels I go to for music. With “Is Vic There?” I was listening to some old punk radio on SoundCloud, and then I was thinking about [the Department S song] “Is Vic There?”. I realised I’d forgotten about this track, and wanted to go back to it.

With Louisahhh’s vocals, I was thinking about how I could get these to go with the beat I’d written — which was a pretty chunky 80bpm beat. But it just seemed to work.

How were the vocals recorded? Did the singers just send you their tracks, or…?

I always need to record everyone’s vocals. Some people have controlled [acoustic] environments and some don’t. I would much rather have really well recorded vocals — make someone feel really comfortable. Not be a perfectionist. So the vocals are always done in three to four takes. Obviously, whoever is coming with the vocals really needs to know what to do with it. With Gazelle Twin, for instance, I said, “I want a staccato, rhythm jerk delivery,” and that’s what she came up with.

With Louisahhh, for instance, how did you process the vocals?

I don’t use autotune at all. I refuse to. If it isn’t musically perfect, I like that, as it’s more human. I put the vocals through loads of Focusrite original Red series, and through a great preamp, and brought it back into the computer. The only thing I’ll digitally manipulate is the timing sometimes, and then I’ll Strip Silence. But I’m careful with breaths. When I was younger, I didn’t like hearing people breathe on records. But now I realise that’s the humanity behind the record. If they’re a bit asthmatic, I’ll probably take the breath down by about 6db, so it’s still there.

I will move things around so they fit the timing more, and I always overlay. Then I’ll just play with it and have fun. I use a lot of Soundtoys plugins on the vocals.

Do you have a go-to plugin or effect for vocals?

I don’t have a particular thing. With things that are surgical, I would always use Brainworx bx_digital 3. They ported that to UAD as well, which makes it a lot easier. I use bx_digital version 3 for sonic precision with EQ. Sometimes the Brainworx Maag EQ4 for creating air.

For effects, I will go to Audio Damage, Soundtoys, sometimes UAD, and just enjoy being in the moment. Sometimes to be old-school, I’ll have three auxiliary buses, with chorus, reverb and special effects, which would come up on the desk as well, and I would feed maybe all the vocals of one line through that.

People really liked what I did with the vocals from Green Velvet’s “La La Land”. That was painstaking, sampling it through the Eventide Orville, Lexicon PCM 96, and Lexicon PCM 81. Painful, but fun.

I don’t bounce the audio anymore — I leave it to the very last minute because I like to have that flexibility of maybe moving the plugin chain. It’s like photography: I’d rather keep everything in TIFF [lossless image file format].

I work with templates. They’re really important to me. I keep adapting them and honing them down into a great working environment.

Was there a different approach when working with Mark Lanegan?

The thing with Mark — and this is by his own admission — is to get him in time, because he’s much more used to working with a band. So when you put someone in a heavily quantised environment, it becomes difficult. I would move his words quite a lot. Even though there is a little room noise in the microphone, I would cut that and add my own reverb, to create my own environment of how I would like it to sound.

With “Charcoal Eyes (Glass Tears)”, I wanted him to narrate it as if it was a 1930s Chicago detective novel, so I really sonically squashed his sound.

The most complex track was probably the one with Gazelle Twin, because I wanted her to ebb and flow through the beats as if they were bones, and she was the oxyhemoglobin flowing in between — but still you could hear her and have that presence. It was probably the most processed.

Did you learn something new about making music from this record?

I just felt free in doing this. It took a while to get to a point where the computer was responsive as opposed to me having to respond to a computer process. I don’t use Ableton, I use Logic — and it was at the beginning of Logic Pro X. It was a relief that everything became 64-bit. My computer became more reliable. I don’t have to fight with the computer anymore. My studio had matured.

I work with templates. They’re really important to me. I keep adapting them and honing them down into a great working environment. I use a lot of Arturia. I don’t like having synths in the real world. Everything I do with soft synths comes out and goes through a compressor and mixing desk and EQ in the real world. And that sounds analogue to me.

There’s a great synth line on the closing track “Death of Pythagoras”. How was it done?

I remember asking myself, “How do I finish off this album? It needs an outro.” Norman Cook once told me, “You’re really good at finding just one sound, and edging the shit out of that sound into a track.” I think that’s just true of my life.

And I found the sound – I put it through 15 plugins and interplayed it between the plugins on MIDI to get that sound. I call it “Death of Pythagoras” because I used to have this machine called PP10 by TL Audio, which [uses software] called Pythagoras Mastering. And eventually it died, and that’s why I call it “Death of Pythagoras”.

And the bassline on “I’m Not Afraid”?

That was Keith Tenniswood. I’ve always seen Keith as an understated sonic genius. He is the heir apparent to Gang of Four, The Stranglers. I’ve always wanted to use him to do some bass — he did some drums on the track as well. He provided me with about four different basslines, different styles, different BPM. He recorded them quite flat, and then I worked with them, and found one that I really liked — and then heavily fucked with it and processed the shit out of it. I used Waves LoAir, Brainworx bx_shredspread, and another Brainworx [guitar amp sim]. I could extenuate the slides he had on the strings, so in the end it sounds really angry.

Where from here?

I’d like to do more music. I feel quite liberated by this. You have to make the kind of music you want to make, with the first album, I wanted to make Detroit-, Chicago-influenced music. That was really me at the time. The second album, I wanted to make more song-based stuff, and now I finally felt like I have the studio and the technology is there — and I’ve got comfortable with it.